It's ironic that some of the most interesting examples of conservation-minded American architecture are scattered around one of the country's great sprawls.

Phoenix, Arizona - in the Sonora desert, framed by rock-dry mountains and graced with saguaro cactus and other exotic vegetation - is almost 500 square miles of generously sited low-rise buildings. The rest is pretty much roadway and it's next to impossible to get around without a car.

So after rolling off a plane at Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport (the "harbor" should serve as a warning), a shuttle bus delivers you to a rental-car complex capable of holding 5,600 vehicles. Then you and your car will be spit out into a vast region crisscrossed by Interstate Highways, U.S. Highways and State Highways, and with "divided" arterial roads, streets and boulevards of as many as six or eight lanes.

Which is why the very existence of Arcosanti is an anomaly. Because here - in a car-culture heartland - a small metropolis is taking shape (albeit at a turtle pace) in which there is no place for the private automobile.

"The idea is to remove the auto from the city," says Roger Tomalty, an architect and long-time participant in the Arcosanti project. Tomalty and his wife Mary Hoadley, co-ordinator for the Cosanti Foundation, which oversees the project, live in an apartment above the bronze foundry here. But I'm getting ahead of myself.

The Sonora Desert, however raw and potentially inhospitable, is unendingly gorgeous. In Phoenix, the 60-hectare Desert Botanical Garden features hundreds of varieties of cacti and succulents along walking "loops." In the early morning, the sun casts the big saguaro, with its upward-bending "arms," into long shadows. Gambel's quail, with a little black topknot and long-limbed jackrabbits, flit about the natural terrain.

In north Scottsdale, a popular venue - not unlike a perfect miniature mountain with multiple trails - is a naturalist's paradise called Pinnacle Peak Park. Then consider hiking the McDowell Sonoran Preserve in the McDowell Mountains east of Scottsdale.

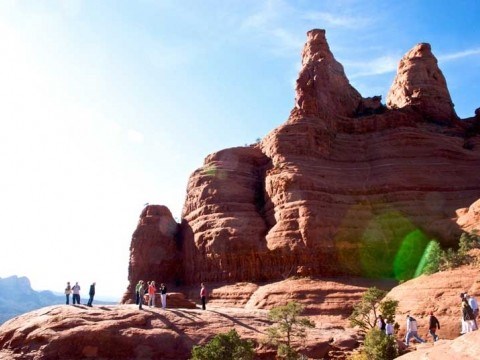

Equally spectacular is the Sedona region, a three-hour drive north of Phoenix, with its Red Rock massifs. For me, a highlight here was a Pink Jeep tour ($75) along the Broken Arrow Trail of the Coconino National Forest. Then, returning from Sedona, I slipped off Interstate 27 near the Cordes Junction, onto a series of unpaved roads on the roughest looking expanse of desert, to Arcosanti.

The Arcosanti story began with architect Frank Lloyd Wright and his winter home and school, Taliesin West, established in Scottsdale in 1937. Among Wright's pupils was Italian-born Paolo Solari who, in 1970, began building this urban environment devoted to sophisticated environmental principles.

Arcosanti (a blend of "architecture" and "ecology") is said to maximize human accessibility, minimize the use of energy, land and raw materials, reduce waste and pollution, and encourage interaction with the natural environment. And while you have to drive to get here, there are no roads within its small urban footprint.

Approaching up a long boardwalk, the first thing you hear and see is a phalanx of Solari's famous wind-bells. These bronze and ceramic creations are sold worldwide to finance the Arcosanti project (originals can cost thousands of dollars).

Erin Jeffries, a resident and spokeswoman, showed me the ultra-modern multi-use community centre, including library and dining room. We walked through the bronze foundry, with its dome-like apses. Here traditional sand-casting techniques are used for construction and bell making. I also saw the emerging solar-driven greenhouse system; the music centre with amphitheatre; and, here and there, a few additional apartments.

"It's a really big idea that will take time," Jeffries says. And while Arcosanti has a legion of supporters, she admits: "There's a lot of dissatisfaction, mostly from those who want it to move ahead."

At present, this would-be city being built mostly by long-stay volunteers (arcosanti.org) looks rudimentary - and the vibe is so laid-back you doubt for its future. With a rueful laugh, Jeffries adds: "The biggest problem, everyone admits, is the United States." Meanwhile Solari, still active at 90, is promoting sustainable urbanism in China.

Back in Scottsdale, I found my way to Cosanti, a sister institution of Arcosanti and the original Solari bronze foundry (once out in the desert). Here most of the Solari bells are made and sold. And here I ran into the gregarious Tomalty, a Greenpeace founder look-alike who attended Habitat, the UN Conference on Human Settlements held in Vancouver in 1976, hobnobbing with the likes of Pierre Trudeau and Margaret Mead.

Still on this architecture-inspired pilgrimage, I made it to the Arizona Biltmore, an historic hotel designed by Wright, as well as to the Valley Ho, another '50s-era luxury hotel inspired by the celebrated architect. Finally I went looking for his Taliesin West.

Here's a fragment of notes scribbled on my laptop that night: "OK to Pima Road, which turns into Princess Road. There's the Pima Freeway in between (not mentioned in instructions), which does go to Frank Lloyd Wright Boulevard. Pull off. Cheap map from car rental makes no mention of whereabouts. Another map shows Pima Road comes to an abrupt end at freeway."

Next time I'll cough up for GPS. Because thanks to my utter inability to deal (calmly) with the roads and traffic, I never made it to the iconic home of modernist architecture.