When Paul Mathews of Whistler-based Ecosign Mountain Resort Planners first visited Russia in the late '90s to investigate potential ski areas for the brave, new post-Soviet nation, his head was filled with the typical clichés.

"When I first went there I was quite scared, because of the propaganda I've received growing up in North America. I had a lot of trepidation," Paul said in a 2003 Pique article, "The Russian Front."

But, true to another cliché, reality proved different for the seasoned ski resort planner, who went on to pinpoint, plan, then oversee the building of Krasnaya Polyana near Sochi as the place for Olympic alpine skiing and snowboarding.

"When I got there I was looking for mafia and military and bread lines and fat, ugly people, and what I found was quite... I was quite embarrassed by my perception of Russia and the reality of it. I really felt like an idiot."

As the 2014 Winter Games unfold at Sochi (really, at a small coastal city southeast of Sochi called Adler, where the airport and all the ice rinks are, and at Krasnaya Polyana further inland for the alpine events), you'd be forgiven for picturing ever more clichés when it to comes to food.

Yes, there's borscht, beets and blinis, says Paul and fellow Whistlerite, Roger McCarthy, who oversaw the building of the alpine event facilities at Krasnaya Polyana. But there's a whole lot more.

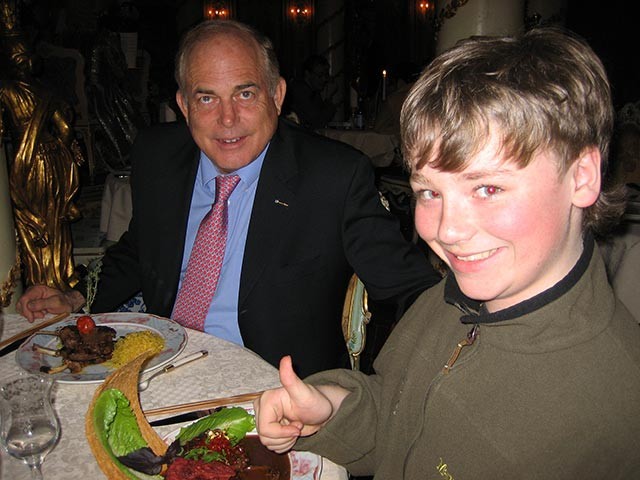

You can have a burger at the American Diner in Sochi or a burrito at La Cantina, a Mexican restaurant near Red Square in Moscow. You can make your way through a multi-course meal at a Louis XIV-style restaurant replete with a giant gold peacock, chamber music and servers in courtly wigs and dress. You can dine at a spectacular seafood restaurant with a glass floor. The fish, which you're about to choose from to eat, swim about under your feet.

That's how the brave new oligarchs and VIPs like Paul and Roger dine in Russia. And even though the gap between rich and poor there continually narrows, it's still striking.

"The polarity of wealth is absolutely astounding," says Roger, pointing out that frugal tree cutters who cleared the forests at Krasnaya Polyana would hang up their teabags to dry so they could reuse them. "You are constantly reminded of it." By the plethora of armoured Mercedes and Maybachs that go for US$300,000–$400,000, by the many high-heeled "girlfriends" mincing about the power brokers, by the wild boar picnics in the middle of nowhere.

A highlight of one of Paul's working visits when he was accompanied by dignitaries like Boris Berezovsky, a mathematician and then a member of the Duma for the North Caucasus who made headlines when he died of poisoning last summer, was an elegant picnic for about 30, complete with white table linen, and anything you wanted to drink, of course, all flown in by chopper. Wild boars were roasted on spits, while armed bodyguards roamed the forest. And when the meal was done, one of the federation presidents tore the ears from a boar's head and gave them to Paul so he could listen to his mentors and write a good technical report.

"It's all true!" says Paul with a laugh. And just one of the many dining surprises.

Paul and Roger were delighted to find so many fresh fruits and vegetables, putting the lie to bread lines and borscht. Available year-round, the veggies were served as side dishes, often cooked to perfection ("crunchy"); in delicious, clear-broth soups; or maybe as a refreshing salad called shopska, traditionally from Bulgaria.

Both reckon the fresh produce comes from Georgia, just to the south of Sochi, which is located at about the same latitude as central Oregon and only an hour's flight across the Black Sea from Istanbul.

And while lamb kebobs, or shashliks, were Paul's most trustworthy quick bite, Roger would go for an apple or a sandwich as an antidote to the heavy meat-and-potato working meals, often prepared by a cook on-site, whether at the office or on a construction site.

"The Caucasas are different — better, I think," says Paul, pointing to the Cossack tradition of welcoming strangers into your tent for a meal, a common custom amongst nomadic peoples.

"The waiters and waitresses smile in Sochi. They don't in Moscow..."

Glenda Bartosh is an award-winning journalist who one day wants to swim in the Black Sea.

A TOUCH OF RUSSIA AT EVERY TABLE

No matter what clichés we hold about Russia, virtually all of us in the West are deeply familiar with at least one Russian tradition. Every time we eat in a restaurant or have a sit-down meal, how we set the table and serve the food has come to us from Russia.

Russian service, or service à la russe, as any good butler will tell you, is a formal elegant meal service, but one less complicated, faster and more to the point than the classic French style it supplanted.

According to Larousse Gastronomique, French service ruled during France's great First and Second Empires, especially in Europe's "great houses" of the day. Starting in the grand court of Louis XIV, which pretty much says it all, it was delivered, literally, by a small army of servants at great cost and extravagance.

Ostentation was the name of the game. A French service meal had three distinct rounds with as many as eight entrees and multiple cold and side dishes. All of the dishes for the first round of service — the mousses, the aspics, the pâtés, cheeses and fruits; even the main courses — were arranged on the table before the guests sat down, just like Paul and Roger experienced at many of their meals in Russia. That, and their "golden peacock" restaurant experience, replete with chamber music and musicians and servers dressed like Louis XIV courtiers, suggests that the haute monde of Russia, in the throes of their latest empire, are dredging up the golden age of France in pursuit of the exotic.

These days, classic Russian service — popularized beyond Russia's borders around 1860 by the French chef, Urbain Dubois — is pretty much the norm around the world for serving meals and organizing menus. Dishes are served in a certain order — appetizers, soups, salads, the main course and so on — with most of the prep work is done in the kitchen. Only the meat might be carved at the table.

Guests help themselves or, if a maid or waitperson is handy, are served. Dishes are offered on the left-hand side; wine on the right. Plates are put down and taken away on the right. Everything is aimed at keeping the food piping hot and, ironically, at minimizing "useless ornamentation and vulgar decoration."