When I took my Avalanche Skills Training (AST) Level 2 back in 2016, one of the included pieces of course material was (and I believe still is) Staying Alive in Avalanche Terrain by Bruce Tremper. I learned a lot about avalanches on that four-day course (if you're interested in reading more about my impressions, Google "The Outsider" headlines: "Some lessons learned from the AST 2" and "Debating the direction of continuing avalanche education" on the old Whistler Question website), but I found the accompanying textbook was used more as a reference rather than required reading.

I promised myself I would come back later and read through those 320 pages cover to cover, but like many of tasks on my to-do list, I procrastinated. At the start of each winter, I'd try to re-motivate myself by placing the book on my kitchen table as a reminder. That's never worked, so I tried leaving it on my nightstand in hopes that I'd start reading before bed instead of the latest nerd adventure by Ernest Cline. The thing is, avalanche theory can at times be tedious—and dare I say it—boring. I'd fall asleep before I scarcely made a dent in the first couple of chapters.

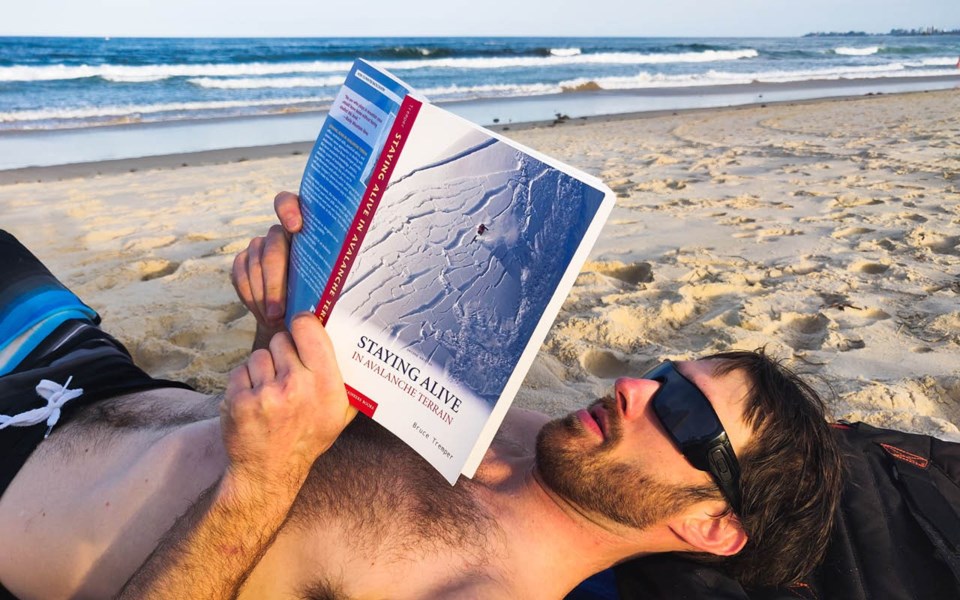

Then my girlfriend and I issued each other a challenge. I was flying home to Australia for a week to see family and had a few dozen hours of long-haul flights and connections on my hands. We made a pact that by the time I returned, we'd have finished (or come close to finishing) this book once and for all. I'm currently halfway through my mini-vacation and am on chapter six of 10 as I write this overlooking the beautiful beaches of Queensland's Gold Coast, so I consider myself on schedule. To motivate you to pick up this book and finally get the holistic avalanche education you deserve to complement your practical experience in the field, here are a few takeaways from Staying Alive in Avalanche Terrain that reinforced information that hadn't been drummed into me from courses or days in the backcountry yet. Note: the following points should not be taken out of context—they need to be considered as part of an holistic assessment of risk when making decisions. This article is no substitute for reading Staying Alive in Avalanche Terrain.

Accurately measuring slope angle

The three sides of the avalanche "triangle" are snowpack, weather and terrain. Snowpack and weather are never under your control (though you must always observe them) but terrain is 100 per cent decided by you and your party, and is therefore the answer to the risk-management equation. We are taught early on that the vast majority of avalanches occur between the slope angles of 33 and 45 degrees with the "sweet spot" occurring at 38 degrees. Most of us think we are pretty good at estimating (or guestimating) slope angle. Few of us actually are, save ski guides and avalanche professionals, but if we want to make an educated decision about skiing a slope in the danger range of 33 to 45 degrees, we need to know how close to 38 degrees the slope actually is and avoid those slopes like the plague. That means picking up an inclinometer and making sure we are using it properly, i.e. measuring average-slope steepness rather than terrain undulations. Inclinometers are not expensive and are integrated into some compasses, which should be another mandatory tool in your backcountry kit.

Wind is everything

The first thing we check on weather reports for skiing is the amount of recent snowfall, but wind can deposit snow 10 times more rapidly than snow falling from the sky. I previously thought that the stronger the wind, the worse the potential for wind slabs, but in actual fact, pretty much all the winds of concern are between 25 to 80 kilometres/hour. Anything over 80 km/hr (in dry conditions) usually means snowflakes are cast into giant plumes and evaporate before hitting the ground. I'm getting into the habit of monitoring wind speed, direction and duration as part of my daily weather-watch routine. When I'm in the backcountry, I also keep a constant eye on ridgetops to infer which direction the wind has been blowing and where the leeward wind slabs are likely to form. I've learned that ridge wind is rarely the same as wind in mountain valleys, which can come into play when skiing at or below treeline.

Managing consequence

We try our best to assess whether or not a slope will slide, but we should be equally concerned about what happens after it slides, potentially with ourselves or one of our friends. Terrain traps are introduced early in the AST 1, but are we actually assessing every consequence before dropping in to that sweet line we scoped earlier? The more obvious consequences are cliffs and gullies. Some of the less obvious ones are abrupt transitions to flat (can bury a victim much deeper), trees in the avalanche run-out zone (can cause fatal trauma) or a not-always-visible crevasse in the avalanche track (both of the above consequences). Islands of safety are your friends. A possible escape route should always be on your radar in case of a slide.

Tremper has written an excellent resource for avalanche safety with this book. It perfectly bridges the knowledge gaps both before and after people decide to take their AST 2 course. But it won't do you any good gathering dust on your shelf. Forget the 10-year challenge in 2019. Challenge yourself to read this book—cover to cover—instead. There are three copies at the Whistler Public Library; all were in use as I wrote this.

Vince Shuley is interested in staying alive in avalanche terrain. For questions, comments or suggestions for The Outsider email vince@vinceshuley.com or Instagram @whis_vince.