It was the early hours of a stormy February morning this year, after the nightclubs had emptied into the village, when three young men were rushed into the Whistler Health Care Centre (WHCC) with stab wounds over their bodies.

Unusual for Whistler, this was the serious fallout of an after-hours bar fight turned potentially fatal.

Emergency staff were roused from sleep and the small Whistler clinic, which closes every night at 10 p.m., kicked into high gear. One patient was bleeding profusely and rapidly declining.

With helicopters grounded due to weather, there was nothing to do but frantically work to keep one man alive, and tend to the two other stabbing victims who also had significant wounds, as help rushed up from the city.

The team used "autotransfusion" as part of its resuscitation, whereby blood that was bleeding into his chest cavity was drained by inserting a chest tube, collected in a chamber, and then transfused back into his circulation, which helped save his life.

Whistler's healthcare centre has one small trauma room—although an adjacent room can also be used for trauma—measuring 4.5 by four metres, or 18 square metres (less than 200 sq. ft.). This is Whistler's Ground Zero for serious ski and mountain biking injuries, increasingly complex snowmobiling injuries, backcountry accidents and after-hours fights that can go from serious to critical in the blink of an eye.

For the past two years, doctors and other health advocates have been lobbying for a larger trauma room to accommodate the unique nature of the trauma cases that pass through the small centre en route to emergency rooms in the city, and the modern equipment needed to save lives.

There is even a commitment to fundraise for the trauma room in place thanks to the Whistler Health Care Foundation—but so far there has been a lack of action from the local health authority.

"(The trauma room) is used several times a week," says Dr. Bruce Mohr, Vancouver Coastal Health's (VCH) local medical director at the WHCC. "It's really difficult to run a trauma well. It's too crowded in there.

"The problem is: It was built 25 years ago."

That was before the days of bedside ultrasound, portable X-ray and electronic-records machines, all of which take up vital working space. The centre was also built before the days of the Whistler Mountain Bike Park and long before Whistler hosted 3 million visitors annually, many of those pushing their limits in their thirst for adventure, particularly in the summer.

"Typically we see higher acuity in the summer because of the multi-trauma nature of injuries from the bike park," says Matt Kieltyka, public affairs specialist with VCH. "Skiers and snowboarders generally sustain a single injury, while bike-park riders are more likely to come in with multiple injuries—including head injuries, chest traumas, pelvic, limb and organ injuries, etc.—sustained in the same incident."

With the bike park opening this weekend (May 17), the team at the WHCC is bracing for another busy summer coming on the heels of a challenging winter punctuated with deadly and near-death trauma cases in that small, unassuming room.

Whistler's trauma room: 25 years to now

More than 21,000 people pass through Whistler's emergency department every year. There are days when up to 140 patients can come through the doors in varying degrees of need, from mangled bikers to sick infants.

In the last fiscal year, there were 41 resuscitations in the centre and a further 1,069 patients classified as emergency who may have passed through the trauma room.

Dr. Emilie Joos is a trauma surgeon at Vancouver General Hospital (VGH). She is on the tail end of some of the traumas that start on a hot and dusty day in the bike park or a powder-filled day on Whistler's peak, much like the 29-year-old snowboarder with a ruptured aorta who was hovering between life and death when he eventually arrived on her trauma room table in January.

The snowboarder lived despite the massive odds stacked against him—his outcome a result of the intervention by highly trained healthcare providers working in concert with the on-hill doctor to the emergency team in Whistler to the surgical team in Vancouver.

"It doesn't mean that we can't improve," says Joos.

"From our perspective, if you compared (Whistler's trauma room) to a Level 1 trauma room like ours (at Vancouver General Hospital), it's very, very different.

"(Whistler's) is very small and cramped."

She explains that the average trauma room has a lead physician running the case and typically three nurses (one for IVs, another for retrieving medication and then ideally a third nurse to chart). Others may come and go throughout the course of the case: an X-ray technician, for example, or maybe an ECG technician.

In addition, there are all the machines in the room, not the least of which is the EMR, the Electronic Medical Records apparatus. In recent years, the WHCC switched from paper records to electronic records and the machines are big and bulky. They need to be in the room during an active resuscitation because that's how the medical team orders things.

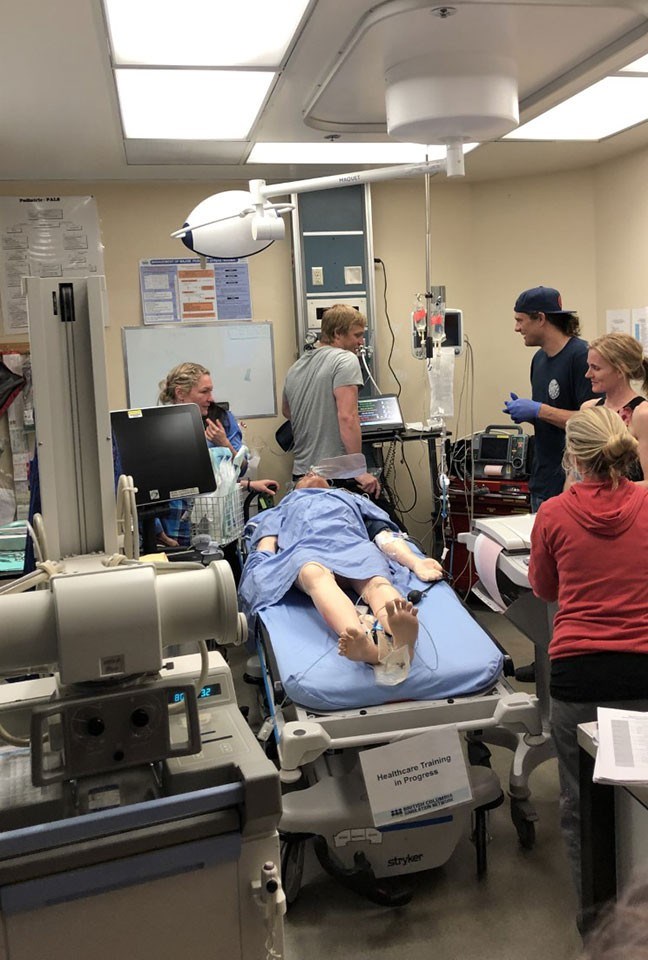

Dr. Shannon Chestnut is a doctor on ski patrol as well as the lead physician for Vancouver Coastal Health's (VCH) Coastal Simulation Program. As such, she's familiar with Whistler's unique trauma cases and how they are treated.

"They see some pretty serious trauma up there," she says.

Chestnut has run simulation programs in Whistler—interactive learning programs using high-tech mannequins to create emergency scenarios that "simulate" reality.

What the Whistler simulations reveal is the lack of space, with staff having to crawl on the floor, navigating chords as they work on patients.

For active resuscitations, notes Chestnut, doctors need space on both sides of the patient's bed. The medical team needs to have proper flow in and out of the room as blood and medical equipment is delivered.

"I know they are a clinic," she adds. "But they function like an emergency (department)."

Lobbying for the future

The fate of Whistler's trauma room rests with VCH, the regional health authority with jurisdiction from Vancouver and Richmond up the Sea to Sky Highway to Whistler and the Sunshine Coast.

While Whistler's small trauma room is on VCH's radar, no decisions have been made on any improvements or possible expansions, such as knocking out a wall to make the room bigger. Whistler, albeit a cash cow for the health authority with its influx of out-of-country patients, is but one small cog in the multimillion-dollar VCH wheel. And while it sees a disproportionate amount of trauma, the WHCC remains classed as a small, rural health centre.

"Vancouver Coastal Health is currently in discussions with staff and physicians at the Whistler Health Care Centre and other partners about the trauma room at the WHCC," writes Kieltyka at VCH in an email. "Because this engagement is still ongoing, we haven't made a final decision on the design or cost of any potential expansion and cannot provide you with specifics at this time. Determining the best option for patient care is the most important consideration for any plan moving forward."

As VCH continues to engage stakeholders, the board of the Whistler Health Care Foundation has made the decision to help—when the time comes. The not-for-profit foundation has played a critical role in the delivery of healthcare in Whistler over the years, successfully fundraising $1 million 25 years ago to help construct the WHCC and its helipad. In the ensuing years, it has come to the table with more—$728,000 for a CT scanner, $160,000 to upgrade the helipad, and $50,000 for the orthopedic operating room at the Squamish Hospital.

Chair of the foundation, Sandra Cameron, says the trauma room issues have been part of board discussions for a while now. The trauma room is clearly a staff priority, and the foundation is listening. Cameron confirms it would support upgrades and a renovation to the trauma room once VCH gives the nod. It will work with stakeholders to establish a fundraising campaign.

"Considering the nature of our population, who are regularly living and playing hard outdoors and have the propensity to push the limits of skiing, snowboarding and mountain biking, it is inevitable that trauma is a disproportionate element of our Health Care Center (sic) cases," she said in a March email. "Therefore the need to continually stay at the forefront of emergency medicine is mandatory. Having a Trauma Room that is fully functional and equipped with the best possible state of the art equipment is the collective goal."

A Disaster Averted

Whistler's February bar fight could have been deadly.

Less than 24 hours after BC Emergency Health Services (BCEHS) rolled out a new initiative to provide emergency blood supply to trauma patients, a team of critical care paramedics was dispatched to Whistler to help those stabbing victims.

The team arrived with fresh blood, straight from the state-of-the-art coolers at their ambulance station, located at the South Terminal of the Vancouver International Airport.

Blood has never been delivered this way before; too many environmental, legal and logistical hurdles to cross. Until this year. Now, new technology means blood can stay in coolers at a consistent temperature for 96 hours, making it possible to be transported up and down the highway with these specialized paramedics via ground or air.

That was lifesaving news for the stabbing victim in Whistler, who was transferred from the healthcare centre into the ambulance and rushed back down to the city.

By the time he arrived at Vancouver General Hospital, he had been given eight units of blood, or about 80 per cent his total blood. Each unit is a 500-millilitre bag and each person has roughly five litres of blood in their body depending on height, weight and muscle mass.

"Trauma patients need a large supply of blood," says Dr. Steve Wheeler, medical director of Critical Care and Aviation Medicine at BCEHS. "If we can keep a patient alive to the trauma centre, it will make a big difference in their outcome and even how long they stay in hospital. This program is going to save many lives."

The patient walked into the Whistler Health Care Centre 10 days after his life-or-death journey down the highway by ambulance to have his staples removed.