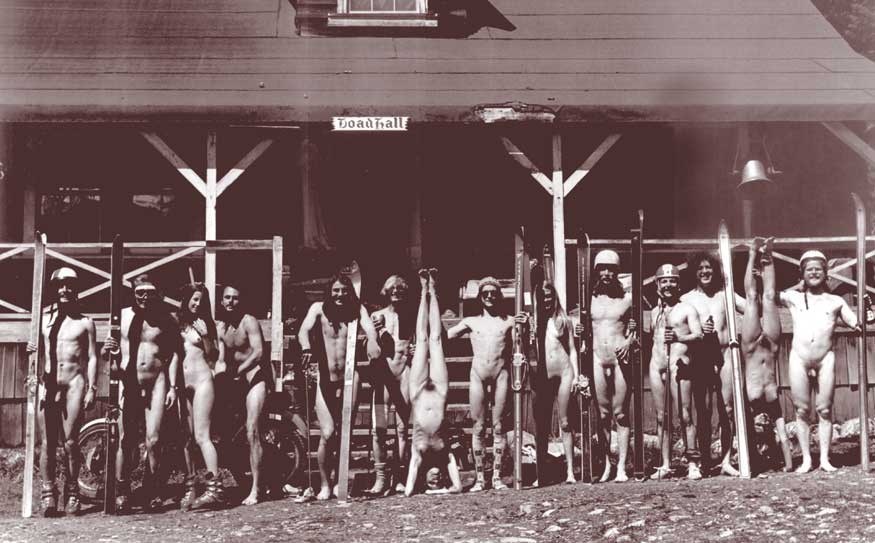

At the Whistler Museum's recent Icon Gone event the Toad Hall skiers were brought up, once again, as Whistler icons — "sacred images or figures." And perhaps they are, for they represent what Whistler was premised upon: baby boomers of northern European background. The Toad Hall gang also happened to be free-spirited and crazy about skiing.

Just about everything Whistler has done or built since the first lifts were dropped on Whistler Mountain has been based on the assumption these icons would continue to exist. But hard facts are finally challenging that assumption.

If skiers and boarders are the fuel that powers Whistler we are, like the auto industry, heavily reliant on a dwindling and finite fuel source. As the Canadian Ski Council has observed, "We have a gradually declining number of active participants skiing and riding fewer days per season." The trend is similar in the United States.

Skiers and boarders are, of course, not the only people fuelling the Whistler economy, they are just the first group that comes to mind.

In the 1980s and `90s, when Whistler was being built, the real estate market was driving the local economy. True, most buyers were skiers and, later, snowboarders but it was their buying of condos and cabins that fuelled the town.

There's little development in Whistler these days and, across Canada, there's not much appetite right now for buying real estate. A survey by Ipsos Reid for RBC released this week found that, despite low mortgage rates, home buying intent is down across the country. That's not quite the same thing as a survey of people's intent to buy a second home in Whistler, but Ipsos Reid found Canadians generally are still wary about the economy and at the moment reluctant to put their savings into real estate.

Some of that behaviour has to do with consumers' expectations. In the last five years they have been shaped by the global recession and the rise of comparison shopping on the Internet. We all expect a bargain now. Whether we're shopping for real estate, a vacation or underwear, there's an app or a website that will compare prices, availability, colours, performance, reliability or any other criteria that are important to us.

Another factor that challenges Whistler is the changing face of Canadians. By 2031 one in three Canadians will belong to a visible minority, according to Statistics Canada. For various reasons, including the fact that it needs people to fill jobs, Canada maintains one of the highest rates of immigration in the developed world. The vast majority of immigrants to Canada come from Asian countries, nations where skiing and snowboarding are not part of the culture.

The face of destination tourism is also changing. A study by the Tourism Industry Association of Canada and Deloitte found: "With our larger source markets (U.S., U.K.) shrinking, we are relying more and more on emerging markets to drive our arrivals growth, and we expect this trend to continue for some time."

But perhaps the biggest threat to a place like Whistler is the relative "poverty" of the next generation, the millennials. This week the Globe and Mail and the New York Times both looked at young adults and both concluded that they have less money than their predecessors, the boomers.

"An overlooked story in today's economy is the stunted income growth experienced by much of the population," the Globe's Rob Carrick wrote. "But no group has been affected like young adults. People aged 20 to 24 years are 41-per-cent worse off financially than their counterparts were in 1976, Statistics Canada data show."

And it's not just Canadians under 30. "The trend in total median income (employment plus investment income) among people up to their mid-40s is for them to be poorer than was the case decades ago."

The New York Times came to similar conclusions about American millennials.

"And new research from the Urban Institute augurs that this emerging income gap is compounding into a wealth gap. The institute's research shows that even as the country has grown richer, Generations X and Y. (meaning people up to about age 40) have amassed less wealth than their parents had when they were young. The average net worth of someone 29 to 37 has fallen 21 percent since 1983; the average net worth of someone 56 to 64 has more than doubled."

While both papers note that millennials are likely the best-educated generation ever, that won't necessarily make them big spenders at any point in their careers.

"There is a persistent fear that they have entered a permanently lower earnings and savings trajectory. Even if the generation recovers, even if it ends up wealthier than the one before it, the scars will be deep and long-lasting," the Times concluded.

The point here is not that Gen X and Y or immigrants of Asian background are never going to want to ski or snowboard or vacation in the mountains. It's that sliding on snow is less likely to be a significant part of their lifestyles than it has been for boomers, the icons Whistler was built for.

And so the question is: can Whistler adapt and become relevant to the new generations that follow the boomers?