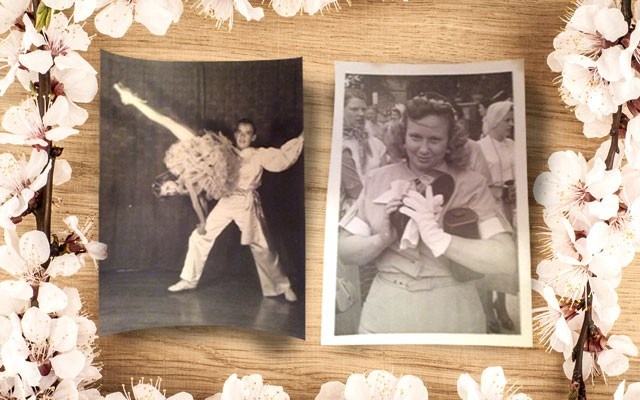

She was, in the vernacular of the time, a looker. Soft brown hair, loving eyes, legs that didn't stop. He was, well, let's be generous and say there were three things she found attractive. He was, in her words, a very clean boy, something she found important and lacking in her other suitors. He could dance, oh yeah, he could dance. And he was hopelessly in love with her.

He was an only child. She fell somewhere in the middle of a family so large I often thought I'd never run out of aunts, uncles and cousins.

It wasn't a whirlwind romance but it was a whirlwind wedding, a wham-bam, I do, ma'am affair near where his ship was momentarily in port. A weekend leave wedding and honeymoon all rolled into one before he sailed back into the war.

When that ended, he came home and they joined the rest of what would come to be called the Greatest Generation, doing their part to create the Baby Boom.

When my mother gave birth to me, lo those many years ago, she, with some small contribution from my father, created the perfect family. A boy for you, a girl for me, tea for two and two for tea. My older sister had blazed the trail a few years earlier, relieving me from any chance of being an only child.

Perfection lasted only three years, at which point a brother came along, followed in another three years by a sister. After which, thankfully, I believe they started drinking tea.

My mother was a strong woman. Any woman raising four children in the 1950s was. To her fell the long list of domestic duties so neatly defined by gender. My father went to work each morning; my mother worked all day at home, rustling kids, keeping house, preparing food, nursemaiding countless traumas, tending to the endless tasks that put the bliss in domestic bliss. My father came home at night, unwound, relaxed; my mother worked all evening, long after we were put to bed. My father did dad things on weekends; my mother... well, had it not been for the weekly, Sisyphean challenge of hustling us off to church, I'm not certain she would have known what a weekend was. Her work never ended.

Lest this sound like a life of domestic drudgery, let me assure you, it got worse. Not infrequently, my father worked out of town. When that happened, she picked up the slack and performed whatever tasks he took charge of around the house... reading the paper and enjoying a beer after work excepted.

And when my brother, at a tender age, earned the only two 'A's he ever received — Asthma and Allergies — something for which we still thank him since it necessitated a move to sunny Arizona from the cornbelt of Iowa, she became a single mom for what seemed like months while my father established a home and job in Tucson.

Thus began her first great travel adventure. In 1959, she loaded three children, one surly teenager, enough clean clothes for five days of travel, picnic hampers, a cooler of drinks and as many boxes she could stuff into the back of our un-air-conditioned station wagon and pointed it west. To further crowd both space and psyche, she also loaded up her mother-in-law.

Although orientation and map-reading were never her strong suits, the farmlands of Iowa slowly gave way to the Kansas prairie, the Oklahoma hills, the Texas panhandle, the high desert of New Mexico and, finally, the magic of Arizona. Being eight years old and raised on a steady diet of TV westerns, I was enthralled. This was cowboy country.

My mother — with the often-absent support of my father — somehow managed to successfully raise the four of us. Wasn't always easy and wasn't always pretty but none of us ended up in jail... or living in her basement.

And when the last of us trundled off to college, she and my father left the country. By the time we discovered they'd left, they were settled into the first of what would be a string of homes in world capitals, from which they set off on endless globetrotting assignments that would take them on the adventure of their lives, strengthen their commitment to each other and forging a bond that lasted until each took their last breath.

My father took his last breath a little over four years ago. It followed his last heartbeat. I heard them both. Then silence.

The thought struck me, as it had a few months earlier when I'd listened to the same silence fill the chest of my Perfect Partner, how strangely accurate, if tautological, the phrase, "He/she died so suddenly." really is. Even though both deaths were an inevitability months before they happened, one moment there was the slowing rhythmic thumpa-thumpa of their hearts, a sound we all hear first, albeit unknowingly, while swimming in the amniotic comfort of the womb. Then... nothing. A growing anticipation of another thumpa that never comes. A silent rush to eternity.

I listened to the same silence form a month ago, my ear to my mother's chest. With no dramatic final exhalation of breath, she slipped gently into that good night, happy to rejoin her lost soul mate.

Her final days were, somewhat unsettlingly, filled with an almost giddy anticipation of her own death. She'd dreaded much of her life since my father died, dreaded awaking in an empty bed and crawling back into it at the end of her day. She was ready, her bags for the afterlife were packed and waiting by the door.

It fell to me to tell her what we all thought was just another illness of age was actually her ticket to board that train a'comin'. She smiled at the news, perhaps feeling fully satisfied at her own prescience, having proclaimed two years ago she'd make it to 90 but no further. We'd gathered to celebrate her 90th birthday one month earlier.

Life goes on. Mine, not hers. Not theirs. Photographs, memories, an empty apartment, two urns in a granite vault, baking in the Arizona sunshine. A few loose ends to tie up.

There's no way to end a story about an ending.