O ho Canada! Excellent birthday party last weekend. I've never seen so much red and white all at once! Given the excitement, it only seems right to keep the 150 ball rolling and have some fun at the food end of things in Canada round the time of Confederation, and beyond.

Courtesy of Alison Pascal at the Squamish Lil'wat Cultural Centre, last week we enjoyed a sampling of some of the traditional foods indigenous peoples around Whistler have enjoyed over time — from moose and marmot to fresh trout and duck; salmon and salmonberries; root veggies, and more.

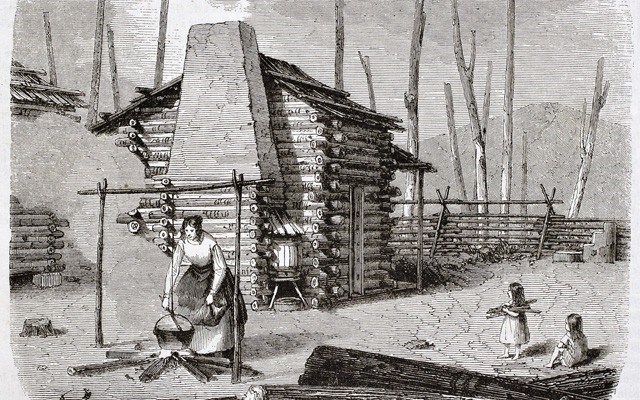

Thanks to the knowledge of indigenous people from coast to coast to coast, early pioneers also counted on food that could be hunted, fished or gathered from forests, fields, lakes and streams, and the great oceans where possible. They also grew what they could — mostly beans, squash and corn — to add to the venison, bison and dried salmon; the wild fruits and vegetables.

Around 1867, many people ate like that as they eked out a living on the land. But if you look through records of early settlers around Whistler, you get a similar sense of things even though it was decades later. Certainly beaver tails were beaver tails, nothing to do with pastry cinnamon.

One early Whistler pioneer was John Millar, namesake of Millar's Creek. A trapper from Texas, supposedly with a checkered past and no doubt a checkered tablecloth, he served up a mean muskrat stew and Steller's jay pie.

Alex and Myrtle Philip left a bigger mark on Whistler's culinary history after they opened Rainbow Lodge on Alta Lake. The lodge was all about the fishing, and besides sizzling trout cooked over an open fire, the Philips were known for serving up a wicked wild blackberry pie and roast chicken with potatoes.

But there was definitely another side to Canadian cookery around the time of Confederation, as former Chatelaine columnist and General Foods publicist Una Abrahamson points out in her wonderful book, God Bless Our Home: Domestic Life in Nineteenth Century Canada.

If you like to know your subject material is well researched, you have to hand it to Ms. Abrahamson. She passed away in 1999, but not before amassing a huge collection of books on a wide range of domestic topics, from food, health and nutrition to table manners, alternative medicines, and social histories. The collection, which dates back to the 17th century and includes more than 2,700 books, now resides at the University of Guelph. Abrahamson was also a popular lecturer, regaining her ability to speak and write after spending more than a year in a coma as a result of being struck by a car.

So what else were 19th century Canadians eating and drinking, besides wild game and home-brewed hooch? Just grab a copy of God Bless Our Home and you'll be amazed.

The book, which was first published in time for Canada's last big birthday bash and Expo 67 — our 100th anniversary of Confederation, as Bobby Gimby's hit song declared — is as much a celebration of the nation on the grand scale as it is on the domestic one. "The Dinner Question" chapter points out just how varied our Canada diet was. It still is.

"Tracing our culinary tradition is fascinating because the history of cooking in Canada is complex, and, so far, almost unrecorded," writes Abrahamson. "Food ranged from basic porridges and stews to the sophisticated dinners of the gentry based on Hannah Glasse and Isabella Beeton's research." (That would be Mrs. Beeton herself, the eldest in a family of 21 brothers, sisters, half-sisters and more, and author of Mrs. Beeton's Book of Household Management, widely regarded as the greatest cookery book in English, first published as monthly supplements in England between 1859 and 1861.)

"This variant existed throughout the century," continues Abrahamson. "While some families in eastern towns were enjoying imported luxuries, other families pioneering in the west were eating the staple salt-rising bread, bannock, and slapjacks (griddle or pan cakes), which the east had known a hundred years earlier."

She goes on to point out that much like at Whistler, people often continued to eat what you'd call a pioneer diet, "which was often heavy, usually greasy but generally sustaining and frugal" and largely influenced by indigenous foods, long after city denizens and grand folk had moved on to grander things. Ideas, recipes and products poured in from migrants from the U.S. as much as they did from England and the rest of Europe.

The British advised how to make things like Regent's punch, with its green tea, "pine-apple" syrup, Seville oranges and Jamaican rum or Prince Albert Pudding, heavy on the cream and sponge cake. For those with tighter budgets, there was mock mince pie made with soda crackers and mock lobster from seasoned cold veal. Even pigeon pie was popular.

Germans brought spiced meats, sauerkraut, waffles, applecake, pies with crumb toppings, gingerbread and that ultimate Canadian snack — doughnuts. The French preserved and adapted the country cooking of the thrifty people from the coastal regions of northern France — tourtière or meat pie; soups made with dried peas and beans; pork with apple and cinnamon.

To this list we can now add the joys of cooking from China, India, Japan, Iran, Syria, Nepal, Palestine, Nigeria, Mexico, and more.

I bet if we started counting now and we do it altogether, we'd find 150 cuisines interwoven into the food we call Canada — and all of it worth a second helping, please.

Glenda Bartosh is an award-winning journalist who likes to branch out in the cooking department.