It's election season, folks, and the buzz of politics is filling the air louder and more insistently than a bunch of crickets in a prairie meadow on a hot summer afternoon.

Whether it's local elections across the province, B.C.'s important upcoming vote on proportional representation, the stunning right-wing, anti-immigrant upset in Quebec, or the breath-defying mid-terms in an America in moral tatters, seems you can't meander onto a blog or into a bar without stumbling into a conversation on politics and power.

There's an age-old expression: Those who have food have power. But for those of us fortunate enough to live in comfortable, well-fed communities, it can be easy—all too easy—to forget how often and how effectively food gets tied into politics. Food as a political tool. Sometimes a political weapon.

In ancient times, if you were a powerful queen or chieftain, you'd order your enemies' fields burned, their cattle slaughtered, their water supplies poisoned in order to weaken them for the final—hear the zing! of the sword—coup de grâce.

Throughout history, countries have given food aid to friends they supported ideologically and withheld it from those they didn't. During the Cold War, the U.S. spent billions on food aid for its pals while turning a cold shoulder on North Korea, the People's Republic of China, the U.S.S.R.

In 1984, when famine hit Ethiopia, a Christian aid charity accused the U.S. and Britain of blocking food aid to the beleaguered country. They denied the charges, but the motive attributed was believable: They were hoping the strategy would topple the pro-Soviet Marxist dictatorship of Mengistu Haile Mariam. Estimates vary—and how could anyone measure such a horror accurately?—but between 600,000 and 1 million people died.

In a more recent beleaguered country, Venezuela, the Miami Herald and other news outlets have reported that the commingling of food and politics has been taken to a whole new level.

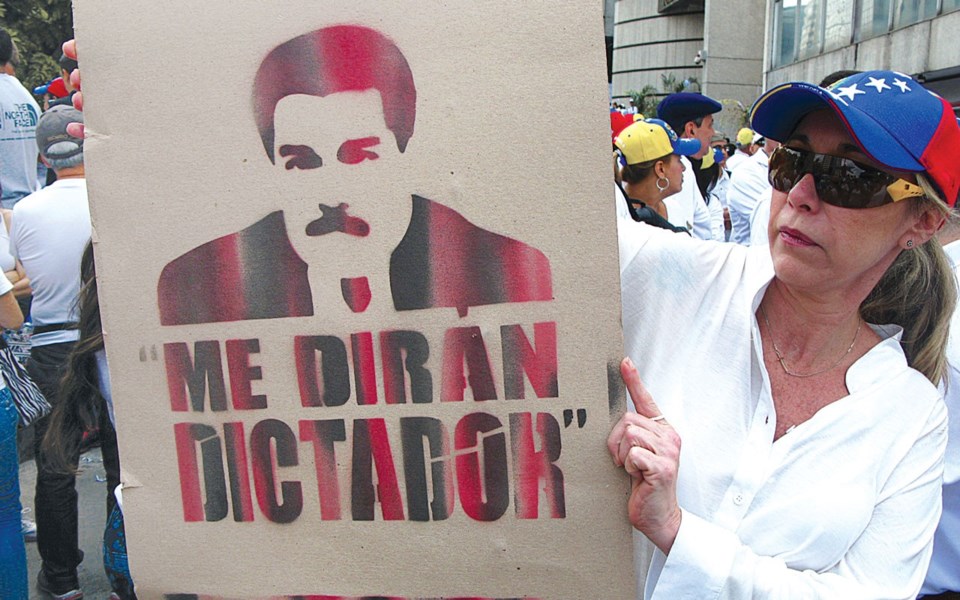

With the country's economy in tatters (estimates are that inflation will reach 13,000 per cent or more this year alone!), rampant food shortages, empty grocery stores, mass exodus and starvation for those who remain are the new normal. So the government under President Nicolás Maduro has been distributing bags of food to counter what it calls an economic war being waged against Venezuela by the U.S. and "other enemies." Nearly three-quarters of the country's population relies on these subsidies.

During the May election, the food/political shamble stooped to a new low. The government issued electronic ID cards called Fatherland Cards as part of its subsidy program. Voters receiving subsidies had to have their cards scanned at a booth next to the polls.

The official line was that there was no direct link between scanning your subsidy card and whether or not you voted, or how you voted, but a lot of citizens were afraid things were otherwise and that by not voting (and not having their Fatherland Card scanned), or by voting for the wrong party, they'd put their food subsidy at risk. Some even refused to vote, food or not.

No surprise. Maduro won.

Then we have the subtler use of food politically to inculcate and cultivate culture. For instance, a number of historians have unpacked the way food was used as a "recipe for democracy" after the Second World War in Canada. An essay of the same title by Franca Iacovetta in Rethinking Canada: The Promise of Women's History describes how, after the war, the traditional source of "preferred migrants"—Britain—was no longer supplying as many newcomers to Canada. More and more migrants were coming from Southern Europe, especially Italy and Portugal, and, later, the Caribbean and East and South Asia.

Iacovetta, a feminist/socialist historian at the University of Toronto and author of a book on post-war Italian immigrants in Toronto, offers a re-reading of that stalwart Canadian icon of the 1950s that so many moms across Canada, including my own, considered their homemaking bible—Chatelaine magazine.

Yes, it was an easy, fun source of recipes and fashion for generations of women, but Iacovetta argues it was also a Trojan horse. "Under the guise of health and welfare concerns regarding well-balanced diets, efficient households, economical meal planning and shopping, 'experts' pathologized the food customs and preferences as well as preparation methods of immigrant women," note the book's editors.

Apparently in Toronto after 1945, Italian women's reluctance to give up their traditional foods and ways of cooking brought them under an uncomfortable scrutiny that triggered various reactions: Some fought Canadian ways of cooking; others learned to create Italian/Canadian hybrids.

That makes me consider my uncle's Italian family and my dad's Polish one in post-war Edmonton. I can only imagine what their parents, all new immigrants to Canada, must have put up with. In the case of my uncle's family, all I know is they were kind, generous people and fabulous cooks, and their family recipe for spaghetti sauce is now our own family's tradition.

When you think about it, whatever country and era migration occurs in, whatever food is brought to the table will reflect much about the personal and public politics of that situation.

As for food and politics in Whistler this election season, I'm still waiting to see if any bars or restos will be predicting the polls by offering a selection of burgers or drinks customers can "vote" on. I guess no one will have to offer an assortment of mayoral burgers or brews, but Jack Crompton could invite us all over to his house to celebrate.

Glenda Bartosh is an award-winning journalist who votes with her grocery items.