In the pale predawn light, a time when most of us were trying to wring out the last moments of sleep, with the mountains to the south of me just beginning to take shape, blackened silhouettes against a sky fierce with wind and torn cloud, punctuated by moving lights of late-shift groomers, the muffled sound of a couple of kilos of explosive reverberates down the valley. My windows shake as the percussion plays the house like a giant timpani.

Closer to my bedroom window, a dull rumble grows in loudness and becomes the metallic scraping of an early morning snowplow, clearing a pathway on the street and building a berm of dirty snow at the end of my driveway. More bombs puncture the warm darkness, half-dreams come to a premature end. The hissing and spurting of coffee beginning to drip in the kitchen reaches my ears moments before the smell wakens my nose. Can't remember the last time I used an alarm clock.

In the pale light of the desert's predawn, a few seconds before 6:00 a.m. on July 16, 1945—34 miles (55 kilometres) from where I lived 34 years later—Joe Oppenheimer and his band of mad scientists lit up the New Mexico sky with a 19 kiloton atomic firecracker, the first of its kind on Earth, and turned much of the Jornada del Muerto desert into glass.

For my entire life, the thought that some idiotic politician could bring the 4-million-year human experiment to a fiery end was never far away. As the gene pool plays out and nuclear weapons find their way into the arsenals of countries whose collective wisdom hasn't even reached the Homer Simpson School of Problem Resolution, as the choices for world leader grow ever more discouraging, The Button looms large like a mushroom cloud on the horizon.

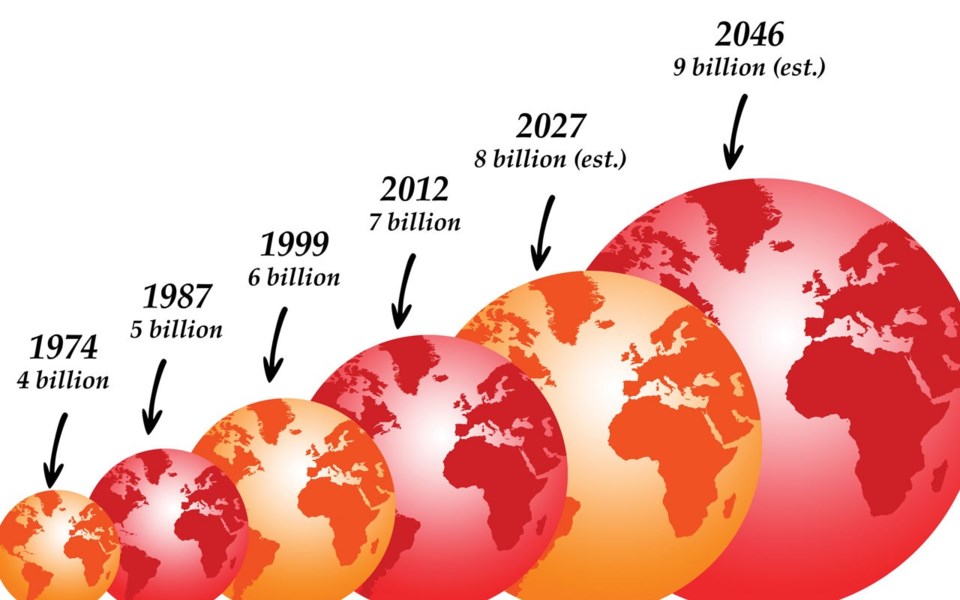

In the pale light of bombs illuminating the deserted, rubble-strewn streets various towns during the Arab Spring, sometime after midnight on Oct. 30, 2011, the 7-billionth human was delivered onto the face of the Earth. What may have been a celebration of life somewhere was cut short by the sound of machine-gun fire and the crying wail of the 7-billionth and first and second and third human born faster than you could say, "Meh."

I love the smell of avalanche bombs in the morning. Well, at least the sound of them. They mean patrol is up the mountain releasing prodigious amounts of snow from places I'll want to be skiing in a couple of hours without having to worry about being buried as the Earth moves under my feet. They're the sound of friendly fire, of peace through power, constructive destruction. They're bombs I welcome and even miss during the ever-growing interlude between ski seasons.

Long before Stanley Kubrick made Doctor Strangelove, I learned to stop worrying and love the Bomb. While other kids grew up learning to duck and cover, I resigned myself to ducking and kissing my ass goodbye. When you live a few kilometres from a Strategic Air Command base, or right down the road from a super secret weapons lab, both of which are first strike targets, hiding under your desk and covering your head is a lot like trying to stop a freight train with a down puffy.

And now, I've finally learned to stop worrying and be happy about the population bomb. More than 200 years ago, Thomas Malthus wrote An Essay on the Principle of Population. The essence of Malthus' argument was that humans are not terribly different than other animals and animals have a natural tendency to breed until they outstrip the carrying capacity of their habitat or predation reduces their numbers. In human terms, he made the mathematical argument that human population grew geometrically—2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64...—while food supply grew arithmetically: 1, 2, 3, 4...

If you think math is hard now, imagine what it must have been like 200 years ago to get your little Dickensian mind around those progressions. Most of the population of the time had trouble figuring out what came after one potato, two potato, three potato, possibly because they had only three potatoes.

It would be unfair to say Malthus' arguments fell into disrepute. They were never considered reputable in the first place. In his time, he was seen as a crackpot by the humanists— who believed mankind was on the cusp of perfection—and as a deranged, dangerous man by the captains of industry who needed more and more people to work in sweatshops making goods to sell to more and more people who could afford to buy them. Not the same people, by the way.

The only guy who thought Malthus wasn't a complete crackpot was a countryman named Charles Darwin. Of course, when Darwin incorporated some of Malthus' ideas into his own observations of natural systems, asking and answering the question who survives when the inevitable clash between population and resources occurs, everyone thought he was a crackpot, too.

When Malthus penned his warning of doom and gloom, the world's population was 27 years from reaching one billion people. A hundred years later, it had doubled. Thirty-two years after that, another billion folks came to the party. Twenty-seven years later, two billion more brought the total to a nice round five billion. Six billion took about 12 years, seven, 12 more. The next billion shouldn't take much over 10. A billion here, a billion there; it starts to add up to real numbers sooner or later.

People still think Malthus was a wacko. Agricultural output has more than kept pace with population. The billion or so people who go to bed hungry every night are victims of the politics of distribution, not production. Western cultures commit parenthood at a rate insufficient to replace themselves. The quarter of a million net new people scratching out an existence on this planet every day are just opportunities waiting to be tapped.

I can't get too worked up about this because I've reached an age where my actuarial odds of outliving clean air, clean water and enough food to keep the inner fire burning are pretty slim. I can coast the rest of the way and leave the worrying to those who are younger while I try to rationalize whatever quantum of guilt I feel about all of this.

So what's this got to do with life in Whistler? Not much...other than that pesky growth thing we keep struggling with. Notionally, we still have a limit to growth here. We still pay homage to our carrying capacity, whatever that is. Few are starving to death; nobody is getting blown up. But growth has been and will always be the elephant in the room. Room's just getting a bit more crowded, eh?