It's enough to turn everyone into a vegan.

Last week, reports of possible metal shavings in meat sparked the recall of meat products packaged in Port McNeill, B.C. The recall involved beef and pork products and was initiated by a Vancouver Island store.

Metal shavings in meat is like reporting sawdust in a brewery. Or critters in the cake flour of a bakery. Time to take stock.

It takes roughly five to 20 kilograms of feed and about 15,000 litres of water for a kilogram of beef to be produced, whereas it takes only two kilograms of feed and less than one-third the water to produce a kilogram of chicken. And within 35 years, we could run out of the land needed to produce the beef that fuels the carnivores.

Consider the Guinness-worthy temptations: You can walk into steak houses and order 20-ounce steaks. That's enough to feed four or five people. For a solitary diner, that's just greedy. Or perhaps Wagyu beef, for which a small steak costs about $90. That's just wrong, but it seems to be in our nature to go big, go expensive, go for a coronary.

And it's killing us.

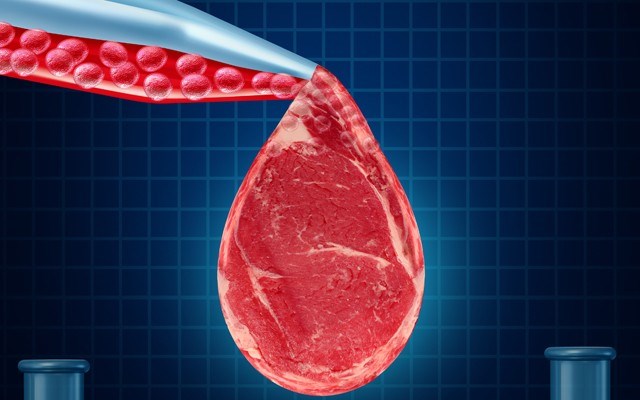

A recent story in the Financial Post cites research and development that is underway in the grossly unappealing sector of making fake beef, or lab beef — also known by the catchy name, cultured beef — in which plants are used to create meat, similar to what a cow eats to produce its flesh and muscle. This is what the future holds as the consumption of beef continues to rise and we wrestle with land use.

So consider the options: worms, and crickets — and any number of insects and critters — that can be ground into a powder to boost the protein content of non-meat alternatives.

We may not be ready for that. Or are we?

Twenty or 30 years ago, raw fish wasn't even considered as we pursued our fetish for cow and chicken flesh. Today it is so routine, and largely inexpensive, it is difficult to remember a time when we weren't addicted to that silky-smooth, clean sensation on our tongues along with that hit of wasabi.

And soy milk is so much easier to digest for Western cultures weaned on cow's milk, which led to generations of flatulent, lactose-intolerant sufferers. A few decades ago, we wouldn't have known a soy bean from a navy bean. In the past decade, sales of non-dairy alternatives have charted skyward as nuts, rice and coconut have become the darlings of the milk-alternative movement. There is an entire generation that will roll over in their graves at the thought of calling such liquids "milk." That generation was already weakened by that whole margarine thing and it took decades for us to return to the glory days of butter. Progress has been difficult and fraught with misdirection and mistakes.

As you read this, research is well underway to produce new proteins that mimic those found in the real milk. Yes whey. Call it "vegan" and it may just sell alongside the nut milks. But will it taste real?

We are nothing if not determined in our pursuit of mimicry. Remember faux fat? One such product was Olestra, which was discovered by accident but was further developed to replace those naughty fats like those found in potato chips. In the late '90s, Olestra gave hope to the fat-addicted because we could consume the good stuff guilt-free. We still could have that silken, fatty feel on our tongues. Hooray!

But researchers found that it just wasn't the same. The faux fat didn't fool the brain, which understood that it wasn't getting the calories. The result? The body kicks into starvation mode. It's the same with artificial sweeteners: At the taste of the sweetener, the brain is signaled to expect a caloric windfall, and when those calories aren't delivered, the fat-storage process accelerates to convert calories into fat.

At that point, the long-term effects of Olestra were not known. And then came the disturbing reports of gas, bloating, cramping and — the side effect that killed it right then and there — "anal leakage."

What have we learned?

• We'll try anything.

• The best solutions seem to be the real-food ones, not the molecular recreations.

• It's all fun and games until it all goes to anal leakage.

We'll take an order of ground crickets — to go.