For four decades now, the Xet’òlacw Community School in Mount Currie has held its annual salmon barbecue. This year, the feast was hosted on Sept. 15, an important opportunity to not only gather as a community but to honour the salmon for giving up its life.

“It’s a ceremony that honours the salmon for their return. We are people of the rivers. Salmon is our staple food. What we are teaching the children is that you are always protecting the next generation. We have to be thankful to the salmon for giving its life,” says Xet’òlacw principal Rosa Andrew.

Making sure future generations will be cared for is part of Andrew’s life work and mission.

“We have to be thinking of the generations that are yet to come,” she says. “One of our protocols is to only take what you need, never take more than you need. We always remember that the salmon has to replenish itself to return four or five years later for the next generation.”

Having an elder present at the ceremonies is incredibly important. “Through the ceremony, we bring in an elder to come and talk. Spirituality is not a religion for us,” Andrew says. “It’s something we live. When we do the ceremony, it’s important for the children that we have that spiritual connection to all of creation. We need this to honour not just ourselves, but everything around us.”

The Lil’wat Nation’s traditional territory encompasses 781,131 hectares of “beautiful, resource-rich land that includes temperate coastal regions, old growth rainforest and arid areas,” according to the Nation’s website. Lil’wat Nation traditional territory extends south to Rubble Creek, north to Gates Lake, east to the Upper Stein Valley, and west to the coastal inlets of the Pacific Ocean.

Canada’s Indian Act was first introduced in 1876—a collection of colonial dictates with the overarching goal of eliminating First Nations culture in favour of assimilation to more Euro-centric Canadian values.

Under the Act, a reserve is defined as a “tract of land, the legal title to which is vested in His Majesty, that has been set apart by His Majesty for the use and benefit of a band.”

According to the Government of Canada, the Lil’wat currently oversees 10 reserves, covering roughly 2,700 hectares—mostly situated around the Mount Currie area.

The Lil’wat is one of 78 B.C. First Nations that have chosen not to participate in the BC Treaty Commission process.

“We have never given or sold any of our land to any government or nation. Although settlers and colonial governments marginalized us from the land, we never relinquished our right to our home,” reads an excerpt from the Lil’wat Nation Fact Book published in 2007.

“As we fought to restore and preserve our rights, we earned a reputation for political protest and resistance. In 1911, the Lil’wat people joined other First Nations to sign the Lillooet Declaration. This document outlined the demands for the reinstatement of our right to our traditional lands.”

Making sure the kids learn their own language, culture and identity is paramount for Andrew and her staff.

“We are people of the land. We want the kids to learn that a part of our protocol is to be stewards, caretakers of the land,” she says. “The idea we have in this school is that we are trying to undo what Canada has done to us. Canada has confined us to reservations.”

A natural education

On Aug. 23, the Lil’wat and N’Quatqua First Nations made a surprise announcement, saying they were “shutting down” access to the popular Joffre Lakes provincial park.

In a joint statement, the Nations said they made the decision to shut down the park so they can harvest and gather resources within the territories, known as Pipi7iyekw.

“While successes have been gained through our partnership in terms of implementing a cap on the number of visitors and a Day-use pass permit, access to the resources by Líl’wat and N’Quatqua has not been prioritized,” the Nations said in a follow-up statement.

The two First Nations also said their goals have been on hold for many years and were left “overshadowed by importance placed on tourism” at Pipi7iyekw—Joffre Lakes Park.

The surging popularity at Joffre has made its share of headlines in recent years. The park accommodates up to about 200,000 visitors per year, with 1,053 day-use passes available every day.

So some might be surprised to learn that many younger members of the Lil’wat Nation have never seen Joffre for themselves.

That changed during the recent Joffre closure, when some students from Xet’òlacw got to visit the park for the first time.

“We are teaching the children that they don’t have to stay on reservation,” says Andrew. “We are the rightful owners to this traditional territory. All of our chiefs signed a declaration in May 1911 saying we never ceded, surrendered or gave up our rights to our traditional territory. Now, we are taking the kids off the reserve and onto our traditional territory. We are letting them know that we have a right to our culture. We have a right to our identity.”

The children’s rain boots are stacked up in the corner of their classroom. Any chance to get out on the land is immediately snatched up, an essential part of the education provided at Xet’òlacw. After a recent visit to the park, Charlotte Jacklein’s Grade 8 class understood why Joffre Lakes is such a hit with tourists. They all had time to explore the area on their own and reflect on its importance during their “solo.”

Ashton said visiting the lakes while they were quiet was very important to him. “I loved when nobody was at Joffre Lakes because it was clean,” he tells Pique. “It is beautiful.”

Nash was worried about the effect tourists have had on the wildlife that call the park home.

“I like Joffre Lakes because it’s colourful and beautiful,” he says. “When you go there the birds land on you because they are so used to tourists feeding them. They might forget how to feed themselves. I like it when it’s quiet. When it’s busy, there’s a lot of garbage.”

Hallie enjoyed making an ísken, a traditional winter home with her friends. Meanwhile, feeling a connection to animals and a sense of independence was what stood out for Ray-anne.

“I love the outdoors because of the animals. I have made fires all by myself and found toads,” she says. “I went to Joffre Lakes and saw the cool lakes.”

Andrew feels things need to desperately change as the country gets set to commemorate its third National Truth and Reconciliation Day on Sept. 30.

“It was the parents who had the courage to say: ‘You will not hurt our children anymore,’” she says. “Our children will not be ashamed to speak our language. Our children will not be ashamed to practise our culture or our spirituality. We are teaching them that they are the rightful owners. The problem is that Canada does not want to accept that we are the rightful owners. We never ceded. We never surrendered. Canada still sees itself as a power over who we are as a people.

“Canada still thinks that I am a Canadian citizen because they gave me this status card with a number on it. I am not. I am so connected to the land, and that’s what I’m teaching the children here.”

Xet’òlacw has a prime role to play in undoing intergenerational trauma—but it can’t do all the heavy lifting on its own.

“It is a safe space for the kids to learn,” Andrew says. “We are teaching the kids here in school, but Canada has to do its part by undoing the genocide that they have done to our people and to decolonize. I think the problem that Canada is having is that if they acknowledge that we are unceded, unsurrendered, then that takes away Canada’s baseline.”

Canada’s residential school system famously had the overarching goal of killing “the Indian in the child”—which has understandably led to a deep mistrust among First Nation parents, even today.

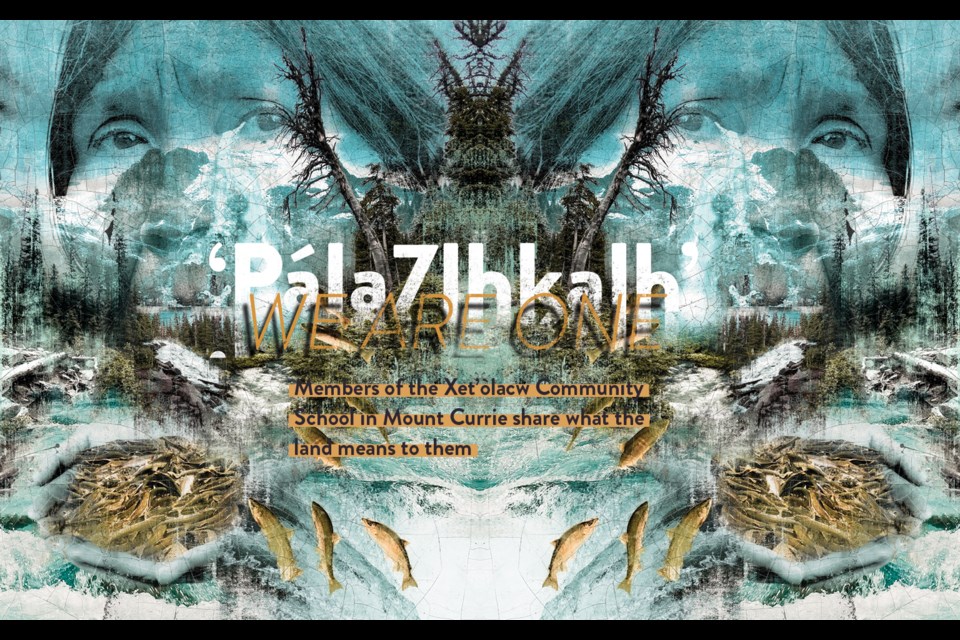

“A lot of the parents of these children are the products of the intergenerational effect of what happened,” says Andrew. “We are very fortunate to have had ancestors who kept asserting that we weren’t Canadian. Canada even went so far as to divide us. They were divided into these reservations. They didn’t even stop there. They divided our language. We are one—‘pála7lhkalh’—as St’át’y’emc Nation.”

Loud and clear

At the tail end of the worst wildfire season in B.C.’s history, the importance of taking a more traditional approach to stewardship and sustainability is not lost on Andrew.

A culture built on consumerism, capitalism and materialism is causing catastrophic damage to the lands we hold dear, she says.

“The message is coming out loud and clear. What is Mother Earth saying? It is burning,” she says. “Look at the depletion of our animals. Look at the depletion of the salmon in our rivers, the forest fires, the floods. Mother Earth is speaking out loud and clear.”

That message urgently needs to be heeded, Andrew adds.

“They continue to take and take. It’s very individualistic,” she says. “In our community, it’s communal. We need to survive as a nation, not just as a community.”

Although she didn’t fit the mould of contemporary Canadian academia, the education Andrew received in Mount Currie was more than enough to pass an entrance exam for Capilano University or its counterparts. This is when she truly saw the need for change—and the change she needed to make.

“I was very fortunate to have a grandmother and a mum who really fought to make sure I knew who I was. I knew my identity. I knew how to survive off the land,” she says. “I was very fortunate to learn from my Elders. I ended up graduating with a high self-esteem, high confidence, and wanted to continue my education. I couldn’t get into their schools because my way of learning wasn’t accepted yet. I didn’t have their English. I didn’t have their way of learning. That was all they accepted.”

Andrew was determined.

“I went back home and had my family. I came back to this school as a custodian. I worked my way up and got a Class 1 driver’s licence. I then decided that I didn’t want to stay a bus driver for the rest of my life,” she says. “I went back to school and got my teaching degree. I taught for nine years, but realized I couldn’t make the changes that needed to happen here. I went back for my master’s. Now, I am the school principal. It can be done.”

A living language

Andrew stresses this was only possible because she was able to learn her language and culture from Elders. When her grandfather’s children returned from residential school, he insisted English would not be spoken in their house. He wanted them to stay connected to their culture.

A psychology professor Andrew had in university helped change her own outlook on life, she says.

“I wrote an essay about my grandparents and alcoholism,” she recalls. “I said in the paper that my grandparents were passed out on the ground. I told them that I hated them and that I would never be like them. The professor pulled me aside and said it wasn’t my grandparents that I hated, but the system that caused them to be the way they were. They had their children taken away.”

That system impacted First Nations people for generations, in wide-reaching ways. Under the threat of being taken to residential school, Andrew’s husband was hidden in a cabin in Whistler when he was just five years old.

“My husband is a fluent speaker,” she says. “When the Indian agents came to our reserve to take the children, his uncle took the boys to Whistler. There’s a little lake where Nesters is now … There was a little cabin there. That’s where they were hiding.”

Today, students at Xet’òlacw now all have the opportunity to speak Ucwalmícwts—the Lil’wat’s traditional language—something many of their ancestors were denied. In Grade 8, Skil’ is writing her own book in Ucwalmícwts, and is rarely seen without her thesaurus.

“I love writing in my language,” she says. “I speak fluent Ucwalmícwts. I’ve been making my own book for three months now. I’m on the second chapter in my story. I hope to do more and hopefully I can be a writer when I grow up.”

Ucwalmícwts is directly tied to the land itself, Andrew explains.

“It’s a rich language,” she says. “We are so connected to the land. You can’t separate us from the land. Somehow, I feel like Canada knew that. That’s why they took us off our traditional territories and put us on reservations.”

It is important the kids feel no sense of shame in who they are and where they came from, Andrew says.

“One really important thing is for our children to know that it’s not their fault,” she says. “It’s not their fault. It’s not for them to be ashamed that they don’t know how to speak their language. That’s for Canada. Canada needs to be ashamed for what they have done to our people.”

The principal looks forward to what the future will hold, and the wonders her “survivors” will achieve in all aspects of life. These survivors will pass on their language, their culture and their identity to future generations.

“They are survivors,” says Andrew, of the students. “They are strong. Our ancestors are strong, they survived. Even the children that are in the ground are strong. They are still there, speaking loud and clear.”