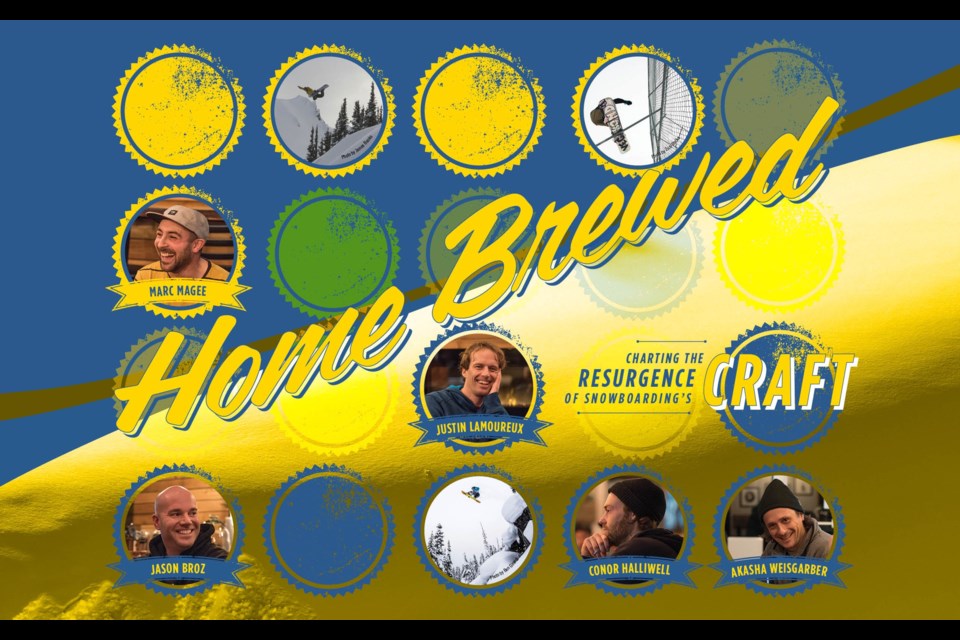

The snowboard industry is a grind, a determined walk through uncertainty. Little is guaranteed, returns reflect passion, and work/life balance becomes one-to-one. Commitment requires dedication, which in many cases grows unchecked from the sport's inherent joy. But joy alone does not typify the movers and shakers of snowboarding. Change comes with defiance, channelled against passivity, stagnation, and thoughts of life after snowboarding. This past December, four craft snowboard builders met in Function Junction, at the newly minted Coast Mountain Brewery. Each had worked a full day, not one had an empty inbox. And in a way, they were still on duty. But for Marc Magee, Justin Lamoureux, Akasha Weisgarber, and Jason Broz, work is never a total drag. The night's to-do list started with a pint.

I had invited them to participate in a discussion about craft boards, hosted by SBC Business Magazine. Biz, as I affectionately call it, is part of the SBC Media portfolio, a sister publication to Snowboard Canada, SBC Skier, SBC Surf, and a number of other action sports titles. Biz is concerned with the goings-on of the action sports industry. Along with reinforcing audience lifestyle, its mandate is reporting news, trends, and insights of use to snowboard marketers, shop staff, sales reps, and so on. Biz is in its comeback year, itself no stranger to the rocky tide facing snowboarding. About 18 months ago it was pulled from bankruptcy, along with its SBC Media counterparts, by an investor in Toronto. It's now part of the CJ Group of Companies, owned by Jay Mandarino and edited by yours truly. Restructuring and buyouts have been commonplace in snowboarding since 2008, when mainstream board manufacturers reeled with the rest of us. There are still mass-produced, highly recognizable snowboard brands whose future is uncertain. But along the periphery of production chains that reach to Africa and hinge on the moods of public markets, snowboarding has recently seen a resurgence of the craft mentality that marked its beginnings.

Snowboarding's early days were loose — directed, not scattered, but loose. I wish I'd been there. Everything I know about the history, what I've gleaned from magazines and documentaries like Let it Ride and Powder and Rails, paints a picture of a bloom of ideas that painted mountains, minds, and workshops with boarding's bright colours. Innovators — there's no clear answer to who invented snowboarding — like Sherman Poppen, Ernie DeLost, Chuck Barfoot, Dimitrije Milovich, Tom Sims, Jake Burton, Pete Saari, Mike Olsen, and Whistler's own Ken Achenbach — took the inspiration they found chasing waves and ramps in mountain passes to ideas for better snowboards. Through the late '70s snowboards were brought under control by fins and steel edges, the proto-sidecuts of such models were refined as the '80s arrived. Development in materials meant shaped plywood and milled, glassed cores as the first snowboard builders followed influence and instinct. Paradigm shifting inspiration came from the obvious (skis, surfboards, skateboards) and from the obscure (DeLost, a pioneer in fiberglass snowboard cores, first worked with glass building a modular skate ramp for Doug Baxendell's skate shop, Off the Wall Skates). Professional snowboarders, naturally stepping to the role of testers, gave their sponsors envelope-pushing feedback. Achenbach needed a kicktail — he and Neil Daffern designed one with Barfoot in '87. Sims had the edge in a notorious rivalry with Burton, thought to have better equipment — entering the '90s, the Craig Kelly designed Burton Air series tipped that balance for the B. Wherever direction came, it was with raw, stubborn energy. These boards aren't strong enough. We can't do enough tricks. We can't ride these fast enough. We can do better.

SOMEWHAT UNLIKELY

Akasha, Marc, Justin, and Jason are not unlike Ernie, Chuck, Dimitrije and Tom. They're not even all that different from Ken (well, maybe that's a stretch). They live in a different world, one saturated by information, technology, and 40 years of snowboard culture, and as they share space with an established industry they have less room to be themselves. But just like the folks who built snowboards and snowboarding through the late '70s and '80s, they contribute to their sport in workshops, pressing the best boards they can, refining and adding personal flair as they work. Their companies (Akasha's Hightide, Marc's Vega, Justin's Spline, and Jason's KNWN) are very small. They're not noticeably disrupting market share, Akasha's not building a mansion up in Pemby. But the craft board movement is interesting in the historical context of the snowboard market. The fact that these companies have the play they do is somewhat unlikely. One small outfit here or there, sure, but four whose owners were close enough to Whistler, and free for a beer? We weren't exhaustive — Divide Snowboards in Terrace couldn't make it, Kindred from the island missed the ferry. Olive, in Calgary, had been in business too long to match our blossoming motif. There are companies that, to my eye, count as "craft" across North America, in Europe, Asia — and a lot of them seem sustainable. A Gentemstick from Japan will fetch over a grand, and aficionados are happy to pay it. The infrastructure of that particular brand has reached brick and mortar retail space in California.

Why unlikely? Well, there was a time when snowboarding was more of a machine, a far less accepting environment for forays. We hit the mainstream in the '90s, our golden age splashing through corporate awareness as dudes like Andy Hetzel thrashed. The surge let us grow, and by the mid-2000s rippable twin-tip snowboards were being pumped out of China and filling mall department stores. To keep prices low and margins high, those specialty shops with sufficient buying power welcomed the practice of "buy-outs," an off-price model that allows steep discounts on past-season gear. "Got leftover boards? I'll give you 60 on the dollar, pass the savings to the customer." Overstock was a commodity — pressing more boards brought down cost for manufacturers, and the extras could reliably be sold to retailers looking to beef up Turkey Sales. Forty-per-cent off for the customer, a good margin for the shop, more sales and lower costs for the brands — gravy. It was a perfect playground for the big dogs, but not a realistic market for niche players like Spline and Vega to crack. Then came 2008.

When the extravagance of snowboarding was slashed from consumer budgets, shops felt the hit. Buys were reined in, and the large brands that had comfortably overproduced put out a generation of boards that were very difficult to sell. That might have been the year you finally copped a Custom X, surprisingly the perfect size and wearing year-and-a-half old shrink-wrap. The effect was a cull of auxiliary operations — it didn't happen all at once, but over time the CPR stopped on brands like Forum, and once-core companies like Option sold to big-box manufacturers. Practice came closer to make-to-order, and frenzied city folk got the hunger back as "not in a nine" crawled a few hours towards open.

It was an exciting time, and though the story has more subtleties than you'll find here, the resulting environment allowed for a change in the status quo. Smaller (still mainstream) brands emerged, leveraging cooperation and injecting the market with new shapes, technology, and personality. The Internet made direct-to-customer a viable option, which was very important in setting the stage for the craft movement. Even if a small company could get into shops, why should they want to? To pay to play with a distributor, so someone else can eventually process an online sale? Of course, there are benefits to shop presence — bricks and mortar is still our recruitment centre, still the entry point for the hardcore boarders of tomorrow. If that kid is drooling over your boards, you're benefitting. But you can get by without it. And whether in a shop or online, today's consumers see options when they buy, rather than a few bright flags. If a Yes, why not a Hightide? If a Lobster, why not a KNWN?

FOLLOW THE PASSION

And so there was a path for Justin, Jason, Akasha and Marc. That they chose to follow it speaks generally to the passion they have in common and specifically to character traits that spurred them to build. Each of them has unique reasons for making snowboards, as the distinct personalities of their brands begins to hint. Their motivations are, to some extent, apparent in their products, and their approaches can be hazily divined in the details of their marketing. That is to say, each of their personal styles bleeds into their brands. In snowboarding, your style is your calling card. If you're not developing your style, with every turn, air, and trick, you miss out on self-expression, the best part of the sport. As our snowboard builders are all accomplished riders, they follow the maxim that style is everything, in every aspect of life — so we see through to them with even cursory looks at their brands. In gathering the guys at Coast Mountain Brewing, I aimed to dive deeper into their individual styles and motivations to better understand the craft board movement.

By the time first pints were poured, the evening was engaging. Conor Halliwell, a Whistler-born ripper and a budding splitboard guide, had the assignment — the Biz feature was his to write. I tagged along as a fly-on-the-wall. Before Conor started with the questions he'd prepared to direct the evening, it was clear that the builders would give him enough to profile their pasts, presents, and plans for the future in the snowboard industry — and with a healthy dose of personality. Against a fitting backdrop — CMB's wood-detail and handsome décor matched the palpable do-it-yourself sensibility in the room — the boys quickly began to share experience, and a dialogue emerged.

"I got my presses off Craigslist," Marc told us as the guys compared setups, "I low-balled the guy and he went for it. He gave me a bunch of materials, too. I used those for my first boards." Akasha chimed in, telling us how he, Gabe Langlois, and Tyeson Carmody (Hightide co-founders) built their two-tonne pneumatic heat press. They got started simply out of the desire to build and ride their own boards. "We definitely didn't have a business plan," Akasha said, laughing. "We weren't planning on starting a snowboard company."

Justin could relate. His career — which has seen him compete at the Olympics, film video parts, and guide clients through B.C.'s vast backcountry — includes a stint working in snowboard design for K2 Snowboarding. "I knew how to build snowboards from my time at K2, and I just wanted to make exactly the boards I'd want to ride — especially splitboards." Justin's trajectory as a snowboard mountaineer has taken him away from the mainstream snowboard market. Travelling through the Coast Mountains and borrowing climbing techniques to access snowboard lines has led him to demand equipment that performs as well on the "ups" as "downs." An engineer, he had some ideas about how he could build such equipment himself. "I didn't build any boards to sell until people started asking me. They saw what I was riding and wanted it, so I started making boards to order."

And with that, Justin captured a driving force in the craft market — consumer desire for alternatives. While mainstream snowboard companies strive to match user-driven trends, and even work with riders to stay ahead of the game, they tend to paint with a wide brush in response to niche demands. And in snowboarding, an untapped niche can be just enough to move boards. For example, though splitboarding remains the fastest growing segment of the backcountry skiing industry, and of the snowboard hardgoods market, Justin and snowboard mountaineers like him don't necessarily see a perfect split in mainstream offerings. And when the majority of boards are designed with an international market in mind, it isn't all that surprising that a shredder from Squamish would be drawn to the designs of somebody who rides the same mountains as they do, deals with the same slippery skin-tracks and the same snowpack in the alpine.

GIVE THEM WHAT WORKS

These ideas were not lost on anyone, or surprising in the least. On the topic of regional influence, Jason told us he's gone so far as to name his boards for the places they were designed to excel — the KNWN Northshore is a powder board shaped specifically with the snowpack of the city's local mountains in mind. He said: "You can't ignore the specifics of your mountains. Most of your customers are local, and you're building for them. Give them something that works for where they are."

As the builders talked shapes, they drew parallels to surfing. The idiosyncrasies of waves have long demanded advanced surfers be sensitive to the minute details of board geometry. The suitability of a board to a wave might fall to a factor as specific as the curvature of its rails (the edges of the board), and it's common for surfers to build quivers around the moods of even a single location. A surfer, Justin drew from his experience in flushing out his perception of the craft-board customer. "I'm constantly buying and selling surfboards. I've got a room full of them — when I see something new and it makes sense to me, I have to try it." There were nods of agreement: their customers are kin to the surfers who look past board walls and hire shapers for custom builds. The snowboard aficionado is not entirely new — our sport has retained participants from its early days, and as those riders find financial freedom in established careers they've collected snowboards, typically focusing on vintage, limited, or powder-specific decks. Folks in that category have been responsive to the craft-board movement, especially as unconventional shapes such as Akasha's Asymetrip, Marc's Bad Nite, or Justin's the What? make waves through social media. But the influence of surf shapers runs deeper, more central to the builders. Their beachside counterparts show them a way of life as they make and ride boards, obsessing over details and honing artisanal skills in pursuit of the perfect ride.

As beers went down and more of the builders' personalities came out, pictures of their brands came further into focus. Akasha, aloof and laid-back, had the same low-key demeanour of Hightide's resin-tinted topsheets of the Creekside shredders you'll see riding boards like the Grease Gun through the trees off Red. Marc's personality was a little louder, in line with his background filming for freestyle-focused companies like Sentury and Grenade, consistent with the raw energy of his team riders (you can see the Vega team in several web series, including Put it in the Bowl and Oil Country). Justin stayed focused on technical details, excited by opportunities to trade notes on materials and building techniques. And Jason's industry background and expertise shone through, as he gave matter-of-fact advice honed by his years heading R&D for Endeavor Snowboards, consulting for companies like G3 and Stepchild, and working with snowboard factories around the world. There was a clear sense of camaraderie and cooperation as Jason shared his opinions of various growth strategies, such as working with distributors and attending industry tradeshows. He both shed light and reinforced strategy ideas the others had come to on their own.

The discussion drew plenty of insight. The builders talked over the difficulty of balancing production and distribution costs with prices, and discussed the possibility of organizing group-buys to collectively save on materials. They debated the virtues of competing tradeshows, stacked pros and cons against the thought of opting out altogether. Conor scribbled away — tradeshows have been of particular interest this season, as new alternatives to longstanding shows have emerged in Canada and the U.S., with The Frog Trade Show in Montreal and Parts & Labor in Denver challenging the status quo. Justin was an outspoken advocate of skipping the headache of navigating that landscape. "If you're doing this to make money," he said, "you're doing it for the wrong reasons."

The sentiment resonated. The truth is that a small snowboard company is not going to knock down a mortgage, and that the work it takes to build a profitable brand is in all likelihood disproportionate to the returns. These guys are still less than five years in — most will have to work other jobs for a while yet. But art is like that, and the drive to contribute to snowboarding comes from the same place of passion that blinds lovers and sets strivers from home. It's compulsive, and though I'm sure each of our builders has faced angst at the end of a bank statement, their work extends the joy found years ago strapping in at the top of some mountain, terrain park, or urban drop-in.

As the evening neared its end, the boys shot the breeze off record. Last pints went down with a sense of ease between us, and plans were made for meeting on the mountain the next day. And though the realities of our workloads meant we'd quickly fall out of touch, soon slip back to the isolation of individual paths, there was a shared feeling that we'd done good work in getting to know each other. Snowboarding has a way of connecting people that persists through lapsed contact — any of you who have struck a friendship on a pow day, or shared laps with a stranger on a shred trip, will relate. Reunions are always happy, and there's never any problem picking up where you left off. So while the defiant drive to continue living snowboarding would soon see the builders alone in their shops, heads down and developing their craft, that evening they'd leave with new ties to the culture that DeLost, Sims, Saari and the others pioneered all those years ago. They'd leave with new ties to snowboarding.

Thank you to Kevin Winter and Coast Mountain Brewing for hosting. Thanks also to Marshal Chupa (marshalcupa.com) and Conor Halliwell for documenting. You can learn more about Hightide, KNWN, Spline, and Vega at hightidemfg.com, knwnmfg.com, splinesnowboards.com, and vegasnowboards.com.