Tourism may be the bread and butter of Whistler, but there is another industry that could perhaps be described as its backbone these past 40 years — construction.

It has been transformative, revolutionary, cutting edge, and a multi-million dollar industry that has kept hundreds of community residents busy over the years, and still to this day.

This small valley of lakes, dotted with a few rustic cabins and old lumber camps, has grown into a town of award-winning architecture.

And as the architecture has morphed from basic A-Frame cabins and Gothic Arches to contemporary avant-garde works of art in themselves, so too have the local builders.

"Construction has always been and will continue to be a key economic conduit in this community," says Chris Addario, president of the Whistler Chapter of the Canadian Home Builders Association.

"If and when someone invests in our town and hires one of us to build, renovate or repair their home we then distribute a portion of that money throughout our community in particular by employing locals. A lot of the money they earn is spent around town, which in turn provides jobs and opportunity for others."

While many builders have come and gone over the years, a few like Glen Lynskey, Matheo Dürfeld and Andy Munster have stayed the course right from the beginning.

They came in the early days, more often than not, just to ski. And building homes became their ticket for doing just that.

But it became more than that.

They discovered they were truly talented at the job, up for the challenge, able to improve and get more refined and willing to evolve.

That typical eight-month building window from April to December began to stretch into multi-year projects as the builds became bigger, more complex.

"Nobody came here with all that expertise," says Dürfeld. "That expertise grew and developed here."

In this first of an ongoing and occasional series of articles on the Whistler building industry, Pique examines the legacy of Lynskey, the evolution of Dürfeld, and the tradition of Munster. In the coming months Pique will be looking at the Whistler construction industry in a series of features running from green building, to award winning builders to the all-time top sellers.

Perhaps the trade has been quiet in recent years as the world's recession came to the mountains too. Perhaps customers have been worried about the bottom line, more value conscious than in years past.

But you'd never guess it stepping into the latest homes of these three Whistler builders.

Their stories, in a way, mirror the story of Whistler.

It's about coming of age; about seizing unbelievable opportunities; about welcoming the world in a laid-back, laissez faire way; about becoming the best, but with a quiet, almost humble air.

The Legacy of Glen Lynskey

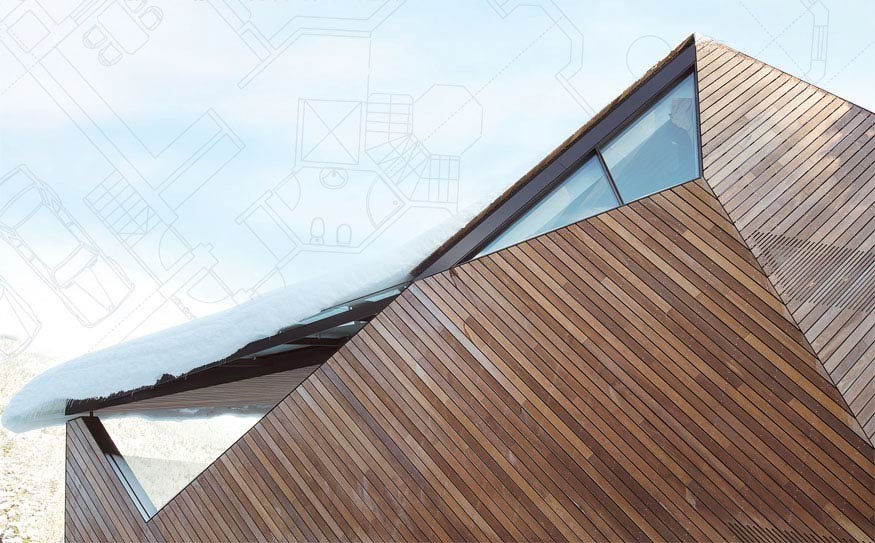

The "Origami House", as it's come to be known, will be called many things in its lifetime — a geometrical conundrum, a theatrical statement of architecture.

It could also be called Glen Lynskey's swan song — for it is a home he will never see finished. In a tragic turn of events Lynskey died suddenly last fall after complications from a fall on his bike.

He was 60 years old and arguably at the top of his professional game.

The "Origami House" in many ways is his ode to taking chances, to bucking convention, to living, quite literally, on the edge.

It is a symbol of what building in Whistler has become to some extent — state of the art, limitless, fearless — and the possibilities of where it may go in the future.

Like Lynskey, the house is undoubtedly unique, seemingly defying gravity, certainly defying convention, hanging off the side of a cliff in Sunridge.

It was designed by the award-winning Canadian firm, Patkau Architects, who were charged with using their imagination.

Owner Martin Hadaway, who lives in Hong Kong, knew Lynskey was the man for his job as soon as he met him.

"We warmed to him immediately as he was a calm experienced guy with an excellent track record whose honesty and integrity shone through," he says. "Our house became a labour of love for all of us."

Since Lynskey's death his crew, one of the biggest and most loyal in the local industry, has been carrying on, finishing up the four, multi-million dollar builds Glen left behind.

His legacy, however, lives on not just in the "Origami House" but also in the more than 40 houses he built throughout Whistler.

And while most don't have the immediate reaction of the "Origami House," many of them have qualities that speak to the uniqueness of the unconventional builder himself.

When other builders talk of him it's in a somewhat reverential way; he was a master craftsman with an old school approach.

Take a house in Alpine, one of Glen's first homes that he designed in the early 80s. It looks like any other old ski chalet — peaked roofs to shed the snow, wood siding, a silver pipe for the wood burning stove rising up toward the sky.

But take a closer look and there's something a little different about this house — the roof seems to bend and curve. It's almost as though your mind is playing a trick on you. It's a hyperbolic parabola, like a saddle, or a Pringles chip. Not your typical roof. And not what you expect to find in an old ski cabin.

What you can't see from the outside is another architectural feat within; the house is designed on the Fibonacci mathematical sequence — 1+1=2, 1+2=3, 2+3=5, 5+3=8, and so on. That same mathematical sequence found throughout nature — the arrangement of leaves on a stem, the flowering of artichoke, the arrangement of a pinecone, the shell of a snail.

Such was the mind of Lynskey.

"It was always about the challenge," says Lynskey's wife Heather. "Otherwise, he was bored."

Lynskey was gifted, his intelligence pegged at an early age at school in Toronto. He quickly moved into gifted programs and ended up with a BA in history from the University of Toronto.

He also loved to ski, couldn't be enticed away from the hills when he was a boy. And that's how he ended up in Whistler in 1971.

Tree planting and building were the order of the day in Whistler at that time. Getting into construction meant he had the winters off to ski and also meant he could exercise his mind too.

Within a decade he had incorporated Alta Lake Lumber and was making his mark in residential homebuilding as new subdivisions began to spring up in Whistler seemingly overnight.

Lynskey always wanted to be an architect says Heather. He designed houses in the early days, including his own, complete with two-storey concrete walls.

Heather remembers what people were saying to her at the time: "Don't let him do it — he's nuts!"

Crazy? Hardly. A visionary, never one to shy away from testing the boundaries? Truly.

As the world began coming to Whistler, using architects became the norm, particularly as the homes stretched into the multi-million dollar range and with that, increasing complexity.

"A lot of people gave him chances based on just talking to him," says Heather.

In 2008 Alta Lake Lumber was named a finalist in the Canadian Home Builders' Association's annual Georgie awards, honouring excellence in construction and design in B.C. It was the first time they had ever entered the awards, says Heather.

It would be hard for Lynskey to pick a favourite says Heather but one was close to his heart — The house is in Horstman Estates, a four-year build, another labour of love.

Down at Lakecrest Lane, Lynskey's black pick-up truck is parked outside another big build on the lake. His crew is hard at work, pouring concrete today.

It's for two side-by-side lots for a family home that stretches across the lake. One building for the home — bedrooms, kitchen, living area. The other building for a home office and studio, gym and spa.

Lynskey's right-hand man, Brian Gavan, who is in talks with Heather to take over Alta Lake Lumber, says they are working not just on finishing up the ongoing projects but securing new ones for the future too.

"We've got some irons in the fire," he says.

His comments are tinged with sadness the more he talks about Lynskey, the man who took a chance on him, mentored him over the years, his friend.

It's one of the things that perhaps people didn't know about Lynskey, says Heather.

At his core he was a kind person, always sensitive about how people felt.

"He was a really caring person," she says.

Then again, perhaps they do know. Many local contractors got their start at Alta Lake Lumber. Lynskey took many a chance on a 19-year-old kid, helped them, and let them go when it was time for them to forge their own way in the industry.

Heather hopes his legacy won't just be his houses but that Alta Lake Lumber carries on too without him.

"Just to think of it ending... that's 30 guys out of work," says Heather, shaking her head.

Gavan walks down Lakecrest Lane, pointing to Lynskey's work. Four houses in this subdivision were built by Lynskey, the amenity buildings too from the boathouse to the mailboxes.

His mark is everywhere.

Wouldn't it be nice if it were called Lynskey Lane, he muses?

In his mind, it always will be.

The evolution of Matheo Dürfeld

Matheo Dürfeld hasn't built a log home in five years. Don't be fooled by that; business is... busy.

But as times have changed, so too has he — evolving to meet those changes.

For a man, whose company in many ways symbolizes the so-called "Whistler-style," his latest project is a massive departure from the norm.

Instead of heavy log and timber, there's exposed concrete, glass flown in from Italy, zinc roofs, blackened steel and VG fir in a house that takes Whistler building to a whole new level.

And yes, it's true: there's an infinity pool that is cantilevered out of the side of a mountain. To the layperson, that means the pool is supported at only one end — the other end stretches out into the sky. That's 30,000 gallons of water practically suspended mid-air. It's stored and recycled in a cistern, which is cut into the cliff to be kept out of view.

And yes, there are audacious view decks, made from Stanley Park wood, again cantilevered out of the house — heading out to the clouds.

Rising up out of the snowy ground are two large concrete oculi — rounded telescope-like features. They are, in effect, futuristic skylights, one to pour light into the wine cellar below, the other to light up the hot tub.

The windowed corner of the master bedroom looks out over massive treetops, giving the illusion that you too are in a glass cocoon, living above the forest.

There is an over-riding sense of peace from simply looking outside. It belies the level of activity going on throughout the house as the crews work to get it finished.

This project takes contemporary lines to the extreme, where architectural elements throughout the house either line up, radiate or converge on several planes and in numerous materials.

"It's a whole new generation of what building can be," says Dürfeld simply.

It's designed by American architectural firm Bohlin Cywinski Jackson, of Bill Gates and Apple store fame among its many accolades.

"Whether that's even my favourite is not even the answer. It's more... has it been the most challenging?"

Without a doubt. But he's up to it. Or rather, he adds modestly, he has a crew that has embraced the challenge.

Dürfeld has always been in construction it seems. It was, he says, his ticket through university where he studied psychology and general arts and, he liked it more than working in the sawmills of Williams Lake, where he grew up.

He ended up in Whistler in 1978, not to ski, but for a job.

"I got into log building fairly soon on," he recalls from his home office out of his garage in Whistler Cay. "There was a resurgence of log building in the early 70s/mid-70s in B.C."

Everyone wanted to have a log cabin, it seemed.

And so the story goes that one job literally led to another. His small crew became the log building experts — their work showcased around the valley from the Crystal Hut on Blackcomb Mountain to the Four Seasons.

Dürfeld knew that to keep his crew busy he needed to diversify. Log building soon morphed into general contracting where they would oversee a project from start to completion.

He never ventured into the design aspect. Where other guys in Whistler billed themselves as 'design/build' Dürfeld stuck to focusing on the build part, leaving the design to the architects and designers.

"At best we would be then really good at interpreting what they want," he says, with the philosophy of "measuring well and building well."

But his boldest diversification, biggest leap of faith, is just on the horizon.

Three years ago Dürfeld oversaw the construction of the Austria Passive House in Whistler for the 2010 Olympic Games. It was to showcase passive house construction from Europe.

It opened his eyes to the future.

He tested out his theory on a duplex lot in Rainbow and it convinced him that the technology worked, that it could be affordable, that his company could do it, and perhaps most importantly of all, that this was truly the way of the future.

"We believe that this is the next generation of how we should be building houses in North America," says Dürfeld.

The Rainbow Passive House is the first residential building in Canada to be certified by the Passive House Institute in Darmstadt, Germany, it was announced on Jan. 29.

And while North America doesn't have the same kinds of pressures that pushed Europe into passive building such as no secured oil supply, huge energy subsidies, among other things, Dürfeld believes the construction speaks for itself.

"The main reason (to build passive homes here) has to be: they're simply healthier, more comfortable houses to live in."

This year he hopes to begin construction on a plant in Pemberton at the industrial park that will build passive house components.

Does he see it supplying homes across Canada?

"Oh, we hardly have those kinds of ambitions. We'll stick within our own skin... We see ourselves working throughout B.C."

And so his evolution continues.

Dürfeld is nervous. He's excited. This is the biggest investment the company has ever made.

"We're recognizing that we can't just wait for one big house after another to fall in our lap."

The tradition of Andy Munster

Perched atop Andy Munster's large wooden desk in his home office at Tapley's Farm is a small, framed photograph with neat cursive pencil underneath saying "Andy's First House."

It dates back to when he was a boy, growing up in Quebec's Eastern Townships, a mini rudimentary A-frame of sorts, two sides leaning together in a peak, tall enough for a child to scramble through.

You can almost hear the childhood secrets whispered under those two leaning walls, the adventures plotted, plans hatched. A place to escape the world, find respite from the summer sun.

Large trees surround the fort, sunlight glances off a lake in the background.

"My mother sent it to me," says Munster with a slow smile, memories flitting across his face.

On the other side of his desk a golden Georgie award glints in the winter sun pouring through the office window, an enduring reminder of another house Andy built, one who's name — Akasha — came to symbolize just how far the building industry in Whistler had come at the time.

Perhaps it's fair to say that Andy was always going to be a builder; he just didn't know it when he moved to Whistler in 1971 to ski.

To keep skiing, however, he needed to work. And it didn't get any better than a job with the winters off.

"I started right from the bottom, packing lumber, wheel-barrowing cement around — there was no pump trucks at that time — so basically starting right at the very bottom and gradually working up to carpenter's helper, carpenters' supervisor and then project manager."

Within five years he had his own company doing renovations and small houses.

It was around that time he built one of Whistler's iconic homes.

No, not Akasha. Not yet. But, by and by, this house would come to have its own name too.

"We didn't really have a name for it," says Andy, harkening back to the carefree hippie days of the mid-70s. "People have called it Munsterville."

Looking at the black and white photo at the museum, B.C. hippies caught in a carefree moment, Andy among them, it's easy to imagine the shenanigans at Munsterville.

If "Andy's First House" was built for fun, "Munsterville" was built out of necessity.

With rental housing scarce back in the day — a problem that would continue to plague Whistler over 40 years until just recently — Munster took matters into his own hands.

He picked a prime location next to Fitzsimmons Creek, close to what are now the present-day day skier parking lots, and built a squat there, complete with a front porch and French windows.

It cost $50.

There were about 30 squatters in the valley at the time.

Munster recalls that as he was squatting, and effectively living rent free, tax free, and mortgage free, he was building an addition onto municipal hall for the land company that was developing the village.

"We would just walk across to work from the squat," he says.

His blue eyes twinkle, thinking about the fact that a new multi-million dollar art museum — the Audain Art Museum — will now call that squatter's paradise home.

He was there until 1979.

Munster couldn't squat forever and as he got married, had a family; one new house began to lead to another. Basic ski cabins in neighbourhoods like Alpine and Emerald morphed into more complicated homes in tonier subdivisions. Munster began designing the homes himself, with the help of his wife Bonnie and local engineer David McColm.

And then came Akasha.

Built not for fun, not for necessity but on spec, gambling on the fact that Whistler's real estate was on the rise, that it would tolerate multi-million buyers.

The gamble paid off.

One month before it was finished, it sold for $7.9 million — the most expensive house sold in Canada in 2000. Munster won two coveted Georgie awards for it.

Thirteen years later, Akasha is still owned by the American businessman who first fell in love with it and had to have it.

It has been up for sale of late and it remains to be seen if someone else will own it soon. But it will always be Munster's.

"You build it, you sell it. But it still feels like yours," he says.

You think it would be his favourite, he muses, but it's hard say which one is closest to his heart. He picks he latest build on Blueberry.

In a changing style that's bringing more modern contemporary looks to town, this build is classic Whistler and by extension classic Munster. Like Akasha, Munster, Bonnie and McColm designed this one from start to finish.

Big round beams rise up through the foundation.

The floor to ceiling windows pull you through, towards the views that are impossible to look away from — Mount Currie and Wedge Mountain from the family room, the golf course and village and Whistler Blackcomb from the dining room, the peak of Whistler Mountain from the living room.

When you think of the Whistler chalet of your dreams, this is what you picture. This is the kind of house where you imagine kicking off your ski boots, snuggling into the oversize couch and watching the alpen glow unfold.

"The house has to feel good when you walk in," Munster explains.

As he walks through that house, he highlights things that make it "his" such as the signature roof downstairs in the games area — Alaska yellow cedar with red cedar trim.

This house wrapped up two years ago and he's been working on a few smaller jobs since then. He's got his fingers crossed that his newest design for a private spa will get approved on an estate lot.

He estimates he's had a hand in about 35 homes in the valley.

It may be a long way from Munsterville, even longer from "Andy's First House," but the old hippie still remains.

Coming to Whistler was "the best move I've ever made in my life."

That's not because he became an award-winning builder/designer, not because he was able to make a living from these multi-million dollar homes.

It was the fresh air, the mountains, the lifestyle: "That, to me, is worth millions."