Water security and climate security are inseparable; one is implicit in the other.

Such is a main conclusion of a new report published by the United Nations University's Institute for Water, Environment and Health (UNU-IWEH).

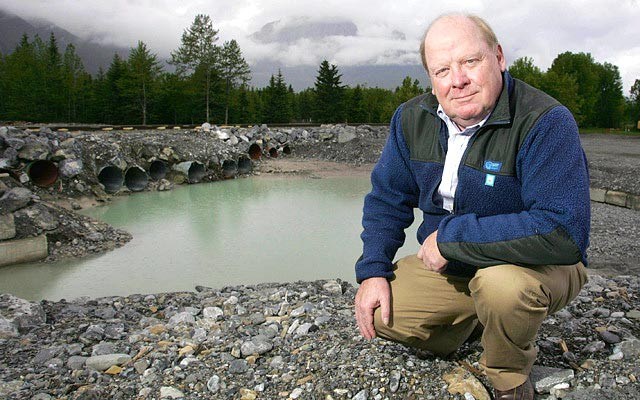

And, said Canmore-based water expert Bob Sandford, the UNU-IWEH's newly appointed Epcor chair for water security, and the report's co-author, all current water management challenges will be compounded one way or another by climate change and by increasingly unpredictable weather.

"The intensification of the Earth's hydrological cycle has been brought about by changes in the composition of our planet's atmosphere for which we are responsible," Sandford said. "These changes demand that water security now means managing not just the water you once thought was reliably available to you; but also managing water in greater extremes of abundance and scarcity."

March 2015 was the 357th consecutive month in which temperatures were above the 20th-century average, globally.

In response to that reality, Sandford's role is to understand water security threats from a global perspective, and then bring positive examples to bear at individual nation state levels — and, in particular, to bring the benefit of that knowledge back to Canada.

"There are a lot of places that will be addressing water concerns, whether it's too little or too much," Sandford said. "The hydrologic cycle has changed so much that climate circumstances are increasingly variable and uncertain. The hydrology of all of Canada is accelerating. Permafrost is melting in the Arctic and northern forests and tundra are experiencing fires of magnitudes never experienced before. Glaciers are disappearing and precipitation patterns are changing in our western mountains. While land-use changes and increased flooding are, for the moment at least, part of a new hydro-climatic circumstance on the prairies, deep and persistent drought remains a serious threat. In part because of prairie flooding, algal blooms of 17,000 square kilometres in area have begun to appear in Lake Winnipeg. Meanwhile, sea level rise and higher storm surges are plaguing all three of Canada's coasts. Hydrologically, Canada is becoming a different place."

To those who suggest the Earth's hydrologic cycle has always changed and fluctuated, Sandford replied yes, it has, but then added never at the current rate, and with virtually nowhere left on the planet that has not been altered by humans.

"There has never been 9 billion people in the world – we're currently at 7 billion, but we're projected to hit 9 billion," he said. "And we've never seen the rate of hydrologic change so rapid. Our policies are moving along at five kilometres an hour, while the problem of hydroclimatic change is moving along at 15 kilometres per hour, and accelerating. It is getting away on us. That's the problem."

Not so far to the south, for the first time in history, last week California's governor implemented state-wide mandatory water restrictions to reduce water usage by 25 per cent in response to a severe drought that has persisted for four years.

Canadians, Sandford said, would be wise not to dismiss California's woes as something happening "down there." Currently, Canada's Prairies are experiencing a cycle of big storms with potential flooding.

"But we have to think ahead and ask, through what invisible hydrologic thresholds might we pass as temperatures continue to rise, that may lead the hydrologic coin to fall on its dry side?" Sandford said. "That has to be in the back of our minds, always. We're not as well prepared as we need to be. There's a great deal of slack and wastage. We avoid crisis by preparing for changing circumstances."

Sandford, whose acceptance of the four-year post, hosted by Ontario's McMaster University, was announced in tandem with the report's release, explained that since Earth's climate is no longer stable, what humans and societies have grown accustomed to believing is sustainable, no longer is. Meanwhile, the infrastructure that supports much of modern society was built to withstand and react to those climate patterns that no longer exist.

"Historical predictability, known as relative hydrological stationarity, provides the certainty needed to build houses to withstand winds of a certain speed, snow of a certain weight, and rainfalls of certain intensity and duration, when to plant crops, and to what size to build storm sewers," Sandford said.

"The consequence is that the management of water in all its forms in the future will involve a great deal more uncertainty than it has in the past."

As a result of the loss of relative hydrologic stability, political stability and even economic stability in some regions are now at risk.

"On a global scale, failure to adapt to climate change leads first to greater vulnerability to extreme weather events; food crises; water crises; large-scale involuntary migration; and further man-made environmental catastrophes, which in turn lead to biodiversity loss and Earth system collapse," Sandford said. "The failure to adapt to climate change has even more devastating effects at the national level where it can generate fiscal crises; unemployment; profound social instability; the failure of national governance; internal interstate conflict; terrorist and cyber-attacks resulting in ongoing state crises leading to potential collapse. These risks are not theoretical. They are real."