In my trade you get used to it after a while, but the first time you wake up to find a military coup has happened overnight where you live is quite alarming. That was in Turkey back in 1971, when the army seized control of the country after months of political turmoil. It was not as bad as the 1960 coup, when the military authorities tried and hanged the prime minister, but it was bad enough.

There were two more coups in Turkey: in 1980, when half a million were arrested, tens of thousands were tortured, and fifty were executed, and 1997, a "post-modern" coup in which the army simply ordered the prime minister to resign. But there will be no more coups in Turkey: the army has finally been forced to bow to a democratically elected government.

On Sept. 21 a Turkish court sentenced 330 people, almost all military officers, to prison for their involvement in a coup plot in 2003. They included the former heads of the army, navy and air force, who received sentences of twenty years each, and six other generals. Thirty-four other officers were acquitted.

Five years ago, nobody in Turkey could have imagined such a thing. The military was above the law, with the sacred mission (at least in their own minds) of defending the secular state from being undermined by people who mixed religion with politics. Making coups against governments that trespassed on that forbidden ground was just part of their job.

This was the duty that the 330 officers thought they were performing in 2003, according to the indictments against them. The Justice and Development Party (AKP), a moderate Islamic party espousing conservative social values, had come to power after the 2002 election: the voters had got it wrong again, and their mistake had to be corrected.

With public opinion abroad and at home increasingly hostile to military coups, a better pretext was needed than in the old days. So the plot, "Operation Sledgehammer," involved bomb attacks on two major mosques in Istanbul, a Turkish fighter shot down by the Greeks, and an attack on a military museum by Islamic militants. The real attackers, in every case heavily disguised, would actually be the military themselves.

The accused 330 claimed that "Operation Sledgehammer" was all just a scenario for a military exercise, and the documents supporting the accusations (probably leaked by junior officers opposed to a coup) have never been properly attributed. But given the army's track record of four coups in fifty years and its deeply rooted hostility to Islamic parties, the charges were entirely plausible, and in the end the court believed them.

The army has no choice but to accept the court's judgment. The AK party has been re-elected twice with increasing majorities, the party's pious leaders have not tried to shove their values down everybody else's throats, and the economy has flourished.

A new constitution, ratified in a referendum in 2010, has finally made elected civilian governments superior to the army. It even removed the legal immunity that those who carried out the bloody 1980 coup wrote into the previous constitution to protect themselves. As a result, the leaders of that coup, retired generals Kenan Evren and Tahsin Sahinkaya, have also been brought to trial. And about time, too.

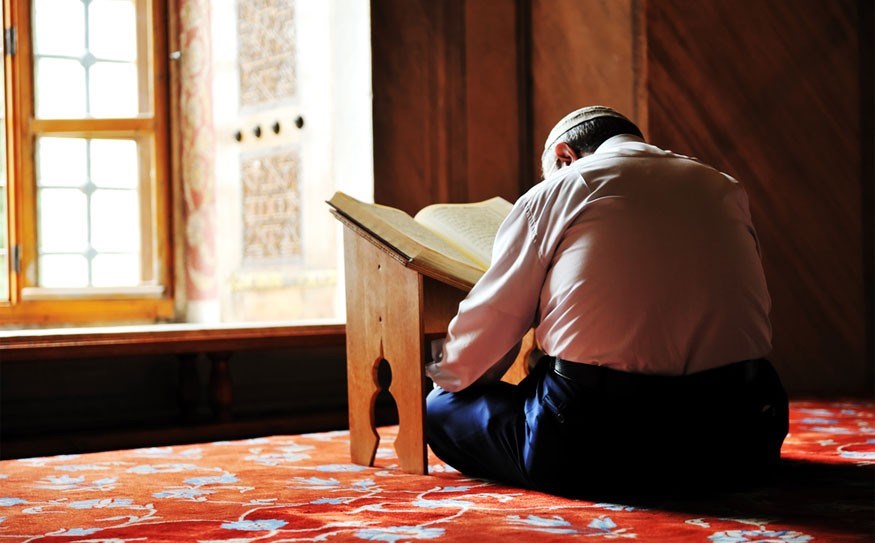

Even now, many secular-minded people in Turkey do not trust the motives of an Islamic party in government. They still think that the army is there to protect them from the dark oppression of the religious fanatics, and that any attempt to curb its power is a conspiracy against the whole principle of the secular, neutral state.

But the Turkish secular state has never been neutral. From the time when Mustafa Kemal Ataturk and his companions, all military officers, rescued Turkey from the wreckage of the Ottoman Empire after the First World War, the state was at war with religion.

Ataturk began by abolishing the religious schools, the Sultanate, and the Caliphate (religious authority over all Muslims) that Ottoman sultans had traditionally claimed. He banned forms of headgear, like the fez and the turban, that had religious connotations. He replaced Islamic law with Western legal codes, and declared the equal status of women and men (including votes for women).

It was understandable, because Ataturk had always argued that Turkey must Westernize its institutions and write off the non-Turkish parts of the empire if it wanted to survive in a world dominated by industrialized Western empires. But that was 75 years ago. Today's Turkey is modern, powerful, and prosperous, and there is no external threat.

It's high time for the Turkish army to stop waging a cold war against the part of the population that are still devoutly religious. They are entitled to the full rights of citizenship too, although they are not entitled to force their beliefs and values on everybody else.

That was the significance of AK's victories in the past three elections, and of the trials that have finally brought the army under control. The head of the Turkish armed forces and all three service chiefs resigned in July in protest against the trials of military personnel, but President Abdullah Gul promptly appointed a new head of the armed forces — who tamely accepted the post. It's over.

Gwynne Dyer is an independent journalist whose articles are published in 45 countries.