The game is “Sarajevo Roulette.”

The players are ordinary, unwitting Bosnian civilians who go

about their daily lives, collecting bread and water amidst a war-torn urban

battlefield during the siege of Sarajevo, the longest siege in the history of

modern war. They are pawns in a dangerous game, and to win it, all they have to

do is survive against the falling shells and the whizzing bullets that come

from snipers on the surrounding hills.

Every day, however, there is a moment of pause for the people

of Sarajevo. A cellist descends the staircase of a crumbling building. Bow in

hand, dressed as though ready to take the stage at Carnegie Hall, he plays

Albinoni’s Adagio every afternoon for 22 days — one for every life lost

when a mortar fell on people waiting in a bread line. For a few short minutes

each day, the people of Sarajevo get some respite from the chaos and carnage

around them.

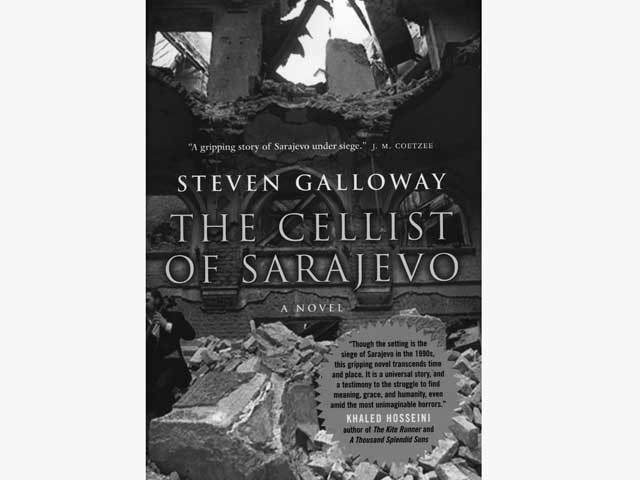

It’s against this backdrop that Canadian author Steven

Galloway’s The Cellist of Sarajevo unfolds — an elegiac tale of survival

against a daily barrage of death coming from all sides.

The story itself unfolds on three planes, all of them revolving

in some way around the cellist. The most compelling is that of “Arrow,” a

female sniper whose job it is to keep the cellist alive; there’s also Kenan,

who makes a regular trip to get water for his family and who has scant moments

of happiness when the power flickers on at his home; and then there’s Dragan, a

baker who no longer recognizes his own city.

Galloway has been something of an unknown outside literary

circles up to now. A professor of creative writing at both the University of

British Columbia and Simon Fraser University, he got favourable reviews for his

first two books, Ascension and Finnie Walsh, but has achieved a much higher

profile with this one.

Critics have lavished the book with praise and Galloway

recently sold the foreign rights to 18 countries for $18 million.

The wide-ranging appeal of his novel could have much to do with

the deftness with which he puts a human face on war. All the central characters

are forced by the siege into challenging their strongest beliefs and

assumptions.

Arrow the sniper, for example, starts to have moments of

hesitation as she gets her targets in her scope sights. In one instance she’s

locked on, ready to kill one of her enemies, but has a moment of pause when she

starts to hear the cellist playing. She keeps her guard on, an enemy sniper in

her sights, but waits until the end of the Adagio before she snaps back to

reality and takes her shot.

Then there’s Kenan, who in addition to providing water for his

family finds himself reluctantly doing the same task for a cranky neighbour in

his apartment building. He can’t stand the sound or the sight of her, but war

pushes him to do a humanitarian task even for someone he knows he can’t stand.

Though the story itself is fragmented, unfolding in a sometimes

jolting fashion along three different narrative lines, Galloway communicates

his characters through an involving, lyrical writing style that jumps back and

forth between past and present. The reader is slowly drawn in to the

experiences of the characters and learns quickly how much their lives have

changed between the pre-war and post-war periods.

But the most effective device in the novel is its subtlety.

Galloway has remarkable success by taking the political out of the story. Not a

single one of the characters is identified by their ethnicity — they

could just as easily be Bosnian Serbs as people loyal to Yugoslavia. But you

never really know, and that very device maximizes the sympathy that the reader

feels for the characters — and civilians on both sides, really, are the ones

embroiled in the war.

In short, The Cellist of Sarajevo is a novel filled with heart, compassion and lyrical narration. Together with Rawi Hage’s De Niro’s Game it’s one of the best Canadian novels of recent years and is near certain to be cited come the season for literary prizes. It’s near-poetry.