When the bad weather came, Ernest and Hadley left Paris for a place where the rain turns to snow sifting through the pines and covers the roads and high passes.

The Hemingways took the train from Gare de l'Est to Buchs in Switzerland then on to Austria, changing in Bludenz for Schruns, where they spent the winter and Ernest wrote and Hadley played piano and they both skied as much as they could. The Montafon Valley here was wide and there was good sun, but the shadows fell fast and they could hear the snow creak as they walked home at night in the cold with their skis on their shoulders watching the lights of town approach until their beloved Hotel Taube appeared with its big windows and big beds.

The Hemingways were fond of the practice slope behind the Taube where you ran down through orchards below Bartholomaberg. Another pitch in back of the village of Tschagguns across the valley led to a fine inn with chamois horns on the walls, where there was always wine and beer and local kirsch. Above Tschagguns, the really good skiing went all the way up onto the glaciers until you crossed the Silvretta into Switzerland.

Herr Walther Lent, a pioneer high-mountain skier and onetime partner with the great Arlberg skier Hannes Schneider, had a school for alpine skiing in Schruns that Ernest and Hadley enrolled in. Ernest relished Lent's system of getting pupils into the high mountains as soon as possible. He also enjoyed that anything you ran down you had to ascend. No one minded climbing then, because it was fun and gave you legs fit to run down on and your heart felt good and you were proud of the weight of your rucksack.

Lent may have been Austria's first freeskier, but Hemingway, certainly, was the country's first American ski bum. You get the idea from his writing in The Snows of Kilimanjaro and A Moveable Feast—perhaps even from the cadence of my paraphrasing—that Austria was a place for the brave and courageous and dedicated. A place of surpassing authenticity. And that this was the way it should be.

A century later, authenticity still rules the world's only de facto Ski Nation State. Changes which long ago swept most alpine countries—ski-area amalgamation, doorstep skiing, park and pipe proliferation, resortification—are just now reaching into the deeper nooks of a country boasting some 300 ski areas. Austria is also stepping beyond its racing vibe to reassert itself as the destination it relinquished to the French in the 1970s, a haven where growing ranks of ski bums—always somewhat out of sight here—now quietly proliferate without the self-congratulating ball-grab of a Chamonix, Verbier or Engelberg. Thus, despite its unassailable ski heritage, Austria remains a sleeping giant for freeskiers and seekers of freedom alike. A virtual Republic of Skiing—spontaneous and timeless in the same instant.

Hemingway's Montafon has likewise evolved, as seen in the recent ski-area mega-amalgamation of Silvretta-Hochjoch spanning both sides of the valley. But Montafon's intersection of occasional modernity and coddled posterity is still on display at Gargellan ski area, whose lower-mountain clusters of open-sided stables, musty barns, and sagging restaurants (none of which accept the contemporary convenience of credit cards) recall the medieval winterscape of Brueghel's The Hunters in the Snow—reinforced by the frequent smell of manure.

Some things, of course, resist change. If you want to make a ski tour up to Wiesbadener Hutte in the Silvretta Range around Piz Buin, the region's highest peak at 3,312 metres, you now start your day in a most modern way: a brand new aerial tramway whisks you to the top, and from there a van drives you 10 kilometres or so through a series of austere tunnels to the edge of Silvretta Reservoir—now a summer hiking destination—where you finally slap on your skis or snowshoes. As you head out across the mountains, you pass timeless Silvretta-Haus, Gasthaus Piz Buin and venerable Madlenerhaus, the hut Hemingway once spent all day touring up to and romanticizing in many a story.

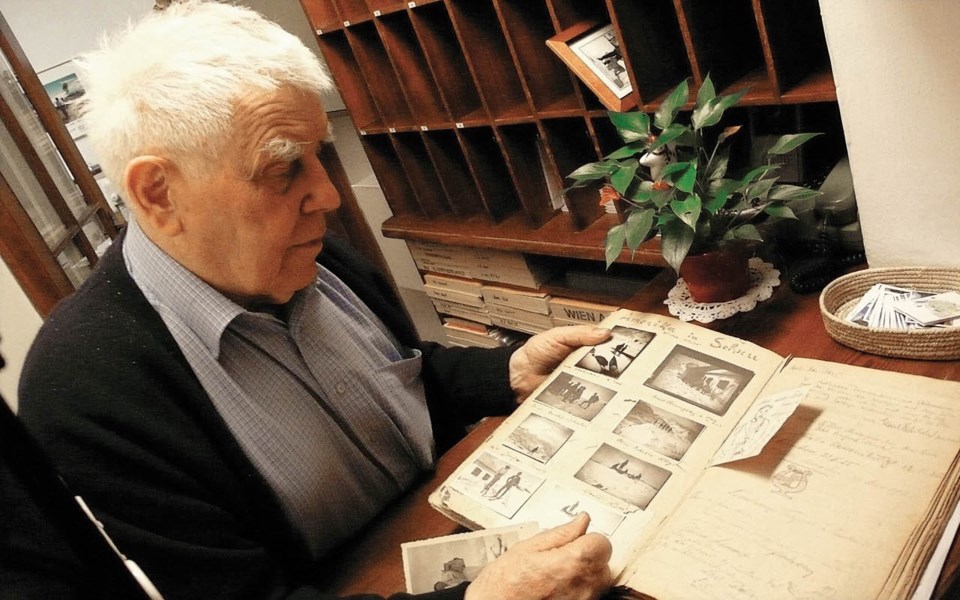

Back in the valley, Schruns' Hotel Taube, where Ernest and Hadley lived, also returns you to those halcyon art-deco days with its halfmoon doorways, brass locks, porcelain sinks and oddly sculpted urinals. The desk clerk may have been a child when Papa H. lived in his family's hotel, but his sharp recall of the man is aided by the stories his parents told and a scrapbook of cracked, sepia photos of Hemingway outside the hotel drinking with his buddies while their hickory skis with dangling leather bindings leaned against the wall. Walking through the hotel today, you aim for the quiet of reverence it seems to demand, but the Taube's ghosts will have none of it. The floorboards creak out short, unpunctuated sentences while the sounds of a raucous, back-slapping kirsch party rise up the stairs from the bar—the loudest voice of all, you imagine, Hemingway himself.