In a town where the local economy is dependent on people's discretionary spending, the shape of the global economy is important. What direction the global economy takes in 2013 is anyone's guess. Few are predicting substantial improvement; the chances of it getting substantially worse are good, given the United States' so-called fiscal cliff and the black holes in Europe.

Still, relative economic stability may be a better gamble than seeing NHL games in 2013.

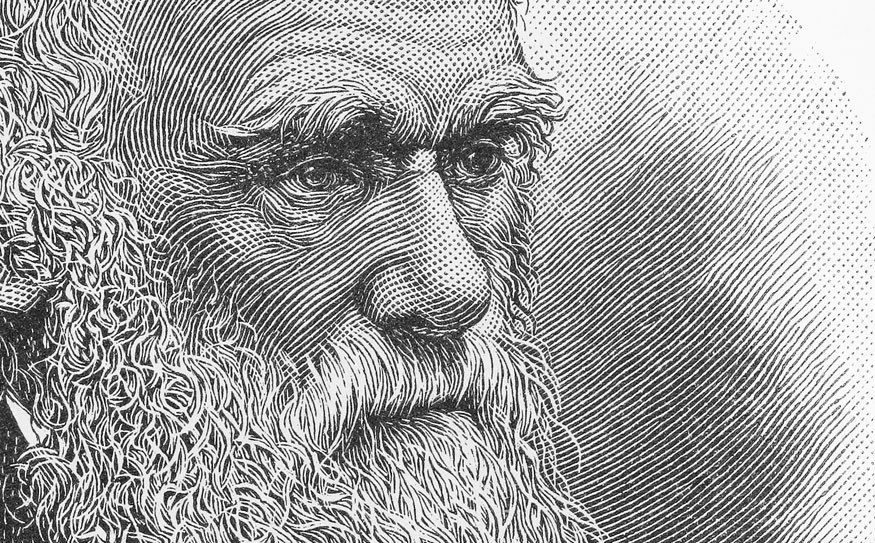

Speaking of sustainability, or the lack thereof, 2013 may be the year to begin a whole new category of Darwin Awards, recognizing our foolishness in continuing unsustainable practices. The Darwins (www.darwinawards.com), for those who don't recall, were created to "honour" those who exemplified the Darwinian principle (simplified as it has become): natural selection deems that some individuals serve as a warning to others. In other words, the stupid don't survive. Last year, for example, there was the drunken man who took off his clothes and entered a bear den at the Belgrade Zoo. The bears, fearing his intentions dishonourable, killed him. He was posthumously awarded a Darwin.

The year 2013 may be the year that collective Darwins are finally awarded, to the NHL, for instance, or to U.S. politicians if they don't avert the fiscal cliff. But as easy and satisfying a target as they may be, we — human beings as a group — have shown ourselves worthy of our own Darwins.

Surely the evidence — the science — is there to conclude that we are changing the climate of the globe. Yet like drunken young men we continue to rip off our clothes and jump naked into the bear pit, an act of defiance and conceit.

Local governments across North America — some of which have been squeezed extremely tightly for dollars — have recognized the threat of climate change. A handful of provincial and state governments have also acknowledged the madness of our ways. Some federal governments in Europe have taken meaningful steps to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. But federal governments in Canada and the United States have done little of significance. And we, the people who elected them, accept this.

At the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in 2010 governments — including the current leaders of Canada and the United States — agree that emissions need to be reduced so that global temperature increases are limited to less than two degrees Celsius. They have ignored that commitment, and we have tolerated their choice of ignorance.

Whistler, with its low altitude, proximity to the Pacific Ocean and dependence on snow, is more aware than most of what a two-degree C change means. In the winter we live on that line, often crossing over and back several times in a week.

Whistler, like many local governments, has made efforts to curb its output of greenhouse gases, despite the lack of effort from senior levels of government. But even with the best efforts and intentions, Whistler is facing a losing proposition. All the "easy" reductions of emissions have been made — the closing of the landfill, the switch from propane to natural gas, etc. The harder decisions are to come. And Whistler's energy consumption continues to rise "as we move toward sustainability."

Back to financial sustainability for a minute.

Among the facts and figures presented to fewer than 20 people who showed up at the first RMOW budget open house was a graph depicting how average daily hotel rates have declined fairly steadily over the last decade. No surprise there. However, other lines on the graph showed how, over the same period, the average daily rate has actually gone up for Americans and Brits. The reason, of course, is the strength the Canadian dollar has gained relative to the U.S. dollar and British pound.

Travel costs have also climbed substantially over the last decade, adding to the price of a vacation in Whistler. While airlines have had their problems and border crossings have become more time consuming, the main factor affecting travel is the price of oil.

In 2003 a barrel of oil was about $26. It climbed to more than $140 a barrel in 2008 before plunging, briefly, back below $40 a barrel in 2009. Since then oil has pin-balled between about $60 and $100 per barrel, roughly three times what it was in 2003.

Our continuing, and growing, dependence on oil — as both a fuel and a foundation of the Canadian economy — is worthy of a Darwin if only because we don't seem to have a Plan B. We seem hell-bent on getting oil out of the ground as fast as we can, with little thought to the cost or consequence.

Oil, of course, is the fuel that gets people to Whistler. Which brings up one of the inherent conflicts in our ultimately unsustainable tourism model: a natural, snowy environment is what we want people to come here and experience, and to do that they have to burn fossil fuels, which warm the planet, to get here.

Is it any wonder the bears fear our intentions are dishonorable?