If you're after the science behind the food on your plate as much as you are the food itself, then check out the latest issue of Scientific American.

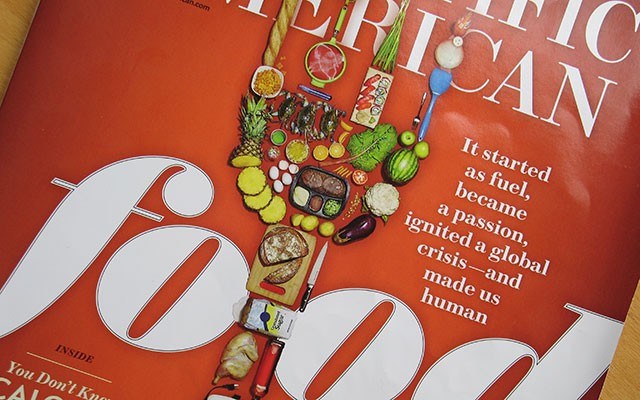

To celebrate this stuff that fascinates, fuels, and sometimes fools us — and, I'm guessing, to also illustrate just how deeply food is embedded into culture — SA has designed three different covers for this special food edition. Each one is dominated by a knife, fork or spoon that's been playfully created out of a vast assortment of food or food-related tools and equipment: a baguette, sliced pineapple, green onions and giant bright blue spatula help make up the business end of the fork while a yellow pear tomato plant in soil, a hot plate with its cord unravelling, and a cutting board laden with cheeses comprise part of the handle.

The three iterations riff on Giuseppe Arcimboldo's much-copied "Four Seasons," the originals of which you can see at The Louvre. Arcimboldo painted this series of four ingenious portraits, all in profile, in the 1500s using everything from gourds to sheaves of wheat to form the faces — interestingly, all men's.

Like the illustrations on the Scientific American covers, none of the foodstuffs is to scale. Still, Arcimboldo has managed to work them into convincing human forms ("Winter" actually feels a bit haunted). A fat ripe peach for the cheek, for instance, and a golden-green cucumber for the nose, a blush of cherries for lips, and an olive green pod of peas for teeth go into making up "Summer." It sounds cheesy but it works, in a surrealistic kind of way.

If we are what we eat and, indeed, we are, then Arcimboldo was saying a lot in an Italian Renaissance kind of way long before Scottish doctor Gillian McKeith usurped the phrase for her popular books and BBC TV show.

But if you want to go beyond imagery and delve into some of the best science about what exactly it is that makes you what you are when it comes to food, then grab the September Scientific American before it's cleared from the newsstands faster than a bus person clears your table when your favourite restaurant has a line-up.

To whet your appetite, here's an assortment of little amuse-bouches culled from this special issue. Use them to impress your friends at your next dinner party, but it's not a bad idea to have the issue at hand to back yourself up in case of a challenge. When it comes to so many everyday things, like food, truth is often stranger than fiction.

It's all a matter of taste

• In recent years, scientists have found taste receptors all over the body. Seriously. That doesn't mean you'll taste a radish if you rub it on your leg, but it does help explain some long-standing mysteries in the food world. For instance, for 50 years scientists had been trying to figure out why eating glucose produces a much sharper release of insulin than injecting the same amount of glucose directly into the bloodstreams. Then they found out that the cells lining the small intestine also contain taste receptors. When these cells detect sugar, they trigger a cascade of hormones that ends with extra insulin being released into the bloodstream.

• Pregnant women, listen up! Our preference for flavours starts before we're born. For instance, if you're pregnant and drink carrot juice, you're more likely to have a child who likes carrots. Likewise, if a baby's mom eats garlic while she's pregnant, that baby will enjoy the flavour of garlic in breast milk. The reason is embedded in evolutionary justification: if mom eats it, it's safe. So guess what you can do about healthy eating choices.

• How many times did your parents urge you to try it! just try it!, when you didn't want to take even a tiny bite of something new you thought you didn't like. If they were smart, and most parents are, they wouldn't give up right away, and with good reason. It takes about nine tries, on average, for a kid to begin to like the taste of a food they aren't familiar with. If you've got kids of your own, now you know how to manage those tomatoes or artichokes...

Safety in numbers

• The other part of the evolutionary justification about food safety is something my husband and I joke about every time we find a container of mystery leftovers in the back of the fridge and we can't for the life of us remember when we made it. And in some cases, it could well be for the life of us. You try it, we say to each other, applying the same principle that drove medieval monarchs to use food tasters: you eat it first, and I'll check in in 20 minutes to see how you're doing. Evolutionary justification — and survival — through safety in numbers.

Why some people can't say no

• So you just can't stop eating chocolate cake even though you're packing on the pounds and know you should stop? Now there's scientific proof that your problem isn't just a matter of willpower. In one of his lab experiments, Paul Kenny, an associate professor at the Scripps Research Institute in Florida, discovered that rats would choose appetizing, high-calorie foods like cheesecake or chocolate over an endless offering of bland food, even when they knew it meant getting a nasty shock. Studies show that overeating "juices up" the reward systems in our brains to the point that, for some people, their brain's system that tells them to stop eating is literally overpowered. Could you pass me another piece of that cake?

• Don't blame processed food for obesity. Humans have been processing foods for ages, starting with roasting meat 1.8 million years ago. Bread is processed food, as is peanut butter, which goes back to the 15th century, when Aztecs were making a paste of ground raw peanuts.

Glenda Bartosh is an award-winning journalist who certainly endorses this Bertrand Russell quote: "Do not feel absolutely certain of anything."