After eight years of road cycling, it's easy to exhaust the list of suitable riding itineraries.

In Europe alone, I have pedalled 83,000 kilometres in 35 different countries. The nations I have yet to tour are not household tourist destinations, and are rarely mentioned, if ever, in cycling guidebooks. But curiosity propelled me to explore some of these hidden gems, and since novelty is my addiction, I eventually found myself riding through five different Balkan countries last spring.

Most of my touring has been solo, but for the past five years, my friend Hisano has often tagged along. Like Sherlock Holmes' Dr. Watson, she is always up for an adventure that will take her away from the daily routine. She knows, however, about my only condition: No supper until we've ridden at least 100 kilometres.

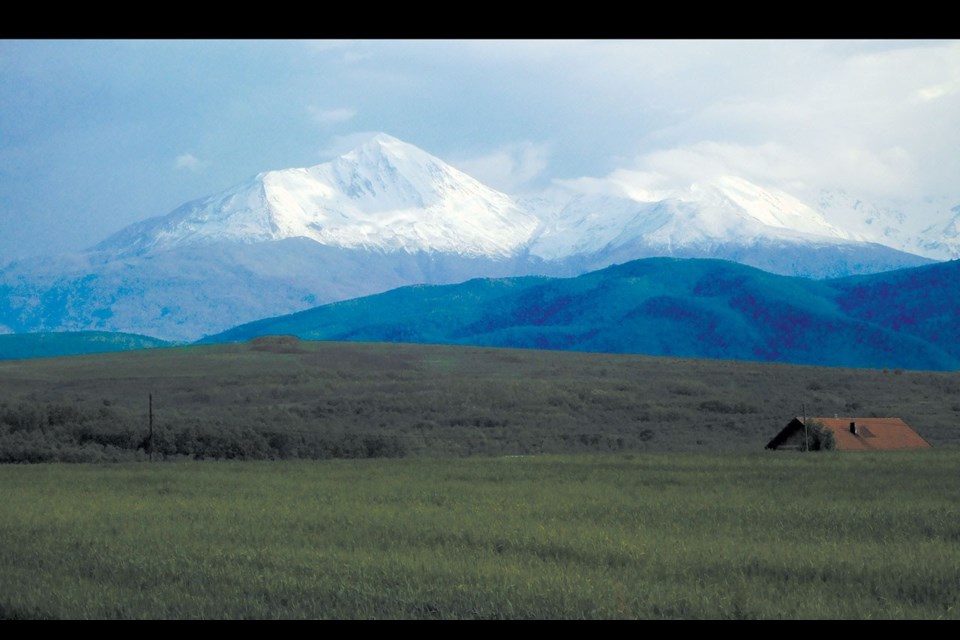

We first fly to Dubrovnik, Croatia on the Dalmatian coast of the Adriatic Sea. After re-assembling our bikes following the flight, we walk the cobblestoned streets of the walled city. Then we click into the pedals and leave conventional tourism behind. We won't even see a McDonald's for the next 950 kilometres as we exit Croatia to ride Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Kosovo, Macedonia and Albania—all new nations I can cross off my cyclist destination wishlist.

If I had bothered to consult any travel literature before departure, I suspect it would have applied the term "rustic charm" to these destinations.

But I found myself pleasantly surprised. All that I seek on a bike tour is quiet, paved roads with a scenic view, and half-decent accommodation. The Balkans consistently delivered these amenities.

As usual, we hadn't booked our rooms ahead of time in order to maximize spontaneity and adventure.

Be aware that hotels and restaurants can be quite smoky in the Balkans. But I've found an effective technique to manage the secondhand smoke without visiting a laundromat—just don your cigarette-smoke-impregnated clothes as your outer layer while biking through a high mountain pass. They will smell perfectly fresh by the time you complete your descent.

Unaccustomed to foreign visitors, the locals are often disarmingly friendly. Along the way, we were offered free wine, coffee and even hardboiled eggs!

In Bosnia, one helpful man guided us behind his car to the town's only hotel. It turns out to be a rather challenging two-kilometre ride, as he's evidently not aware that, unlike motorists, we cyclists don't typically maintain the same speed uphill as down.

In Montenegro, a kind motorist stops and motions for us to load our bikes into his old station wagon as we trudge up the biggest climb of the trip. Hisano expresses interest, but I decline, reluctant to forsake the chance to bike in the five-degree Celsius drizzle!

To our consternation, the local dogs are not nearly as welcoming as the people. We found ourselves constantly threatened by malicious, unchained animals that surely consider us aliens from another planet, with our high-viz Gortex, sunglasses, and the strange plastic things on our heads—nobody wears helmets here. But with my degree in advanced canine psychology, I'm usually able to negotiate safe passage ... or just throw rocks! The latter approach is also practiced by a group of Albanian boys, but their favourite target is not dogs, but foreign cyclists.

Other than too much cigarette smoke and not enough toilet paper (be sure to bring your own), the only real disappointment for me in the Balkans was my failure to add any new bird species to my life list.

After eight days in six countries on the east side of the Adriatic Sea, we board a ferry to Bari, Italy. It's prettier and cleaner here, the food and wine superior, and communication has been fully restored (Italian is my native language), the bathrooms are consistently supplied with toilet paper and smoke is conspicuous by its absence. I'm reminded why tourists with more limited time tend to favour Italy over Kosovo.

The highlight of the second week is the day we intersect the Giro d'Italia, the 100th edition of this country's version of the Tour de France. Italians harbour both individual and collective disdain for unnecessary order and protocol. For example, I long ago discovered that in contrast with the uptight French tour, nobody objects if you ride your bicycle on the Giro's stage route, cleared of all motor traffic a few hours prior to the arrival of the peloton.

Mysteriously, local cyclists rarely exploit this golden opportunity, so we have the road all to ourselves that day. Hisano and I are saluted by thousands of tifosi (local sports fans) lining the car-free highway. Finally, after almost 60 km of fun and glory, we are waved off the road by a carabiniere (policeman) just minutes before the day's race leaders speed past.

Like those pro racers, the time spent in Italy seems to always go by too fast. It's pleasant to indulge in comfort and convenience sometimes, so we'll be back here some day, but in the meantime, curiosity and novelty will continue to fuel my passion.

I've been riding my bicycle in Europe on a regular basis ever since my medical school days in the early 1980's. On my very first tour, six weeks alone in seven countries, I had plenty of time to formulate my personal philosophy without the distraction of a mobile phone or the Internet (in fact to this day, I still travel with no technological support system).

At the age of 21, I concluded that there were only three elements essential to a lifetime of happiness and fulfillment: time, money and passion. I resolved that my future job must provide enough of the first two ingredients in order to regularly indulge the third. But passion No. 1 since childhood has been the engagement of mind and body in the pursuit of knowledge and beauty. This is epitomized by travel by bicycle.

First as a locum (substitute doctor) in rural and remote areas across Canada, and then with a solo practice in the Arctic, and now with a family practice here in Whistler, I've maintained a healthy work-leisure balance, never taking less than 12 weeks off of work per year. In the process, I've presumably averaged less income than many colleagues, but a penny saved is a penny earned. A natural minimalist, I limit my personal material consumption. Rather than pulling a motorboat behind an SUV, I prefer to pull my dirty clothes in a trailer to the laundromat, behind my bicycle.

Now a year after this last European trip, I'm thinking, "Why stop at 40 countries?" I've still got plenty of passion at my disposal, and there remain several obscure European nations that must be explored by bike—birds or no bird, smoke or no smoke, toilet paper or not—and regardless of the number of man-eating dogs that may inhabit them.