We drifted down Route 95 through the high desert of southern Utah, awaiting the welcome sign to tell us we'd entered the grounds of the contested national monument. And waited. Ready to get out of the car, we stopped at a site called Butler Wash and took the easy hike across slickrock to view the ruins of cliff dwellings. I struck up a conversation with a ranger who works at neighbouring Natural Bridges National Monument. "So, are we in Bears Ears yet?" I asked him.

"I'm not sure," he said. "I think so."

When even a ranger doesn't know, it's a little unsettling. Welcome to the liminal space of Bears Ears — an area sacred to Native Americans for thousands of years, a national monument for six months. And with so few people that I felt almost lost in time.

The Bears Ears Controversy

Despite the lack of signage, if you drive around the area long enough, you're sure to see the twin mesas shaped like ursine ears. Aha, we must be there.

People have lived around Bears Ears for 3,000 years — first the prehistoric First Nations people known as Basket Makers, later the Navajos, Utes and Mormon settlers. Today, this area is in San Juan County, Utah's poorest and largest. The county is about half Native American, and unemployment rates are double Utah's average.

The many relics of ancient people — shrines, homes, kivas, petroglyphs, pictograms — make Bears Ears culturally, archaeologically and spiritually significant to about 30 Native tribes. Five tribes joined together in 2015 and urged then U.S. President Barack Obama to invoke the 1906 Antiquities Act to designate Bears Ears a national monument. The act allows a president to use executive authority rather than requiring a congressional vote. On Dec. 28, 2016, Obama issued a presidential proclamation establishing 1.35 million acres as Bears Ears National Monument.

Utah lawmakers rallied around extractive industries, and the new President Donald Trump heeded their call. In April, he ordered the Department of the Interior to review all national monuments of more than 100,000 acres designated since 1996. This includes Bears Ears and at least 20 others.

Earlier this month Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke recommended that Bears Ears should be diminished in size. A long legal fight likely looms. And First Nations people are sustaining yet another blow at the hands of the American government.

Are We Bear Yet?

You can understand why my husband, dog and I were eager to see Bears Ears before our view could be marred by a mine or oil well.

But we could have been more prepared. It turned out that the visitor centre in Blanding, the nearest town, was closed on Sundays. I'd wrongly counted on my phone getting a data connection, so I hadn't printed out any info. And expecting a "Welcome to Bears Ears" sign was asking way too much.

Some individual sites have signage, but our best tips came from talking to rangers from Natural Bridges and the Kane Gulch Ranger Station. They pointed us toward some hard-to-find treasures.

Cave Towers

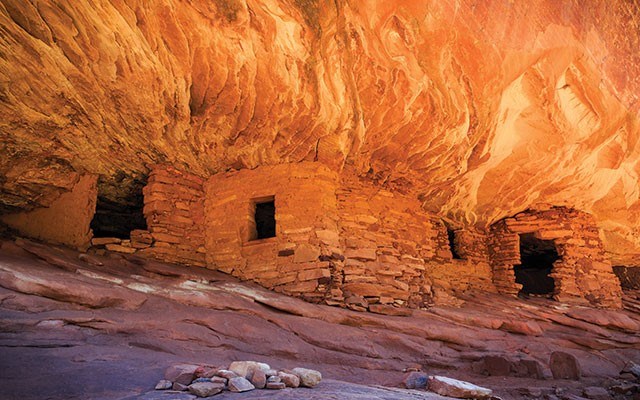

Just past the Mule Canyon site, drive down an unmarked road, open a gate, drive farther, park, walk half a kilometre, and you reach Cave Towers. No wonder we saw no other living creatures but lizards. This late Pueblo ancestral site at the head of a canyon holds the ruins of seven dwellings made of red sandstone brick. On a gorgeous, sunny 11-degree day, we poked around the ruins, which resemble towers, and peered down into the red stone walls of Mule Canyon.

Ballroom Cave

My strongest memory of our day in Bears Ears was sitting just inside the overhang of Ballroom Cave, looking out over a valley of trees and red rock. After a flat trail through the valley, we took a steep side trail up to this cave where ancient people lived, protected in their cave. You can still see the walls they built to partition the rooms, old log ceiling beams, and even petrified ears of corn. This is the best-preserved Native site I've been to that wasn't swarmed by other visitors. We tied up our dog so he wouldn't enter the protected site, and my husband went off to explore.

I'm a creature of the city, and feel more connected to ancestors who were busy developing flush toilets, electricity, computers and other mod cons. But as I sat and looked over the valley, I got just the faintest glimmer of what it might have been like to live up in this cave, making baskets, eating corn and looking out over this same view a thousand years earlier. Quiet, peaceful. Not an oil well in sight.