Stretching 1,800 km from Hangzhou in the south to Beijing in the north, China's Grand Canal is the longest man-made waterway in the world. It took a very long time to build, but then the fellows who dug it didn't have backhoes or dump trucks. In fact they didn't even have decent wheelbarrows and shovels — but what they lacked in tools they made up for in numbers.

More than six million peasants were conscripted to toil on the project and working conditions were so bad that an estimated 50 per cent of them died on the job. But it's unlikely that Yangdi, second emperor of the Sui Dynasty, was troubled by such details as he sailed triumphantly into Beijing in 611 AD.

On his first voyage, Emperor Yangdi, aboard the ornately carved, four-deck royal barge, led a procession of a thousand lesser craft carrying members of the court. Eighty-thousand coolies, assisted by "the loveliest girls in the empire," were conscripted to haul the procession upstream. Forty new palaces were built on the banks of the canal for overnight accommodation. The Emperor so enjoyed the trip he organized others but, perhaps understandably, his enthusiasm was not widely shared.

On his third excursion Yangdi was hung by disgruntled members of his own crew.

Yangdi's death in 618 marked the end of the short-lived Sui Dynasty but not of his canal. The original scattering of ditches was linked together. Wiers, dams and levees were built, channels were deepened and widened, boat-locks and a hand-powered ship-lifting winch were installed. By 1271, when the Yuan Dynasty under Kublai Khan moved the capital to Beijing the Grand Imperial Canal was a busy transportation corridor providing a vital link between the fertile rice-producing areas of the Yangtze estuary in the south and the densely populated but barren lands of the north. For the next six centuries the canal funneled an astonishing tonnage of freight from the farms and factories of the Yangtze lowlands north to Beijing. Ten-thousand rice barges were joined on the canal by other ships carrying salt, cloth, bamboo, and timber — and, of course silk for the emperor and his court. Even the bricks in the Forbidden City and the Ming Tombs came up the Grand Canal.

When the railway took over in 1902 long distance canal transport was officially abandoned but segments of the old waterway are still used for local shipping. Between Hangzhou and Suzhou the canal and its myriad interconnected waterways is not only the main supply artery for the farms and factories that radiate out from Shanghai, it has also become a major tourist attraction. We could have taken a passenger boat between the two cities but we opted instead to explore some of the lesser towns and waterways along the way.

In Hangzhou, the southern terminus of the Grand Canal, we joined a happy throng of vacationing locals for a tour of West Lake. Surrounded by forested hills this small lake in the very centre of town has been described as “a landscape composed by a painter.” A classic Chinese pagoda stands atop one of the hills and, from the lake the busy streets of Hangzhou are screened by parkland. After our boat tour we followed a broad walkway along the shore past temples and pavilions to a small open-air teahouse, where we sat and watched a wedding party. As a honeymoon destination Hangzhou is China’s answer to Niagara Falls. Its reputation goes back to the Song Dynasty when Marco Polo described it as a place “where so many pleasures may be found that one fancies oneself to be in paradise”.

From Hangzcou to Suzhou the Grand Canal crosses the very heartland of China’s “rice bowl.” The channel is crowded with barges laden with bricks, scrap metal, and other raw material for the factories lining its banks. The land is flat and laced with a labyrinth of channels, ponds and levees — rice paddies, fish farms, market gardens, and large ponds where fresh-water-oysters are grown for their exotic pearls. The highway, only two years old, winds back and forth across the canal and through a succession of “water-towns” where old neighbourhoods are giving way to apartment complexes and sprawling industrial development. The canal and its network of waterways opened China’s “rice bowl” to the country and provided the basis of a unified national economy. But it brought with it urban expansion and industrial pollution.

As we approach Suzhou the farms become smaller and fewer, the factories bigger and more numerous. Clusters of attractive houses, the new homes of farmers displaced from their fields, sprawl across the landscape. Our local guide explains that the farmers have been well paid for their land and are happy with their new homes. However, stories of protest against the expropriation of land are rampant and a recent study estimates that 10 per cent of China’s arable land has already been fouled by industrial and urban waste.

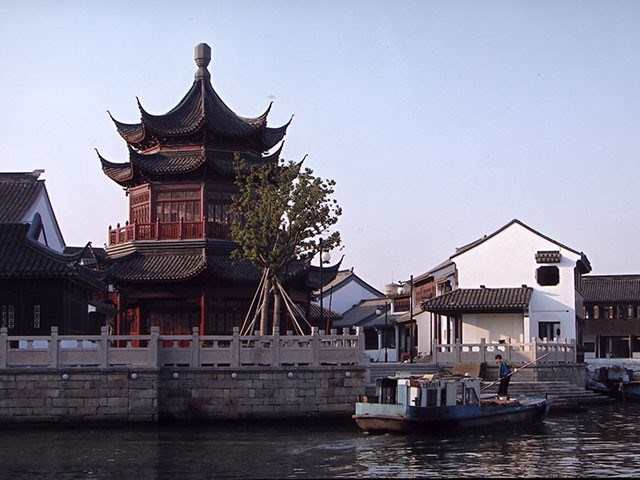

Despite the encroachment of industrial blight, Suzhou remains one of the greenest and most beautiful cities in China. The moated city of Old Suzhou is now a protected historic district. With an area of 15 square kilometres it is one of the few places in China where high rises and factories are excluded. We spent an entire morning exploring its classic gardens and scenic waterways before moving on to the Museum of Suzhou Embroidery. It was silk, not gardens that first put Suzhou on the map of China. For centuries its artisans have excelled in the art of silk production and embroidery. And it was access to silk, no less than to rice, that inspired Emperor Yangdi to dig the Grand Canal.

I was surprised to see what I took to be a large photograph of Chairman Mao over the entrance to the museum. In fact it was a demonstration of silk embroidery, a likeness of Mao’s familiar visage made with needles and thread so fine that the stitches are like the pixels of a high-resolution colour photograph.

The museum is a working factory that traces the production and marketing of silk from worms feeding on mulberry leaves to long-limbed models strutting on a fashion runway. We followed the plump white cocoons as they trundled down conveyor belts through the sorting room and on to the spinning machines. Finally in the embroidery room we watched the young women who turn the silk thread into elaborate works of art. Like the tailors in Hans Christian Anderson’s tale of “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” the women seem to be working with invisible needles and thread. They give their eyes a 10-minute rest every two hours and it may take months or even years to complete one of the more complex pieces. But all is not well with the silk industry.

For thousands of years silk farmers have fed their worms mulberry leaves and harvested their cocoons for sale to the factory. But in recent years many worms spin only a token cocoon or no cocoon at all. “The problem,” explains our guide, “is believed to be pollution. Toxic chemicals on the leaves are making the worms sick. But,” she adds confidently, “the government is committed to solving the problem.” Perhaps, I thought, the silk industry is still important enough to China’s ruling elite that something will actually be done. But reversing the present trend to bigger industry at the expense of agriculture and the environment will be a task as daunting today as digging the Grand Canal was 2,000 years ago.