When self-discipline fails and fear runs unchecked, the spiral into panic is not far off. Panic is uncontrolled, undirected fear and as such unproductive. It takes a huge amount of energy to panic, and you receive little enduring energy in return. Panic is great for lifting a car off a baby or fleeing a charging mastodon, but it is useless for getting out of a dangerous predicament in the mountains."

- Mark F. Twight, Mountaineer and author of Extreme Alpinism

Backcountry travel is intrinsic to Whistler's culture. The rewards of pushing beyond the boundaries are well known; fresh powder, relative solitude and a sense that one is living their life to the fullest. But no reward is gained without risk.

That risk is what we gleefully accept whether we are riding chairlifts in the resort or climbing to descend remote peaks. Some folk may go their whole lives without a story of Mother Nature reminding them of who is boss, but in Whistler there are many now-learned souls who have had to spend some unexpected nights in the mountains.

With that in mind Pique thought to share some of their stories, as well as some tried and tested advice about how to prepare before Mother Nature decides to keep you outside all night unexpectedly.

Some who spent the night out in the cold were prepared, some were not — but all share a common feeling at the end — relief at making it through and a commitment to not letting it happen again unexpectedly.

A day trip gone wrong

When Japanese ski instructor Kazuya "Kaz" Dobashi crossed the boundary for his first backcountry experience he believed he was well prepared. He was travelling with two other skiers and one snowboarder, their leader was a Japanese friend named Kawasaki, who had experience skiing the Blackcomb backcountry and who also worked for Whistler Blackcomb Ski School.

The group had their coffee over a meeting about the trip and checked their rental equipment at Glacier Creek before heading in to the alpine and towards the boundary. The goal for the day trip was to ski one lap of the popular line D.O.A., then return to the Blackcomb Glacier gate and hike towards Husume, which would feed them into Blackcomb Glacier for an easy ski out through the resort.

After the initial descent of D.O.A., the group ate a casual lunch at the Horstman Hut before heading out past the boundary once again. Elated about their first time having descended Blackcomb peak's steep, narrow and very rocky couloir, the group was looking forward to the longer, powder-filled descent on Husume, so much so that they decided to push through some incoming cloud.

It was at this point the party made a critical error — Kawasaki knew the way to Husume, and had skied it before, but he was now trying to navigate through a thick fog. Instead of dropping into the Spearhead Glacier to reach the ridge that would lead them to their goal, the party kept traversing along in the direction of Wedge Creek, constantly looking up and searching for the entrance to Husume. But they were one ridge east of where they thought and with the weather coming in they had lost their orientation.

"We finally found what we thought was the hiking point to Husume and began to climb towards it," recalls Dobashi.

"However we didn't take the time to realize that we were in the wrong place because it was much steeper than it should have been."

It was now about 3 p.m. darkness was setting in and the fog was showing no signs of letting up. Panic started to grip the group.

http://admin.piquenewsmagazine.com/whistler/a-night-out-in-the-cold/Content?oid=2453162"We rushed ourselves to get out of there and kept traversing as far as we could go, but nothing changed. We were all afraid of getting lost. I remember one member of a our party saying 'Hey! There are people over there! We should get some help from them!' But what we saw were just a few rocks far away that looked like humans. That was how mentally exhausted we were."

After several hours of traversing they finally reached the Spearhead Glacier, though no one was sure of their exact location. Kawasaki realized their error and knew all they had to do was cross one more ridge then they could ski straight into the Blackcomb Glacier and back to safety.

But they chose not to risk it. After the last several hours they were all physically and mentally exhausted and afraid of making another error in the near darkness. Their cell phones were either out of battery or not in service. It was time to think realistically about spending the night.

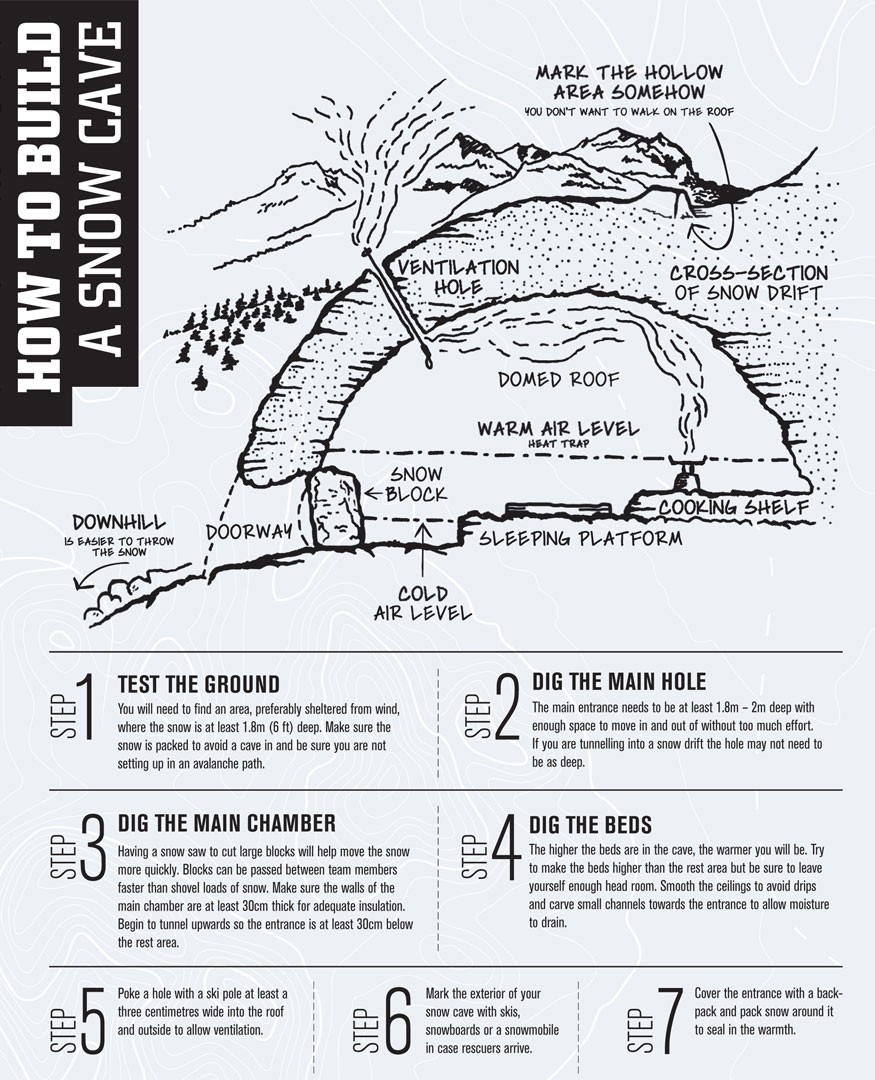

"We found a huge rock that was surrounded by a snow wall around it about two metres high with a gap in between," says Dobashi.

"We jumped in the gap and started digging the wall sideways. We really had to finish it before it got completely dark as we had no headlamps."

After team-shovelling their makeshift snow cave to the width of about a quad chair, everyone got inside and they sealed the entrance with a solid chunk of snow. The three skiers and one snowboarder huddled for warmth, with nothing but their clothing insulating them from the ice-cold floor of the cave.

"I was still freezing because my clothing wasn't very waterproof," says Dobashi.

"After the digging my pants and gloves were completely wet and frozen, making me even colder throughout the night. We were all freezing in the cave with no fire and no food but we tried to stay positive. We kept poking each other and taking turns talking with one another so that everyone stayed awake. I remember when I got out of the cave for a pee I saw a clear sky and all of a sudden lots of shooting stars, all streaking in the same direction. It may have been a hallucination."

When the group got up at first light they were greeted by a bluebird sky. Still freezing from their ordeal they didn't waste anytime soaking up the view — instead they got ready to ski out and were soon climbing up the final ridge. They could see Wedge Mountain to the north east, confirming that they were indeed on the correct ridge. At the top they could see their way into Husume and skied down to the Blackcomb Glacier — through the lightest powder snow they had ever experienced in Whistler. The thud of avalanche control by Blackcomb ski patrol was like music to their ears as they coasted along the cat track towards Whistler Village.

The unexpected overnight on the back of Blackcomb brought home for Dobashi that backcountry users, no matter how short they think their trip must always be prepared. After rest and recovery from his unplanned 2009 winter camping experience, he went out and bought himself a brand new ski jacket and pants — all Gore-Tex and fully waterproof — as well as a beacon, shovel and probe. In 2010 he did the excursion again — this time fully prepared.

A less-than-perfect storm

It was November 2007 when Luke Kolla and his friend Mike Nestee made a plan to journey out for two nights of camping and some alpine climbing near Birkenhead Lake, near Darcy, B.C. Both had just completed their adventure tourism diplomas through the Canadian Tourism College, Kolla had recently had an interview at a local snowmobile guiding company and both were keen to test their new skills and equipment on an early winter expedition.

"The weather was supposed to be great," laughs Kolla.

"We were checking the forecast for about a week and a half, we were looking at clear and cold conditions. It was early season conditions and the trip reports that we read said there wasn't much snow before the lake so we decided to go for snowshoes instead of skis for the hike in."

After driving about five kilometres up the logging road towards the gate for Birkenhead Lake Provincial Park, the pair came across a fallen tree blocking any further vehicle travel. Kolla parked his SUV and they continued on foot. After reaching the gate to the provincial park they turned onto the Phelix Creek trail, and though it was newly cut and had lots of visible markings there was still some bushwhacking involved. It ended up taking them about six hours to reach the shores of Long Lake from the car.

The nearby and comfortable Brian Waddington Hut was available, but the duo had already planned to spend two nights camping in their tent. They had all the equipment, and fresh out of outdoor school, wanted the real winter camping experience. After setting up camp the first afternoon they did a short hike of the area and planned their ascents for the next day.

"There's a nice saddle between (Mt.) Shadowfax and Aragorn, we were going to summit them both and if we had time, we were going to attempt Mt. Gandalf," says Kolla.

The next morning the climbers assembled the necessary equipment for the day; ropes, harnesses, crampons and ice axes. The sky had clouded over but there was still good visibility for their goals that day.

"By the time we got to the start of where we were going to rope up it had started snowing sideways," says Kolla. "We continued thinking it was just a brief flurry, but after the first pitch I looked down from about 10 - to 15-metres up the rock face and I couldn't see Mike, who was belaying me."

They both agreed to head back to camp somewhat alarmed that their snowshoe tracks had already been filled in by falling snow. Back at camp they made the most of their down time by practicing digging trenches and snow caves, determined not to use the four solid walls of the hut a stone's throw way.

"When the sun went down we started breaking out the rum and finishing most of the food we'd brought," says Kolla. "We were hiking back out the next morning so we wanted to lighten the packs a bit."

Slightly tipsy with full bellies, the two adventurers had not accomplished their goal this trip but were happy to have made a solid attempt. The snow had begun to taper off and they turned in around 11 p.m. with alarms set for 7 a.m. the next morning.

"We woke up and it was pitch black inside the tent," says Kolla adding that they were confused as to where all the sunlight was at 7 a.m.

"We looked up and we could see a small sliver of light coming in the top of the tent. The walls of the tent were solid and the vestibule was almost caved in. We had to dig ourselves out of our tent, and saw that only the top two inches of the tent were above the snow."

Luckily one of the vents on the tent was still exposed to outside air, had that been covered as well there would have been a real possibility of the climbers suffocating overnight in their sleep.

"That was the one thing that we screwed up on, we should have woken at some point in the night and checked that we weren't getting snowed in," says Kolla.

In less than eight hours, another storm front had rolled in dumping well over a metre of snow, much to the bewilderment of these two trained outdoorsmen. Nothing like this had appeared on any of the weather forecasts. It took over an hour to dig out the tent and after having a quick breakfast and loading up the packs, they set out for their return leg home.

"We would have been better off with snorkels and flippers," says Kolla, referring to the inadequacies of their snowshoes. Both men were hauling packs laden with over 30 kilograms of camping and climbing equipment, making every step laborious, the snowshoes doing little to stop their feet from sinking thigh-deep into the fresh snow.

"After plowing through it for about 45 minutes to an hour, we looked back and we'd come about 100 metres," says Kolla.

And it wasn't getting any easier. After reaching a clearing that they had passed through on their way in, with the metre of snow their exact route was now unrecognizable. One of the straps on Kolla's snowshoe had broken, rendering it useless. Taking an educated guess, they fortunately ended up on the right route, but soon had to cross several boulder fields, all coated in fresh snow. Both men repeatedly fell into the cavities between the boulders, snow above their heads and had to take off their packs and crawl out of the claustrophobic holes.

The flagged trail of Phelix Creek was not far away and after six to seven hours of wading through the snow, Kolla and Nestee thought the worst was behind them. But the snow had weighed down the low-lying branches, obscuring many of the pink-taped limbs. They only found about every fourth or fifth flag, each sighting giving them a temporary boost of confidence that they may actually make it to the car. But darkness set in, as did the frustration. Nestee desperately wanted to get back to his wife and kids, but trying to stay on course with nothing but the light of their headlamps proved futile. There was no other choice but to set up camp again. Up the tent went, and this time they woke up periodically to guard against another storm burial.

The next morning the duo awoke to find the pink tape just a few metres from their tent. The sun was out and their spirits rose with it. Navigating through the familiar looking logging slashes, it was about 2 p.m. when they first caught site of Kolla's Pathfinder. It gave them hope that they may just be able to get home that evening. But up close the dire situation of the Pathfinder became evident.

"We get down there and the snow was covering the wheel wells," says Kolla. "We break out the shovels, dig out the truck, dig out the road and try to turn the car around. But my bald-ass all-terrain tires were not going anywhere."

The sun was setting again, this would be their fourth consecutive night instead of the planned two. The climbers took comfort in the fact that they could start the car, dry their gear and sleep inside the vehicle that night, but food was running low with just a few handfuls of trail mix left and there was still no cell phone signal. At no point were they worried about not making it out, they had seen some houses on the road to Birkenhead Lake and the plan was to hike back, knock on doors and use a phone to alert family and friends that they were OK.

"We weren't injured, we weren't lost. Our biggest worry was everyone else was worrying about us," says Kolla.

And that was exaclty what was happening. Nestee's wife Deeanne had called the RCMP the morning after their expected return, which prompted Pemberton Search And Rescue to initiate a search. The next morning Kolla and Nestee set out at 8 a.m. and had only hiked a couple of kilometres before they heard the thwap of a rescue helicopter.

On the heli ride back to Pemberton, one of rescuers was grinning at Kolla, but after the ordeal of the last 48 hours, Kolla couldn't quite place the face.

"I'm Craig Beattie, general manager of Canadian Snowmobile," said the rescuer with an outstretched hand.

"I interviewed you for a job with us last week."

Kolla sheepishly shook his hand, embarrassed that his prospective employer had just had to come rescue him from the backcountry. He got the job.

Snow caves, hors d'ouvres and Canadian men in Canada

It was February 2004 when Paul Wilson got the call to go snowmobiling in the alpine of Sproatt Mountain. Back then the steep, side-hill access through the tree line known as "The Staircase" had no built road or groomed trail, snowmobilers had to spend hours punching through deep snow in tight trees.

Wilson, his friend Paul Martin and another friend (who will remain nameless but known to friends as T-butt) were meeting another group of snowmobilers to get shown around the playgrounds of Sproatt's alpine terrain.

"We were supposed to meet another two friends (at the parking lot) to show us the way," says Wilson.

"We were running a little bit late so they took off about 10 minutes ahead of us and we were going to catch them up at Fuel Drop."

But when they arrived at the group of peaks known as Fuel Drop (sledders drop their spare fuel here to retrieve later) there was no one to be seen. Phone calls went unanswered and there were no engines audible in the vicinity. There were some tracks leading downhill towards the alpine meadows below, which Wilson and his friends decided to follow in the hope of catching the other group before calling it a day. The untracked terrain around them beckoned — a lethal siren call.

"After a while we couldn't look for them anymore, we had to do some snowmobiling," says Wilson, now knowing full well where the trip went wrong.

"We kind of had an idea of where we were going, but not exactly. None of us had ever been there before. We'd looked at it on a map, but that was it."

Distracted by carving their sleds through head-high powder, the group did not notice the weather changing quickly, a dense fog with heavy snowfall enveloped them in less than 20 minutes. They made the decision to retrace their entrance tracks into this bowl and head back down the Staircase.

All of a sudden the riders could not see the snow in front of their own front bumpers. Their tracks were filling in fast and were barely visible in the fog. The crew was inadvertently driving their sleds straight into sink holes and snow banks, requiring laborious digging to get out. T-butt managed to crash his sled into a creek, his unreliable engine refusing to start.

Now down to two sleds and three riders, all soaking wet from perspiration and precipitation, they could not tell whether the barely visible tracks they were following were leading them towards or away from their goal.

"After digging for about an hour it was three o'clock and it was starting to get dark making it even harder to find our tracks," says Wilson.

"We got really confused and turned around because we couldn't see 10 feet in front of us."

Wilson made a few phone calls but no one was up on the mountain anymore, all the other sledders had retreated back to the parking lot hours earlier. The group made the decision to find a place to hunker down for the night and found a suitably sheltered cluster of trees to set up camp. A tall snow bank was excavated as a make-shift snow cave, and luckily, having a small saw handy they could cut limbs from trees as firewood. With two snowmobiles they had plenty of gasoline to help keep the fire going.

Everyone emptied their backpacks to see what combined resources they had to get through the night, Wilson and Martin had diligently brought spare underlayers, toques and plenty of food in addition to their avalanche safety equipment. T-butt was not as prepared.

"We opened up his bag and he had half a sandwich and a bottle of Gatorade, that was it," says Wilson, shaking his head in disbelief as he recalled the story.

But with a bunch of granola bars, sardines, smoked oysters and crackers (Martin was working as a chef at the time) there was enough food to get them all through the night. However, T-butt, soaking wet with no spare clothes, was having trouble warming up even with a fire going.

"I gave him my upper-body layer, (Martin) gave him his lower-body layer and we even taped our spare toques to his feet to use as socks," says Wilson.

Wilson had meanwhile phoned his friend Dave Bryce, an experienced snowmobiler who knew Sproatt Mountain extremely well. Bryce had offered to gather help and come up to look for them in the dark, knowing full well how difficult a night search would be.

But as the hours dragged by and it began to sink in that they might be spending the night outdoor fear began to take hold of T-butt — as the least prepared for such a scenario he was the first to show signs of despair.

"He got scared and started feeling like we were going to die," says Wilson, recalling the panic he saw in T-butt's.

"I started to feel it too after a while, all of sudden I was questioning myself on whether we were going to make it. We were so tired and it was snowing harder and harder. Then (Martin) came up with the line, 'We're Canadian men in Canada.'"

It was the mantra that kept their spirits treading water, helping then resist the spiral into desperation.

On the phone again to hear the reassuring voice of Bryce, the group reluctantly gave the go ahead to call search and rescue (SAR). Wilson and Martin were confident that they could make it out the next day, but T-butt needed the reassurance that professional rescuers were coming to help them. That call meant they had to then stay put until they were found, however long that was going to take. SAR was unable to initiate a search until daylight, so Bryce and some other devoted friends continued the night search. While Martin and T-butt tried their best to sleep propped up in the snow cave sitting on their helmets, Wilson — who couldn't stand it inside the cramped shelter — busied himself by cleaning the snow off the two remaining sleds and occasionally ripping a lap to show headlights and make some noise in case the rescue party was close. Phone batteries were nearing depletion and there was still no sign of a rescue coming that night.

Despite the temperature being only around -5C, the moisture made it feel much colder. Fighting off frostbite and the onset of hypothermia, the men kept mumbling to themselves "We're Canadian men in Canada."

The next day the group's spirits lifted somewhat with the brief break of sunshine. SAR crews were standing by at heliport ready for the weather window to fly and locate the missing snowmobilers. Preparing for the possibility of staying a second night, the group had a productive morning, properly lining the snow cave with tree limbs and gathering enough firewood to burn for the entire next night. With careful rationing they still had some food left but bottled water was running low.

At noon they heard the flyby of the SAR helicopter, but there was no attempt to land. Still, it was reassuring to hear machinery other than their own sleds. Help would not be far away now.

At about 3 p.m., when the light was beginning to fade again, the three exhausted men heard the high pitched whine of 2-stroke engines. Walking up from their camp they saw two friends, Doug Washer and Jeff Kyle, carving expert turns down the hill toward them, motorized guardian angels enjoying the heavenly descent towards their camp.

The abandoned sled was recovered and the group returned to Sproatt Lake through treacherously deep snow. Wilson's coworkers and friends Matt King and Jeff van Driel awaited them at the lake, all ready to assist in the search. All rejoiced in the fact that everyone was OK and Wilson, Martin and T-butt, the Canadian men who had survived a wintery night in their own countryside, bought dinner, beers and a few special bottles for their rescuers in appreciation. Wilson and Martinstill go snowmobiling together and Martin still drives the same sled 10 years later. T-butt has never gone snowmobiling again.

The rescuers

"More than 85 per cent of the calls from overdue backcountry skiers that we (respond to) involve people that have overnighted," said Whistler SAR team manager Brad Sills, a 35-year veteran of the organization. Calls from lost parties requiring rescue usually come late in the afternoon or evening when people have exhausted all other options, but SAR is unlikely to initiate a rescue if there is little daylight left.

"We're not trying to punish people, but you cannot find people at night time," says Sills. "You can't travel outside the ski areas after dark without certain risks to the rescuers."

When SAR receives a rescue call from the RCMP it will designate an urgency rating based on the victim's age, medical conditions, the number of subjects in the party, cumulative experience in the party, the equipment carried and the weather at the time of the call.

"If you're a 13-year-old girl by yourself with diabetes, we're going to go out because you're probably not going to make it through the night," says Sills. "If you're a 30-year-old male with two buddies with no medical conditions, and the weather is -4C, chances are you're going to be spending the night out."

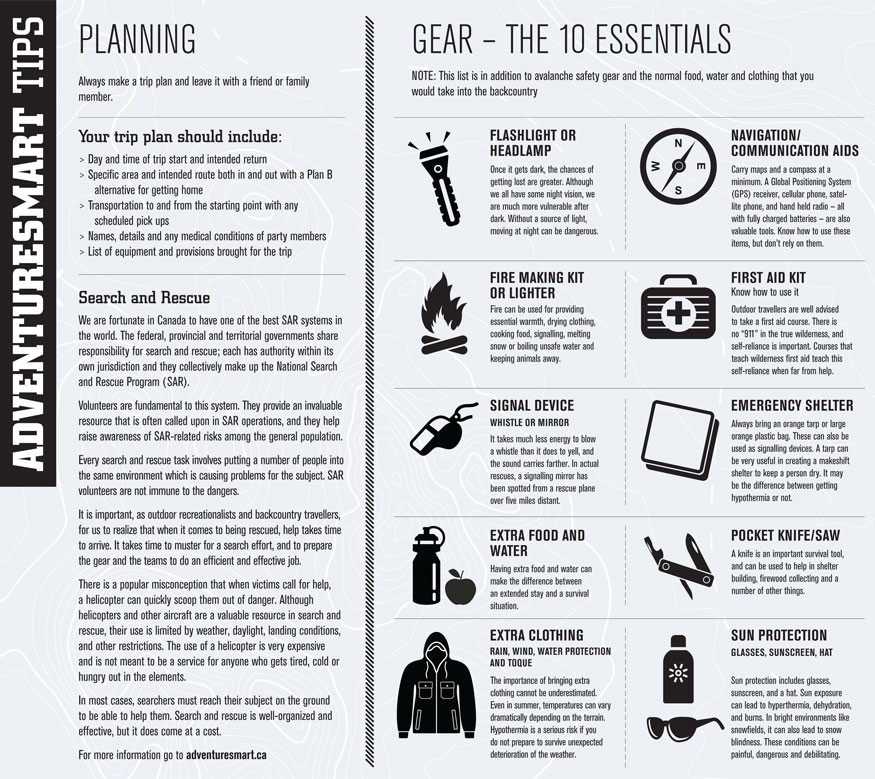

Sills reinforces that a night out in the backcountry is not as difficult or scary as it sounds providing travellers are adequately prepared. That means carrying more than the minimal survival gear of a transceiver, shovel and probe (see sidebar for complete equipment list.)

"Of that 85 per cent (of unprepared travellers) that we are called to assist, most have virtually no gear at all. They have the clothes on their back, a candy bar and if they are smokers they may have a lighter. Those are the people that are the most at risk of having a really poor night."

The climate in Whistler typically does not dip into the ranges of severe cold with the odd exception of a cold snap once or twice a season. The range of -4 to -10 degrees C is usually what those caught overnight outside have to endure, though the likely scenario of getting wet can increase the severity of the situation. Not having spare, fresh layers or the ability to start a fire can mean a much more uncomfortable night in the backcountry. Water courses, such as creeks and riverbeds, should always be avoided if possible — the cool air and moisture surrounding them can make a sleepless night even more miserable.

But the most dangerous enemy of a night out in the winter wilderness is emotion.

"It's the fear that causes the problem," said Sills.

"With minimal equipment you're going to be able to spend the night and be able to chuckle about it the next day. But if you've gone out and not prepared and fear sets in, chances are you're going to be crying when we find you the next day. Doing an overnight shouldn't be something that terrifies you, if you're going out of bounds you should be prepared to spend the night and you should probably have done it once or twice, even if it's in your own backyard."

But Whistler's visitors account for more rescues than wilderness-savvy Canadians and cultural idiosyncrasies can play a part in getting foreigners into trouble beyond the boundaries of Whistler Blackcomb. For example, in the European Alps, descending into an adjacent valley will simply mean buying a lift ticket for another ski area to return via their lift system, or paying for an expensive cab ride back to your hotel in the neighbouring town. Visitors to Whistler see tracks descending past boundary signs and sometimes assume it leads to a developed area.

"Certainly a good deal of the call volume that we do is near boundary," said Sills.

"The backside of Whistler is a favourite place and Wedge Creek is starting to become more popular for the uninitiated. There's much nicer places to spend nights in Whistler than in creek beds."

Sometimes people take notice of the boundary signs, occasionally they choose to ignore them.

"Even though the sign line is demarcated extremely well, it is possible in the certain weather conditions to breeze between posts. Then you get the people who say they didn't see any signs at all, but when you look through their camera you seem them posing in front of (the signs) laughing."

For Sills the lesson is clear whether you are journeying past a resort boundary or setting off into the remote wilds of Canada's grand landscapes: Be ready for every expedition to potentially turn into an overnight trip and carry the equipment and provisions to do so.

Search and Rescue should always be the absolute last resort to get you home.