Whistler Blackcomb ski patrol is a big operation for a big resort, with hundreds of patrollers across both mountains—and eight canine patrollers, too.

Trained from puppyhood and paired with a handler for life, Whistler Blackcomb’s avalanche rescue dogs are tasked with making sure there are no humans buried under the snow anytime there’s an avalanche either in or out of bounds around the resort.

It’s a serious job, and while Pique got to chat with some of the team, Eva, an eight-year-old black Lab, wanted to get on with it, and had a lot to say.

Her owner and handler, ski patroller Matt O’Rourke, says she has always been a keener.

“She validated this year for the seventh time,” he says. “Validation” refers to passing the Canadian Avalanche Rescue Dog Association (CARDA) courses every dog and their handler needs to clear at regular intervals through their career on the slopes.

“She validated for the first time quite young—she was only 20 months old,” says O’Rourke.

“With how much drive she had, there were issues with validating that young—she was really good at searching and not so good at listening, but she’s gotten better with age,” he jokes.

The dogs usually work eight to 10 seasons as an avalanche rescue dog—granted they pass their tests every year—so Eva has a few more years to go.

BUILDING A BOND

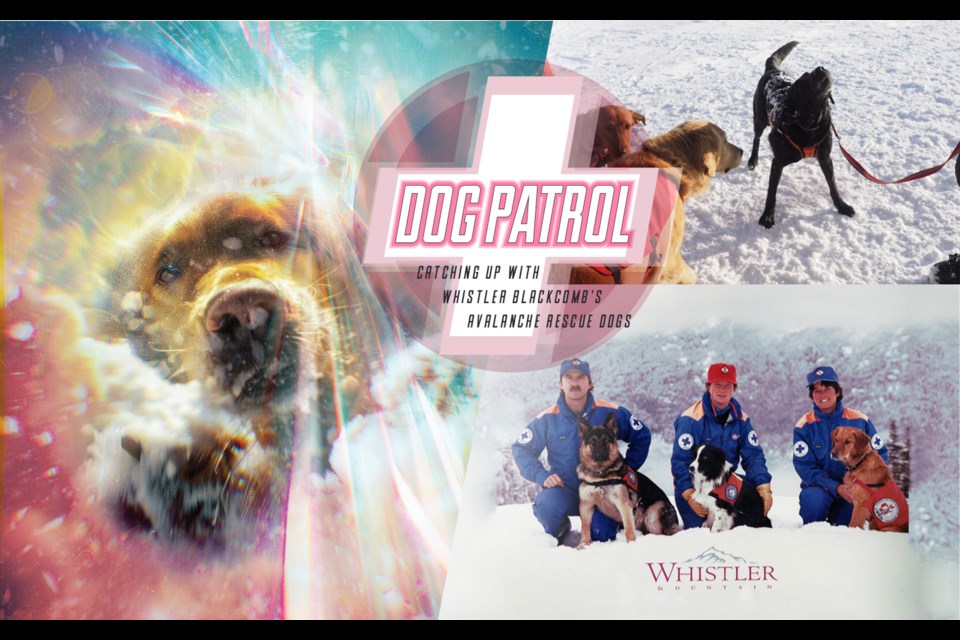

Whistler Blackcomb’s avalanche rescue dog rotation is long-standing, having been established way back in the ’80s, with new dogs coming on almost every year to replace those that retire to live with their owners as pets.

The newest recruit is Milhouse, a six-month-old, fox-red Labrador.

She is pretty keen to just play around—which her handler Jimi Martin says is all part of the training early on.

“Right now, in the puppy phase, training consists of a lot of play,” he says.

“A lot of it is about building the bond between the two of us.”

CARDA and the Whistler Blackcomb avalanche rescue dog program are not new, which means there is a lot of knowledge and experience to download as Milhouse gets older.

“There’s a lot of information you don’t know, and it’s released to you at an appropriate time to keep people from getting too far ahead of themselves,” Martin says. “So I get told to just keep focusing on playing, and every week we do a small gradual introduction to the idea of searching for people in the snow.”

For now, that consists of having someone hold on to Milhouse while Martin tries to hide with her favourite toy.

Milhouse will get a chance to validate as a CARDA-certified avalanche rescue dog when she’s closer to two years old, but in the lead-up to then, training will become gradually more intense.

Small steps for now, though.

“A lot of it is exposure,” Martin says.

“We spent two months just playing around and climbing on the snowmobiles, starting them up and turning them off. Now we’ll ride the snowmobiles. Same with the chairlift, just hopping on and off when it’s stopped, and now we’ll ride the Peak Chair.”

Martin, who has spent seven seasons at Whistler Blackcomb, says he has wanted a dog for a long time, and after four years of applying to enter the avalanche rescue dog program, he finally got an in (and a dog).

“I was interested in this because my uncle was a dog handler back in the ’80s through the early 2000s,” he says. “He validated his first dog the year I was born … When I moved out West I got to know him a lot more and do a lot of the stuff he did, and learn about it, and it always piqued my interest, and seeing the dogs at work was super cool.”

‘IT’S SHOCKING HOW INTELLIGENT THEY ARE’

Throughout the chat with the patrollers and their canine colleagues, Jasper, an eight-and-a-half-year-old golden retriever, obediently sits by his human, Kevin Tennock.

The obedience is the result of thousands of hours of training over years—from simple things like getting used to having so many people around, to more complex things (for a dog) like hopping on a chairlift—and that’s not even getting into the CARDA certification.

Tennock says his desire to become an avalanche rescue dog handler came from a previous career.

“It comes from when I used to work for Air Canada as a customer service agent and worked in the customs hall,” he says.

“They had drug dogs there, and I got to know the dog handlers, and I just found it amazing what they could sniff out in the airport. Then from there, when I started working here and found out about the avalanche rescue dogs, I decided I had to do that. I got into it as soon as a position became available.”

Tennock describes the job as rewarding, being another part of the team keeping skiers safe, getting them out of danger, or making sure nobody is hurt.

“A lot of times we’ll go to a site and it’s just a relief knowing where we head out there and we can clear a site and say positively, we don’t think there’s a human buried,” he says.

On arriving at an avalanche site, a dog’s job is to scope out the site (after it is deemed safe to operate on) and patrol back and forth across the slope, checking for the smell of any humans below.

(Remember the training by running and hiding with a favourite toy? Same idea.)

“It’s always amazing what these dogs can do,” says Tennock. “To this day I’ve never been more amazed every time we go out. It’s shocking how intelligent they are.”

Both Jasper and Eva went through the CARDA program together, so they’re almost like siblings on the mountain—but the closest connection is that between dog and human.

“Bonding—it’s huge. These dogs are 100 per cent our dog,” says Tennock about Jasper. “They will listen to us more than anyone in the world, they’re totally focused on us. You wouldn’t think you can have that kind of connection with anything or anyone, but it’s definitely there.

“One of our older handlers once said he spends more time with his dog than he does with his family, and it’s true, because they’re at home and then they’re at work—they’re with us 24/7.”

O’Rourke shares a similar sentiment.

“I get to bring my best friend to work, which is pretty rad,” he says.

All three patrollers Pique spoke with are first-time dog handlers, and they all said they love it.

“Watching them do what they do is kind of miraculous,” says O’Rourke. “The first time they validate, there’s definitely this huge pride that they can do this.”

O’Rourke notes there was less training with Eva as she got older—but that was because she was dialled in.

“We were out the other day on an avalanche response, and they’re straight into it,” he says. “They know exactly what they need to do, they get the game.”

On that, O’Rourke says Eva is locked in to the work, and pretty good at ignoring guests even if she draws their attention by being a dog.

“She just ignores guests unless I’m specific. I can get her to engage with someone, but she definitely doesn’t run up to guests or chase after guests, they’re so focused. And that comes from years of getting them to ignore humans,” he says.

“At work, it’s her and I, it’s our time … up here she just wants to work, she wants to engage. Standing around like this, she’s like, ‘what are we doing?’”

Pique can confirm Eva didn’t want to stick around for an interview.

HISTORY STARTS AT WHISTLER

The story of avalanche dogs in the resort didn’t start recently, and in fact, CARDA has its roots in Whistler, having been “inspired” (if that’s the right word) by an avalanche that caught a patroller who had the know-how, and the foresight, to think there was an extra something to be done for safety on the mountain.

That patroller was Bruce Watt—he survived the experience and was encouraged to pursue an avalanche dog rescue training program back in 1978—and pursue it he did.

There were avalanche rescue dogs at the time, but their handlers were with the RCMP, which to this day continues to have oversight of the “validation” and training process for avalanche dogs.

Through consultation, the CARDA program was eventually launched in 1982 by ski-patrol volunteers, and worked to help ski patrollers train dogs through a rigorous program with input over the years from the RCMP, Parks Canada, search and rescue, and more.

The training manual has been fine-tuned over the years, with the first live recovery by a CARDA-certified dog in 2000, at Fernie Alpine Resort.

Between them, Whistler and Blackcomb mountains have had 29 different handlers since the beginning of the program, with handlers often having more than one dog over the course of their careers. The current avalanche dog coordinator, Yvonne Thornton, has trained five dogs, while fellow Whistler patroller, Anton Horvath (who currently works as a CARDA instructor), has trained four dogs locally.

Whistler Blackcomb’s senior avalanche forecaster, Tim Haggerty, explained the team works to ensure there is coverage every day the mountain is open—both inside and outside the patrolled boundary.

“We can have up to 12 dog teams in the system,” he said. “At this time we have six validated dog teams, one team in training and one puppy team.”

Validation is no small task—a dog has to do two-and-a-half years of training and four CARDA courses, and then stay validated through in-person courses every two years with an annual check-in from RCMP police dog services and a CARDA validator.

ANOTHER LAYER OF INSURANCE

The rookie, Milhouse, needs to focus on her training—and even if that training looks a lot like playing, it’s still training nonetheless, so Martin will spend time and effort making sure she bonds with him, and guests don’t pat her while she’s at work (hence the harness saying “do not pet”).

Of Eva and Jasper, neither has had to locate or help dig out a trapped skier or snowboarder on the slopes.

“That’s the good news story,” says Tennock.

“A lot of sites we end up going to, it’s to clear the site, an unwitnessed avalanche, and we go in there and we can positively confirm that there’s nobody buried at the site.”

Luckily, most folks who ski in the backcountry wear transceivers and travel in groups, so ski patrollers or search and rescue can find them quickly; an avalanche rescue dog’s job is really another layer of insurance.

Every day on the mountain, ski patrol have a dog-handling team ready to respond, so there’s always a dog on the mountain ready to jump into action.

“Whether it’s in the backcountry or in-bounds, we respond as a team,” says Tennock.

Thornton’s current pup, Dyna (a Labrador), is validated in avalanche, wilderness searching and RCMP Level 1 tracking—making her integral to the program.

“Without people like Yvonne around, this program would be a lot harder to educate all of us,” says Tennock. “It’s not just our dogs that need training, we need training too.”

Want to support the local program? You can’t pet the dogs, but you can buy a buff from the team, with all funds going to the program.

They’re $25, and you can buy them from the ski patrol hut at the top of the Peak Chair.