Humans and black bears have been neighbours since the first fishing lodge opened in Whistler, so what does it mean to live in a community where the two dwell so closely side-by-side?

Everyone has great bear stories first off.

I remember my first sighting. Just returning from a Halloween party dressed up like a fortuneteller, I was walking home and heard a grunt. Not more than a stone’s throw away, a large bear ate from a garbage bag outside of a Nordic home. He/she looked at me and I turned and ran to the neighbouring house. My first thought should have been to call the conservation office bear line, but instead I fretted over the possibility of the following day’s newspaper headline reading "Fortune teller couldn’t predict bear attack". A new Whistler resident three years ago, I just didn’t know any better.

If I had known better, I would have phoned the conservation office hotline to report the homeowner who would have been fined for mismanaging attractants.

If I had grown up in the Whistler education system where bear education is part of the school curriculum, I would have backed away slowly from the bear making as much noise as I could.

If I had educated myself on what it means to live in black bear habitat, I would have known bear attacks in the area are rare to non-existent. (Over the past 13 years of studying bears in Whistler, Michael Allen knows of only one bear attack incident that occurred in Pemberton.)

If I had lived a little longer in Whistler, I would also have known the problem was not with the bears, but with the relationship between humans and bears — a relationship that leads to the destruction of bears with very few repercussions for humans.

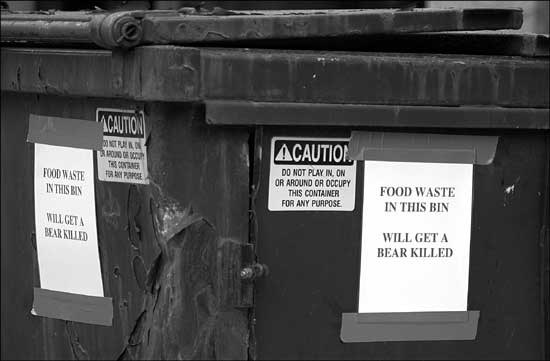

If everyone knew leaving a door open on one of our compactor site’s garbage bins would lead to the possible destruction of bear, might different decisions be made?

What exactly does it take for humans to literally clean up their act?

Hitting people in their pocket books is one way.

Zero tolerance with fines

The first black bear of the year was destroyed last week after a sub-adult bear broke into a series of homes in the Alpine neighbourhood. Two of the homes were occupied by residents, including the one where the bear was destroyed June 7. RCMP officers and the Conservation Office Service destroyed the bear out of concern for public safety.

"We believe the bear was responsible for other break-ins in Nicklaus North as well," said Rob Groeger, Whistler bear conservation officer. "We can link everything back to food of some sort. (We) were able to get within 10 feet of the bear. It had lost all fear of people completely."

The number of bear-human conflict reports received by the Conservation Office steadily increases every year in Whistler, mainly due to attractant issues drawing bears into human-habited spaces. While municipal bylaw and conservation officers have tackled the issue primarily through education, this year offenders failing to comply with garbage bylaws or the Dangerous Wildlife Protection Act will be fined without hesitation.

"We tend to use education as an effective tool," said municipal bylaw officer Sandra Smith. "You get a lot more than with a carrot than a stick, but we find we are not getting the cooperation we need and that’s why we are moving to zero tolerance. People should be expecting fines."

This heavy-handed approach stems from mounting concerns about public safety because of current bear activity. Along with home break-ins through open windows or doors, one bear tried to tear through the floor of a home from underneath to get at food.

"It becomes a severe public risk when bears are breaking into homes.

Something people need to be aware of is to make regular trips to dispose of their garbage. Don’t let odour build up. Bears have a super sense of smell," Groeger said, sharing a story of one incident where a bear caused $2,000 in damage to a car in a successful attempt to extract a muffin from the tail pipe.

"People should be aware of the fact that this is bear country. There are a lot of bears right now," he said.

Allen identified 37 bears in Whistler as of last week.

In 2005, the office received 17 calls for the month of June. Only halfway through June this year, more than 70 calls have been fielded, keeping the Conservation Office Service and RCMP running off their feet.

Garbage is at the source of most calls.

Mismanagement of garbage can be something as simple as leaving a bag of garbage outside, even for just a minute. Not storing recycling properly is also a problem, as bears will go after food-saturated containers and paper. Other common mismanagement issues include not closing bins at public compactor sites properly, cramming domestic garbage into Village Stroll garbage bins, overflowing commercial bins not being serviced enough, improperly used and managed strata company garbage sheds, and the list goes on and on.

Municipal fines run from $200 to $500, ranging from penalties for storing domestic garbage outside of a dwelling unit to not keeping wildlife containers in good repair or depositing commercial waste in domestic waste facilities – one of the biggest problems right now.

As a solution, the municipality is currently looking into installing video surveillance at the two compactor sites, allowing officials to monitor and fine offenders.

Bylaw officials are also working with Carney’s Waste Systems employees to identify problem areas. Already, the partnership has led to a number of referrals.

There is no bylaw against birdfeeders, so how do we keep residents in check when fines don’t bring about responses?

Not having to look farther back than his high school days, Brian Barnett, Whistler general manger of engineering and public works, said social pressure is far more effective than financial repercussions.

"Another element important to dealing with conflicts is social pressure," he said. "It’s a very successful tool and it is often more effective than financial penalties."

Social pressure pay-off

A community newspaper in Banff, Alberta exercised the premise of social pressure to mitigate attractant issues. The publication ran weekly updates on individuals or companies fined for mismanagement of garbage.

The program was short lived because of disgruntled advertisers, but even in businesses’ opposition, the reaction illustrated the incredible effect public opinion can have on issues.

Whistler has exercised public opinion on human-bear conflicts as well. The resort experienced a very busy 2004 bear season: the Conservation Office Service received 466 bear-related complaints and eight bears were destroyed.

"The Ministry got a lot of negative press for shooting the bears," said Tony Hamilton, environment ministry biologist. "Whistler said this is not acceptable anymore. Something needed to be done."

Public outcry resulted in swift action from Ministry of Environment officials who, with assistance from the Whistler Black Bear Working Group, initiated Canada’s first bear management study — the Whistler Black Bear Aversive Conditioning Research Project. A project dedicated to reducing the number of bears destroyed by teaching bears to stay out of public areas.

Like all relationships, it takes two and bears aren’t the only ones requiring education.

Education milestone

Whistler celebrates the 10 th anniversary of bear education in Whistler’s elementary schools this year.

Bear researcher Michael Allen runs a bear education program in both Whistler and Squamish. However, he is expanding his outreach province-wide next year.

"It’s a really good opportunity for Whistler to showcase the work we are doing with bears here," Allen said, adding Whistler still faces garbage issues. "The program is still in the initial stages."

After attending a B.C. Science Teacher Conference earlier this year, Allen said teachers showed interest in incorporating bear education into their science curriculums. As a result, Allen is currently seeking out sponsors to visit 30-odd schools from Vancouver Island all the way up to Prince Rupert next year.

"I can show kids across B.C. how bears live their lives here," Allen said. "I think that is what makes this program so intriguing. Kids get learn about bears through real-time information."

Watching Allen in action with one of the Grade 5 classes from Myrtle Philip earlier this month on Blackcomb Mountain, the success of the program was evident. Students’ bear knowledge was clearly evident. They easily rattled off answers to various bear smart questions, such as what to do in the case of a bear encounter or what steps residents and visitors alike need to take for peaceful co-existence.

Allen spoke with both passion and knowledge about his extended family — 40-plus bears in Whistler — keeping the group’s attention.

Along with showing kids a real bear den and branches of berry bushes (Whistler bears' main food source) not yet ripened, Allen talked about specific bears. How Max, the bear equivalent of a teenager, was chased off the mountain down to Whistler Village by a dominant adult bear. Kids wanted to know why. When faced with a tango between a 200-pound bear or a two-legged human, younger bears will often take the latter.

Students were excited to see two bears on the trip. All of the more than dozen students raised their hand when asked if they had encountered a bear before.

"My grandma had one come into her garage," one student said. "There was garbage inside. That was what the bear was trying to get at."

Students become the teachers, and parents and grandparents the students.

Better garbage management facilities

For Owen Carney, owner of Carney’s Waste Systems, creating the ultimate bear-proof bin is not so much about a final product, but a process. As one problem is solved another arises.

Meanwhile Sylvia Dolson, director of the Get Smart Bear Society, is lobbying for an entirely new system.

The difference between the two: costs and effectiveness.

Since 1979, Carney’s has serviced Whistler, both commercially for strata companies and businesses such as hotels and restaurants as well as publicly under contract with the Resort Municipality of Whistler to service the two public-use compactor sites: one in Function Junction, the other in Nester’s, as well as the now-closed landfill, and municipal hall and grounds.

Just when Whistler’s compactor sites appear to be working, bears up the ante of the situation, figuring out how to tackle over a bin or leverage a once bear-proof handle.

"As the years go by, the bears get smarter," Carney said. "We put the compactors in in 1979 and no bear opened it up until last year. We put a partial guard on it thinking we could fix it. But bears this spring are getting into it again, so we had to come up with another plan so that a bear can’t get its hand in, but the public can."

Bins need to be both bear and public friendly. Too bear-proof and the public can’t get in or won’t use the system properly. Too human-friendly and bears will break in.

The Function Junction compactor situation was corrected with a small steel gate earlier this month, protecting the long handle with enough space for a hand to access. The hand space for the leverage handle on the Village bear-proof public bins is smaller, yet still bears figured a way to get their paws in and pop them open – even when a lot of tourists can’t.

Also new last year was the addition of cement blocks to chain garbage bins down. Bears learned the benefits of dumpsters on wheels and figured out that by rolling them down a hill, the dumpster would over turn and spill out the contents.

"We are continually trying to keep up with bears as generations of bears teach their babies what they know," Carney said. "When we do something. They do something else. They are very clever and determined, so it is always a challenge."

This year Carney is beginning the process of refitting all of his bins, approximately 1,000 of them, with springs or bars to combat the tip and gorge problem. Commercial bins will be fitted with bars locked down with a carabiner — one of the few things bears still can’t open. The bar will have to be unlocked and slid from across the lids to access the bin. Carney said employees would require training. Such a set up is not public friendly, and therefore, springs will be implemented into latches for public bins. If the lid is spring loaded and the bin overturned, the lid will not open, Carney said.

"It won’t be done tomorrow," he said. "It’s a slow process, but we do it as we go."

The RMOW includes no bear-proofing stipulations in Carney’s contract. Barnett explained the responsibility lies with the property owners, not Carney’s.

"It is the owner of the garbage that is responsible for it," Barnett said.

Over the past 26 years, Carney said his company has spent more than a million dollars on bear-proofing tactics. The RMOW contract does not allocate any funds strictly for bear proofing. Carney has taken the steps on his own accord. He is also one of the members of Whistler’s Black Bear Working Group. In the late ‘90s, Carney worked with the group to devise an overhaul design for his bins. However, the retrofits keep happening year after year.

Almost for the same cost of all of Carney’s retrofits, Dolson suggests adopting a waste system in Whistler similar to the one used in Canmore.

"It’s proven highly effective," Dolson said of the Canmore system, noting bear destructions drastically dropped to only a handful of incidents after the system was adopted in the late ‘80s.

Instead of residents relying on two compactor sites, the new system would situate multiple bear-proof bins throughout Whistler neighbourhoods — approximately one bear-proof bin per 10 houses, requiring no longer than a two-minute walk to dispose garbage. The bins also include recycle compartments.

The Community Foundation of Whistler recently approved a partial grant for $6,100. Another $20,000 is needed to initiate a two-bin pilot project.

Allen stands behind Dolson’s proposal.

"Bears, people and garbage is not rocket science," he said. "Whistler needs to do it and follow the Canmore example. Pay the million or million and a half and get it done, so it is done. We can’t expect to just keep fixing the bins we have now. It’s not working… We are creating intelligent bears that keep learning how to get around them."

Garbage threatens study success

You can chase them away with rubber bullets, but the call of a food-soaked pizza box in a recycle bin keeps luring black bears into Whistler Village, a Whistler research group reports after the preliminary year of a three-year study.

The Whistler Bear Aversive Conditioning Research Project explores alternative ways to reduce human-bear conflicts by studying the effectiveness of non-lethal aversive conditioning practices on bears infringing on public spaces. The findings will establish bear management guidelines for the rest of B.C. as well as potentially North America.

Preliminary results collected in 2005 revealed problematic attractant issues, mainly mismanaged garbage. Research radio collars used to track unruly bears instead led the team on a garbage wild goose chase.

Bears climbed onto rooftops to lick grease from restaurant fans and one bear even ingested three unattended 12-packs of beer.

As one researcher put it, unless attractants are controlled, trying to teach a bear not to come into a public area is like putting a kid in front of a candy store and telling them not to go in and eat.

"Driven by the number of calories the bears need to consume every day if you have a choice between an apple and a Big Mac, and you are starving, what are you going to chose?" said study researcher Nicola Brabyn .

"Bears can’t have access to garbage. It’s vital to the success of doing aversive conditioning."

The study team of Hamilton, Brabyn, researcher Lori Homstol and municipal bear officer Rob Greoeger collared 14 bears with radio locaters in July 2005. Bears were then monitored and reprimanded if they entered the no-go zone —public areas including the base of Blackcomb Mountain, Whistler Village and Creekside Village.

Combinations of rubber bullets, noisemakers and/or beanbags were used to scare bears away along with aggressive human posturing and yelling.

Hazing, a single immediate action to move a bear away from conflict, was the primary tactic used in the study’s first year. However, researchers now use more aversive conditioning tactics, a practice whereby researchers follow a bear and apply a consistent application of deterrents ideally until the undesired behavior is broken.

"Slip (one of the study’s bears) will get some intensive work for ten days," Hamilton said. "We are not going to use rubber bullets and noise makers again, we want to try human dominance on him and literally stay on his butt, so we are saying we are the bigger bears and this is the core area and you are not welcome in it."

Despite 341 bear-related complaints, no bears were destroyed due to human-bear conflicts in the 2005 season thanks in part to a plentiful berry season that kept bears feeding outside of the Village and the additional manpower the study and new bear officer provided.

Greoger said the zero kill statistic was misleading in suggesting Whistler is free from bear-human-conflict problems.

"If attractants continue to be available, we aren’t going to get there," Hamilton said. "The more (bears) get rewarded. The harder those habits are to break… It’s going to be more difficult if attractants remain available, but we have had enough success to carry on."

The study has produced some amazing findings. Researchers discovered some bears are using human company to shield themselves from other bears. Hamilton questions whether human habituation can be site specific, basically teaching bears to avoid particular sites without effecting habitation elsewhere.

The study is also looking at whether it is possible to work with certain bears who dwell on the border of human areas. Hamilton said adult bears hold the perimeter, keeping yearlings and sub-adult bears away from the public. He used the example of Patch who hangs around the backside of the Blueberry neighbourhood. Patch has exhibited problematic behavior such as rolling garbage bins down the hill.

"If we could break him of the behavior, but have him still occupy the landscape, the sub adult males (wouldn’t come into the area)," Hamilton said. "In the past those animals would be shot and we lose our resident animals."

Community solution

All officials interviewed — educators, researchers, biologists, activists, business owners and government officials — agreed on three things: one, that educating the public is crucial to the success of bears and humans peacefully co-existing; two, that Whistler faces ongoing garbage management problems; and lastly, and most importantly, that officials can have all the tools, laws and staff in the world, but ultimately, the power lies with the people who live and visit here, and the decisions they make.

The decision to rinse recyclables, to close a lid, to take down a bird feeder. The decision to report mismanaged garbage, to educate employees, to scare a bear away from a yard rather than watch it: all of these seemingly small actions make a difference — possibly a lifesaving one.

"One thing I teach the kids is that if the environment is healthy for bears, it’s healthy for us," Allen said.

"We want to try to have Whistler as bear-proof as possible, but at the end of the day, the public has to be responsible — we can only do so much," Carney said.

"If we educate the public on what the potential risks are of not disposing of garbage properly, maybe that will help," Smith said.

"(The bears) have figured out our uniforms. Slip was in town today outside of the Brewhouse and as soon as I got out of the truck and saw me, he headed out into Lot 1/9. These are very, very smart animals. People don’t give them enough credit for that," Groeger said.

"Tolerance is wonderful, but it’s harming the bears because people are not calling when bears are getting into garbage," Brabyn said.

To report a bear-human conflict, mismanagement of garbage violation or collared bear sighting, call 1-877-7277.

For more information on Bear Smart practices, visit www.getbearsmart.com .