Watching the snowline creep down the mountain in the fall used to mean only one thing: ski season is on its way! But after more than 23 years in Pemberton, I know that a descending snowline means we have entered the short, annual period of increased flood risk.

In Pemberton, the level of risk depends on multiple weather variables and their interactions between the depth and extent of snow, amount of rain forecast, and freezing levels. The term “atmospheric river” has moved from meteorological lingo to become part of the general lexicon following the floods of 2021 that caused widespread destruction to properties, significant damage to transportation infrastructure and resulted in the loss of lives.

These events mostly occur in the fall and originate in the Southern Pacific Ocean and are also known as the Pineapple Express. It is these weather systems that create our greatest risk in the fall, especially with early snowfall. More than a metre of snow will act as a sponge, soaking up late fall rain even when freezing levels spike above 2,000 m, while less than a metre can quickly melt with warm, high-elevation rainfall, drastically increasing the amount of runoff into the valley bottom rivers.

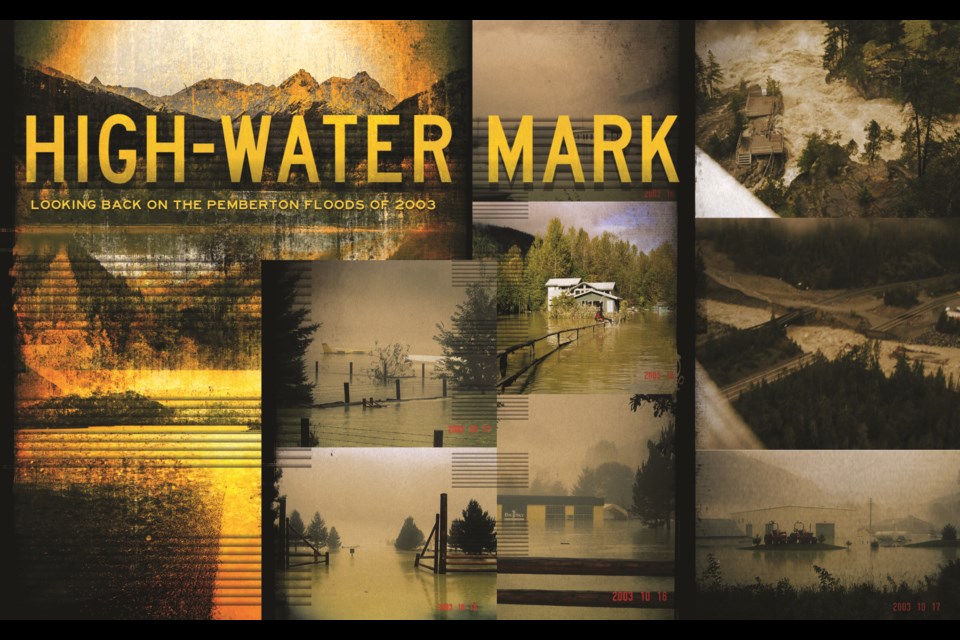

Twenty years ago, we experienced one of the most significant atmospheric rivers to affect our region in recorded history. It was significant enough it prompted Environment Canada meteorologist David Jones to joke it was more like a tropical punch. The 10 days leading up to this storm were also wet, with nearly 75 millimetres of rain that came with a good dusting of early season snowfall. Over the span of five days, from Oct. 15 to 20, 2003, Whistler received 230 mm of rain, Squamish more than 450 mm, while the gauges in Pemberton were forced offline, drowned out halfway through the storm.

Jones was astounded at the magnitude of the event, saying “the quantity of rain has more or less stunned us.” This storm resulted in the highest flows recorded on most gauged rivers in the Sea to Sky, including the Squamish River and Lillooet River in Pemberton.

This was the first flood I had ever experienced, and while it was extremely unnerving, it was also exhilarating in the way natural disasters can be, despite the very real danger they pose. Many of the longtime Pemberton locals seemed unfazed at the rainfall forecasts, as flooding is a cyclical part of the landscape, with some of the largest floods occurring in 1940, 1984, and 1991. I was told that farmers prepared by tying canoes to the porch to be ready for when the Ryan River meets the Lillooet River across the upper valley fields.

TURBULENT FORCES

Just prior to the flood, I parked an Isuzu Trooper in the commuter parking lot next to the Pemberton Information Centre and listed it for sale. It belonged to a friend in Vancouver who thought they may have more luck selling it here. On the rainy evening of Oct. 17, 2003, I attended the Whistler Naturalists’ annual Fungus Among Us festival for the Friday evening talks. After a post-session beer at Citta’s, I headed home around 11 p.m., navigating the deluge with a friend. It was impossible to see, even running the wipers at full, with rainfall amounts estimated at the time to be an astounding 10 to 20 mm/hour.

The Rutherford Creek Bridge would still hold for approximately four more hours before succumbing to the turbulent forces of the storm that eroded the abutments, ultimately causing the decking to wash away. In an incredible story of survival, while returning to Pemberton following a shift at Moe Joe’s, Casey Burnette escaped with his life when the vehicle he was travelling in careened over the now gaping maw of the torrent, while his brother Jamie Burnette and Ed Elliot were sorrowfully never found. Tragically, Darryl Stevenson and Michael Benoit were also killed in similar fashion, unable to see the chasm left behind by the failed bridge in the downpour.

The rain was unbelievable and prompted 20-something me to gather some friends at midnight to wander the neighbourhood to check out the situation. I was living in the Glen at the time, and we tried to make our way to the trail along the Arn Canal but realized water was lapping at the end of Olive Street. By this time, the Monte Vale townhomes were starting to flood. By daylight, excavators and dump trucks were working frantically to increase the height of the bank to keep the Arn Canal from flooding more homes. We knew by 6 a.m. that the bridge was out and I would not be heading to Whistler for the mushroom walk. That morning’s tour brought us up the Pemberton Meadows Road before we were stopped at the Riverlands barn where the Ryan River blanketed the road. By this time, all access points in and out of Pemberton joined the fate of the Rutherford Bridge, including washouts along the Lillooet River Forest Service Road at Mowich Creek and Highway 99 at Pasture Creek through Mount Currie.

By very early Sunday morning, it was still pouring while I sat in my doorway watching the moat that surrounded my house deepen. Listening to Mountain FM, the announcer proclaimed the rain had finally stopped in Squamish. I wanted to call him and frantically tell him it had not stopped in Pemberton, and I needed more accurate information now! The rain did stop that morning, but constantly marking and remarking the water levels while watching levels rise is likely a familiar exercise for anyone that’s been affected by floodwater. You are constantly calculating and recalculating next steps in preparation.

ASSESSING THE DAMAGE

Road repairs began in earnest, and when the Pasture Creek washout was reconstrucuted we headed to Lillooet Lake to assess the damage. At this point, there was little to do, as the road to Whistler and our jobs wouldn’t be fixed for at least a week. Lillooet Lake is key to capturing and storing flood water, though once it reaches capacity there are real problems upstream. Lillooet Lake had reached capacity in 2003 by Friday, creating a backwater effect for kilometres upstream. This is most critical for properties in Mount Currie, where the heightened risk is based on blatant disparity in flood protection investments that completely omitted protections for the Líl’wat Nation.

One of the most astounding things to see was the amount of wood in the lake. It formed a solid blanket from the river confluence all the way to Strawberry Point, approximately six km downstream. The floating debris was peppered with North Arm Farm pumpkins, coolers, freezers, and other floating yard detritus.

We all gathered around early in the week to watch the giant helicopter land near the Highway 99 intersection to deliver bread and milk following a rush to clean the shelves at the local grocery stores. At that time, we noticed the Isuzu was missing, but thought it might have been towed to prepare for flood response. We ultimately reported it stolen, and I received a call a year and a half later that it had been found. As reported by Alison Taylor of Pique Newsmagazine in 2013, Robert Micheal Leibel (35 years old) had been working at the Pioneer Gas Station for about three weeks, was unhappy with his move to Pemberton and was hoping to return to his girlfriend and children in Prince George. With ill-fated timing, Leibel stole about $1,000, a carton of cigarettes, and some lottery tickets in the early morning hours of Oct. 18, locked up the gas station with an apology note, and stole the Isuzu. He was found in the flattened vehicle buried in Rutherford Creek in December 2004, wearing his Shell Gas uniform, surrounded by the stolen items.

HOW WE GOT TO WHERE WE ARE TODAY

There were two very large floods in the 1940’s that spurred the federal government to invest in considerable flood protection works in the region through the Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Administration (PFRA). This investment resulted in massive instream construction not only in Pemberton but throughout the Fraser Valley, including Sumas Prairie. In Pemberton, the work rerouted and straightened 14 km of valley bottom rivers to drain water and allow for farming. The river straightening was reinforced with 38 km of dikes built to the standard of the time, primarily right along the riverbank.

Lillooet Lake was lowered by approximately 2.5 m by blasting the outlet at the downstream narrows and removing almost 475,000 cubic metres of material. This massive excavation and lake lowering made the Lillooet River delta one of the fastest-growing deltas in North America for half a century. The scale of these projects is unthinkable in today’s regulatory world, where no amount of mitigation or compensation would protect aquatic habitat for the multiple salmon species that rely on the watershed. And again, with all these works to protect Pemberton, there was no flood protection constructed anywhere on reserve to protect Líl’wat Nation lands.

DISCONTINUITY

Around the time of the 2003 flood, the Lillooet River had begun to reach a kind of equilibrium, where decades of river scour began to stabilize. The watershed is a dynamic place, where sand and gravel (i.e., sediment) are mobilized throughout the system by summer snow melt and fall storms. This movement of material can be amplified by development, industrial activities, and natural events like forest fires and debris flows. The rivers are powerful and are capable of wielding unbelievable force that can move boulders and bridges. Where the rivers are steep, the water flow is fast, and sediment moves quickly. As the river flattens, the streamflow slows and the mobilized sediments are dropped, resting on sandbars, and raising up the river bottom. In the Lillooet River, the flattening and deposition begins where everyone lives. With the ongoing deposition, in order to keep the flood protection working for those that live around the river, dikes need to be raised or the sediment must be removed.

To appropriately manage the flood protection investments, the Pemberton Valley Dyking District (PVDD) was formed in 1947. As a legislated Improvement District, it is authorized to collect taxes to fund ongoing maintenance of the required infrastructure throughout the Pemberton Valley. This is a role that has become increasingly complex over time. Gone are the days where the excavator is the first tool of choice to maintain drainage ditches and riverbanks, replaced with expensive consultants hired to navigate the required permitting and complex infrastructure design. And this is a good thing—we absolutely need more environmental protections, standardized assessment methods, and support for increasing disaster resilience for the increasing risk coming our way from a changing climate.

But we are at a period in time that the futurist Alex Steffan terms “discontinuity”—where past experiences can no longer adequately predict what might be experienced in the future. This makes regulating risk challenging for all levels of government that can be as under-resourced as the rest of the private world. This has resulted in reliance on professional associations to support policy building. And from this we now have excellent standards for environmental and structural components, but these are next to impossible to logistically or financially achieve when working to build up infrastructure from the 1940s. And starting to discuss moving people off the flood plain is not a conversation most are willing to entertain, even if there was financial incentive to accelerate it.

The flood risk in Pemberton has always been real, but it has been recently amplified. In August 2010, the largest landslide in Canadian history occurred in the Capricorn Creek drainage on the side of Mount Meager (known as Qwe’lqwe’lústen in the Líl’wat’s language). The landslide deposited 50 million cubic metres of sediment into the Lillooet River valley. The Lillooet River is a powerful force, moving what experts have estimated to be, at minimum, 180,000 cubic metres of sediment per year. That equates to an astounding 20,000 dump trucks dumping sand and gravel into the river every year, or about 54 trucks per day. This represents a four-fold increase over pre-slide estimates. This deposition is a serious problem for flood managers; as the sediment settles on the river bottom in the populated reaches, it pushes the water up and over the banks.

CURRENT RISK ESTIMATES

Which brings us to current-day flood-risk estimates. In 2003, the flood flow was considered to be a 1:200 year flow. This measure relates to the probability (0.5 per cent) that a flood of that size will occur in any given year. The 1:200 year flood flow is the gold standard for what flood infrastructure should be built to withstand. With the updated floodplain mapping completed in 2018 following the landslide, the 2003 flow has been recalculated as a 1:50 year flood, or the size of a flood that has a two-per-cent chance of occurring in any given year.

The two most recent flood events occurred in 2016 and 2021. The 2016 flood was caused by a November atmospheric river that inundated properties along the lake road in Mount Currie and properties south of Highway 99 near North Arm Farm. In 2021, a heat dome caused rapid snowmelt that again resulted in flooding along the lake road in Mount Currie and evacuations along Airport Road and the Peaks and Pioneer townhomes in Pemberton. Both of those floods were categorized as a ~1:5 year event, or a flood that has a 20-per-cent chance of occurring in any given year.

All of these categorizations lead to one thing: the risk is increasing, meaning that even during less intense rainfall events, there is a greater potential for flooding. This is especially challenging for flood managers working diligently to increase flood protection using a wide range of solutions to protect the most vulnerable properties in Pemberton and Mount Currie. But the regulatory landscape is vastly different now than in the 1940s. Flood infrastructure is incredibly expensive to build to today’s standards, and in many cases, completely unachievable based on land constraints, cost, and logistical challenges with little opportunity for locally tailored solutions.

The BC Government is working on an updated flood management strategy and has just introduced a new Emergency and Disaster Management Act. There is recognition that risks need to be managed differently by rightsholders, decision-makers, supporting agencies, and all of us in the community, yet this is still a work in progress. Although 2003 was an extraordinary rainfall event, the past few years have taught us that we are moving into an unknown future, and understanding and preparing for it is all our responsibility.