Opening the National People's Congress in Beijing last Saturday, Prime Minister Li Keqiang set China's growth target for the coming year at 6.5-7 per cent, the lowest in decades. Only two years ago, he said that seven per cent was the lowest acceptable growth rate, but he has had to eat his words. He really isn't in charge of very much any more.

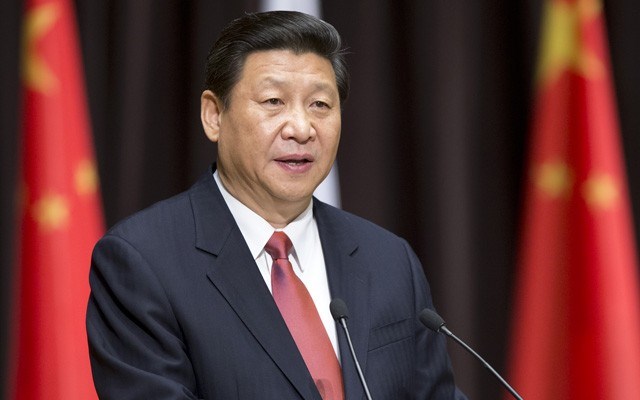

The man who is taking charge of everything, President Xi Jinping, is now turning into the first one-man regime since Deng Xiaoping in the 1980s. The "collective leadership" of recent decades has become a fiction, and Xi's personality cult is being vigorously promoted in the state-controlled media.

Xi has also broken the truce between the two major factions in the Chinese Communist Party, who might be called the "princelings" and the "populists." Xi, as the son of a Communist Party revolutionary hero who ended up as vice-premier, is princeling to the core. His centralizing, authoritarian style is typical of this privileged breed.

The populists, like Li Keqiang, are generally people who grew up poor, usually in the interior, not in the prosperous coastal cities. They rose to prominence more by merit than by their connections, and they are more alert to the needs of vulnerable social groups like farmers, migrant workers and the urban poor. Most of them have come up through the Communist Youth League, and are known in Chinese as tuanpai ("the League faction").

Frightened by the non-violent demonstrations that challenged the Communist Party's monopoly of power in 1989, for almost three decades these two factions have carefully shared power and never attacked each other in public. Xi has now broken that non-aggression pact, authorizing open attacks on the "mentality" of the Communist Youth League in the media.

The friction between the factions has grown so great mainly because the Chinese economy is stumbling towards a crisis. Neither faction has a convincing strategy for avoiding the crisis, but each has come to believe that the other's political style —authoritarian for the princelings, populist for the tuanpai — will make matters worse.

The Communist Party's dictatorship is founded on an unspoken contract with the population: we will provide constantly rising living standards, and in return you will not question our authority. But no economy can grow at 10 per cent a year forever, or even at the currently advertised rate of 6.5-7 per cent.

In fact, China's growth rate actually collapsed about seven years ago, but it has so far been hidden by a binge of debt-fuelled investment. When most of the world went into a deep recession after the financial crisis of 2008, the Chinese regime artificially kept the country's growth rate up by raising the proportion of GDP devoted to investment in infrastructure to an incredible 50 per cent.

In the following five years, China was building a new skyscraper every five days. It built more than 30 new airports, subway systems in 25 cities, the three longest bridges in the world, more than 10,000 km of high-speed railway lines, and 40,000 km of freeways. Tens of thousands of high-rise residential towers went up around every city.

But the new towers remain largely empty, as do many of the freeways.

All of this investment has been counted in the GDP figures, but up to half of it, or maybe even more, is bad debts that will eventually have to be written off. If only half of it is bad debts, then China's GDP growth in the past five years has really been around two per cent, not seven to eight per cent.

The crisis can be disguised for a while longer by printing more money, which the regime is doing. But that is putting downward pressure on China's currency, the yuan, which is currently over-valued by around 15 to 20 per cent. Devaluation would give a temporary boost to China's exports, but it could also trigger an international trade war that would drag everybody's economy down.

So at the moment China is spending $90 billion in foreign exchange each month to keep the value of the yuan up, but even with its immense foreign exchange reserves that is an unsustainable long-term policy. Sooner or later there is going to be a "hard landing," and the regime's very survival may be at risk.

There is no evidence that President Xi Jinping has a better strategy for mastering this crisis than the rival faction, but the storm is obviously approaching and he is battening down the hatches.

In his view, that means taking absolute power and building a personality cult of a sort that has not been seen in China since the demise of Mao Tse-tung. He is certainly not a vicious megalomaniac like Mao, but he clearly believes that he will need total control to get through the storm without a shipwreck.

Gwynne Dyer is an independent journalist whose articles are published in 45 countries.