The world’s most dangerous places present nothing but

opportunity for Keith Reynolds, a Whistler resident who has just established a

playground in Kabul, Afghanistan.

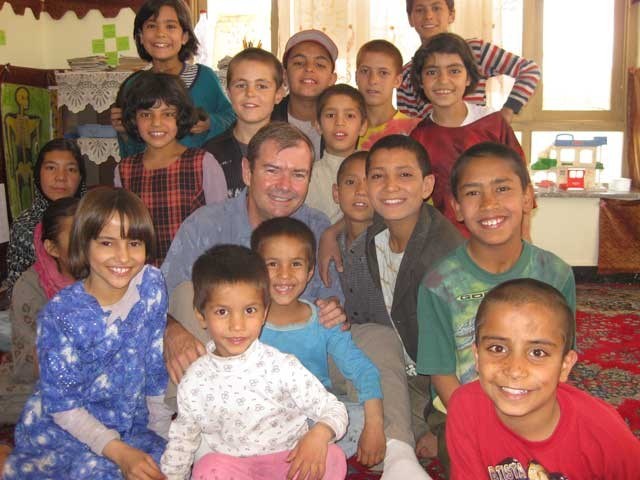

Reynolds, a former forestry worker, is the founder of

Playground Builders, a Whistler-based organization established in 2006 that has

built play areas and gathering places in countries such as Iraq and areas under

control of the Palestinian Authority.

His most recent trip to the Middle East started in May, where

he and two volunteers including Mike Varrin, the general manager of bars for

Whistler-Blackcomb, toured the West Bank before Reynolds went on his own to

Kabul, where he helped touch up a playground at a Kabul orphanage and started a

new one at a girls’ school.

It was an emotional trip for Reynolds, who said in an interview

that Playground Builders is gaining support and making new friends around the

world.

“The best way to make a friend with somebody is to look after

their children,” he said.

The first leg of the trip took Reynolds and his volunteers to

Ramallah, the unofficial capital of the Palestinian Authority. From there, they

went to check out some completed and prospective playground sites throughout

the West Bank.

While the playgrounds were still standing, a number of them had

sustained some damage from aggressive young children, while the more extreme

damage was caused by theft.

“There is definitely some damage that is being repaired now,”

Reynolds said. “The extreme damage was possibly some theft that was taken, some

chain, but most of it is now being covered.”

In order to establish playgrounds in the Middle East, Reynolds

links up with organizations already stationed in the countries where he hopes

to build them.

His partner in the Palestinian Authority is Sharek, an

organization that promotes the development of youth by creating spaces for

young people to engage as “active participants” in all areas of their society.

Their initiatives include cleaning and painting activities in Ramallah and

Hebron.

Sharek covers the cost of maintaining Reynolds’ playgrounds and

helps link Playground Builders up with workers and manufacturers.

Reynolds has also established playgrounds in the volatile Gaza

Strip, which has been marked by sectarian violence between groups loyal to the

Fatah party, which is headed by Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas,

and those loyal to Hamas, a terrorist group that was elected to government in

2006.

Since then, the Canadian government has withdrawn all its

humanitarian aid from the Palestinian Authority, worrying that it could end up

in Hamas’ hands. The embargo on humanitarian aid also means that Reynolds

wasn’t able to check up on his playgrounds in the region.

“It’s too difficult to get into Gaza so we didn’t even try,

it’s basically closed,” he said. “For playground guilders we are currently

working with CIDA on a possible grant through another partner, and they have

been very explicit that there will be nothing to go into Gaza.

“None of our playground equipment will go to anything that has

any association with Hamas.”

Though he wasn’t able to see the playgrounds himself, Reynolds

said he has seen pictures and they seem to be fine.

“They’ve not been bombed by Israelis, they’ve not been taken

apart by sectarian violence,” he said. “By the pictures, they’re fine.”

Once the West Bank leg of the trip was finished, Reynolds went

on his own to Afghanistan, where he encountered two places that touched his

heart.

It wasn’t a smooth trip.

“When I arrived in Kabul at the airport the first person that

greeted me was a man thinking I was from Blackwater,” Reynolds said. Blackwater

is the American private security firm that has been accused of killing

civilians.

The first place he came to was the House of Flowers Orphanage,

where 20 boys and 10 girls had won the “lottery of life” simply by being at

such a good orphanage, according to Reynolds.

“They prepared a room for me, so that I could stay there, no

charge, no accommodation, just to stay with them,” he said. “But when I started

to learn about the stories about the little people that were in there, it was a

little emotional, I found that I couldn't stay there.”

The orphanage was started in 2002 — a hostile time,

according to Reynolds, given that it was the year after the notorious Taliban

were routed from power by a joint operation by the U.S. military and mujahedeen

forces.

The stories of the children at the orphanage brought him to

tears.

“This American couple had gone by and seen these kids,” he

said. “They were crying, huddled up. (They) saw them again, crying and huddled

up. (They) talked to somebody and learned that, yeah, their mother’s gone missing,

so they were just out in the open ruins.”

Another boy saw his father executed in front of him.

“You look at these innocent people and it was just difficult

for me at the time to stay,” he said. “I’ve seen very bad stuff, but when you

put real people to it, it’s very touching.”

Reynolds noticed that the orphanage already had a playground in

place, but it stood on a foundation of dirt and hard rock — a little

dangerous, according to him. Wanting to do something for the orphanage, he sent

an e-mail to the directors of Playground Builders and decided to bring in some

top soil and sod for grass.

“We had to bring in top soil, sod, rough up the grass, remove

all the dangerous debris,” Reynolds said.

The whole thing was done in a single day at a cost of $155.

From there, Reynolds wanted to tour possible sites for a new

playground. That tour brought him to the Tajwar Sultan Girls’ School, a school

with 4,632 students and no playground.

“We know that play is an integral part of growing,” he said.

“There was one broken basketball hoop that is in place. And while I was there,

I witnessed 15 girls trying to play with what appeared to be some kind of a

ball to throw through a broken hoop.”

On the way into Kabul from the airport he had seen a

manufacturer with a slide parked outside in “UN blue.” After some negotiating,

he and the manufacturer, along with representatives from Hewad, the

organization that helped him establish the playground in Afghanistan, came to

an agreement to build five benches, five swing sets, five slides and a soccer

pitch goal. The total cost was $4,540 US, including transportation and

installation.

The next step for Playground Builders is to look into another

project in Baghdad, where Reynolds has already established a playground in the

Northeast section of the city, in one of the poorer neighbourhoods.

For him, a man who has lived and worked in a giant playground like Whistler, play is clearly one of the most important things in life.