TheTyee.ca

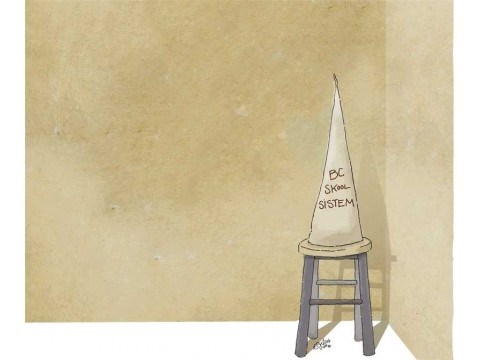

The current quarrel over school funding sounds familiar to old-timers. Just as in the 1980s, school boards are laying off teachers and closing schools, while the education minister says they've never had it so good. Who's telling the truth? And does it even matter?

The Liberals have consistently argued that education gets more money every year, and that the teachers and trustees are misrepresenting the situation in their endless demands for ever more funding. Their "shortfalls," we're told, reflect only their endless wish list of inessentials.

One way to judge the merits of the dispute is simply to look at the average operating grant per student in constant dollars. (The amount varies from district to district, but we're talking about the provincial average.)

Is inflation confusing the true level of funding?

That's too simple, says John Malcolmson. He's the CUPE research representative for the kindergarten to Grade 12 (K-12) sector, and has decades of experience in studying school funding. A yardstick based on the consumer price index, he observes, doesn't work for education: "School districts don't buy groceries." What's more, schools are spending money differently from 10 years ago as needs have changed for various education services.

Dealing with 'structural funding shortfalls'

In a March 15 briefing note to CUPE and other staff-support unions in K-12, Malcolmson defined "structural funding shortfalls" in the schools: They occur, he said, "where available district revenue falls chronically and persistently below that required to fund and maintain publicly mandated programs."

He drew that definition from Joan Axford, secretary-treasurer of School District 63 (Saanich). To explain school funding problems in general, and Saanich schools' problems in particular, Axford has created two memorable PowerPoint shows. (Look for them in the right-hand column of the Saanich district home page .)

One, on "Learning from the Past," is a brilliant and concise history of school funding since the 1980s. The other, "Public Budget Meeting Presentation," was made to the board on April 21. It shows the provincial picture and then uses Saanich as an example of structural shortfall.

Axford shows that education in 1991 took 26 per cent of the provincial budget; in 2000-01 it fell to 20 per cent, and this year it's just 15 per cent. Per-student funding seems to have gone up from $7,097 in 2005-06 to $8,381 in 2010-11.

But with cost pressures factored in, the operating grant per student has actually fallen from $6,409 in 2005 to $6,289 in 2010-11.

Saanich has seen a steady decline in student enrolments: the district lost just over 1,000 students between 2002-03 and 2006-07, and expects to lose almost 1,200 more between 2007-08 and 2013-14. Axford estimates that a fall of 200 students reduces costs by $690,000. But the funding allocation is reduced by $1,348,000 -- leaving the district with a net shortfall of $707,000.

One impact: since 2004-05, Saanich has lost 38 full-time equivalent teachers due to enrolment decline, but almost 16 FTE teachers to cover the cost of structural deficit reductions.

Selling the family jewels

Having built up financial reserves over years, Saanich has been using those reserves to balance its budget since 2003. It's an ongoing process: school closures in 2005-06 and 2006-07 generated almost a million dollars in savings. All told, the district has just over a million dollars in reserves this year. But it's been selling the family jewels just to pay the bills.

Saanich still faces continuing cost pressures for 2010-11 that total $1.36 million, including HST ($102,000), carbon offset tax ($83,000) and B.C. Hydro rate increases ($26,000). Other costs beyond board control: MSP premiums ($55,000), teacher salary increases ($609,000) and teacher pension rates ($311,000).

These cost pressures since 2006-07 have produced a wide gap between cost increase per pupil and government funding to cover that increase. This year, the cost increase was $2,024 per pupil, and Victoria raised funding by just $454. Next year will see another increase, of $2,245, with only $458 more in government funding.

Between revenue decline, cost pressures, enrolment decline and loss of reserves, Axford estimates that Saanich's total structural funding shortfall in 2010-11 will be $3,342,515. Since 2000-01, Axford says, the 10-year shortfall for Saanich has totaled $13.67 million.

Meeting next year's shortfall could involve cuts to student services such as learning assistance, education assistant time and speech and language therapy. It could also mean cuts to libraries, reading programs and non-enrolling teachers in middle and secondary schools - presumably including most teacher-librarians.

Saanich is worth considering not because it's an extreme case, but because it's fairly typical. CUPE's John Malcolmson says 52 of our 60 school districts are dealing with falling enrolments this year.

(In the case of the Sea to Sky School District, the board last week admitted that it was facing a shortfall for the 2009-2010 school year if regular funding increases were approved, and will cut its budget this year. However, there are no teacher layoffs planned, and any cuts to meet the budget will likely come from library expenses and reviewing staff hours.)

Much room for improvement

The public system also suffers from another financial drain. Some $200 million dollars in tax money is funneled into subsidizing private education instead of public schools. Whether that's an efficient allocation of education dollars is up for fierce debate (see sidebar).

When polled last year, 65 per cent of British Columbians said public funding of private schools should end. And more than 81 per cent said the provincial government is not doing enough to fund public education.

For all the government's bragging about the excellence of our schools and their high funding, its own documents reveal some abysmal failures.

According to page 19 of the B.C. budget for education , from 2008/09 to 2010/11, adult British Columbians (aged 16 to 65) who could read at "level 3" in 2005 was just 60 per cent. With luck, that number may have risen to 69 per cent this year. (Level 3 is defined as "the desired threshold for coping with the increasing skill demands of a knowledge economy and society.")

In other words, a minimum of 31 per cent of adult British Columbians can't read well enough to understand this article. That's about 880,000 of us. It does not speak well for a government that made literacy the first of its Five Great Goals .

On page 13 of the same document, the ministry says that in 2006-07, 80 per cent of high school students had graduated within six years of entering Grade 8. Its target for this year is 83 per cent.

In other words, we are sending at least 17 per cent of our young people into a tough job market without high school completion.

For Aboriginal students, the graduation rate in 2006-07 was 48 per cent. The Liberals hope to see that rise to 60 per cent this year. So we are willing to let two out of every five Aboriginal kids go into the world without even the paper shield of a Dogwood Certificate. (In 2007-08, we had just over 60,000 Aboriginal students . So 24,000 of them will have to survive without high school graduation.)

After a decade of structural shortfalls, perhaps it's no wonder we're doing badly. But we weren't doing much better even in the relatively good years of the 1990s. Most of the students in that decade had, after all, been hurt by the cuts of the Socred restraint era, when Bill Bennett downloaded unwelcome costs onto the kids then in school.

Until we decide as a province that education is a true and continuing priority, the schools will go on suffering a financial brownout: enough money to function, at the cost of the poorest families. And that in turn will cause an intellectual and economic brownout for all of us that will continue indefinitely into the 21st century.

SHOULD YOUR TAXES HELP FUND PRIVATE SCHOOLS?

Back in the 1960s, W.A.C. Bennett absolutely refused to put tax money into private schools. It was a matter of principle: If you didn't like the public schools, you could pay the whole shot to put your kids in something better.

In 1977, his son Bill reversed that policy and began subsidizing families who thought the public schools weren't good enough (or religious enough) to suit their kids. It bought a lot of votes, and it still does. That subsidy by 2008-2009 was supporting over 54,000 students in Group 1 private schools at 50 per cent of their local public-school district's per-pupil spending. Another 14,000 were in Group 2 schools receiving 35 per cent of that spending. (They call themselves "independent schools," but they're clearly dependent on their subsidies.)

All told, B.C. taxpayers spent just over $200 million in 2008-2009 to support 319 private schools, plus another $41 million to private "distributed learning" schools and $25.4 million in special education grants to qualifying students in Group 1 and Group 2 schools. The BCTF says funding to private schools has risen by 34 per cent while public-school funding has risen by just 13 per cent.

The Ministry of Education defends this by saying, "To educate the 69,913 independent school students in the public system would cost $531 million in operating grants to public school districts (based on the average 2008/09 school district per student operating grant of $7,595). This is $275 million more than the total current operating grants allocated to independent schools."

In principle, those students have every right to an education in the public system, and we would have to find the money for them if they enrolled. In practice, thousands would stay in the private schools and their parents would just be out of pocket a few thousand extra dollars every year. In the meantime, putting a quarter-billion dollars and a few thousand more kids back into the public system would solve a lot of problems. - C.K.