Mountains loom large over the Canadian psyche.

About a quarter of our expansive nation is covered by mountainous terrain, and while just 1.3 million Canadians can officially say they live in a mountainous area, roughly 75 per cent of our population resides within 100 kilometres of mountains.

But it’s not just geography that connects us to the mountains. Many of us are linked to the mountains as sources of fresh water and places to recreate and immerse ourselves in nature. As Whistlerites can attest, the mountains also serve a deeper, essentially spiritual purpose, a physical reminder of our relatively brief time on this planet and the greater forces working beyond us.

Canada’s Indigenous mountain dwellers have understood this dynamic for generations, and yet, much of the country’s understanding of our mountain landscapes has relied primarily on the sterile, scientific research of geologists, ecologists, glaciologists and the like.

This can be chalked up, at least in part, to the rigidity of academia, rooted in a colonial mindset that historically favoured disciplinary-dominant research, largely viewing Indigenous forms of knowledge through an anthropological lens, rather than being complimentary to the work scientists were already doing.

“Traditional and Western knowledge systems have important similarities: they both rely on observation, experimentation, pattern recognition, skepticism of second and third-hand sources, creativity and intuition,” writes Olga Lauter, PhD candidate in anthropology at the School of Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences in Paris.

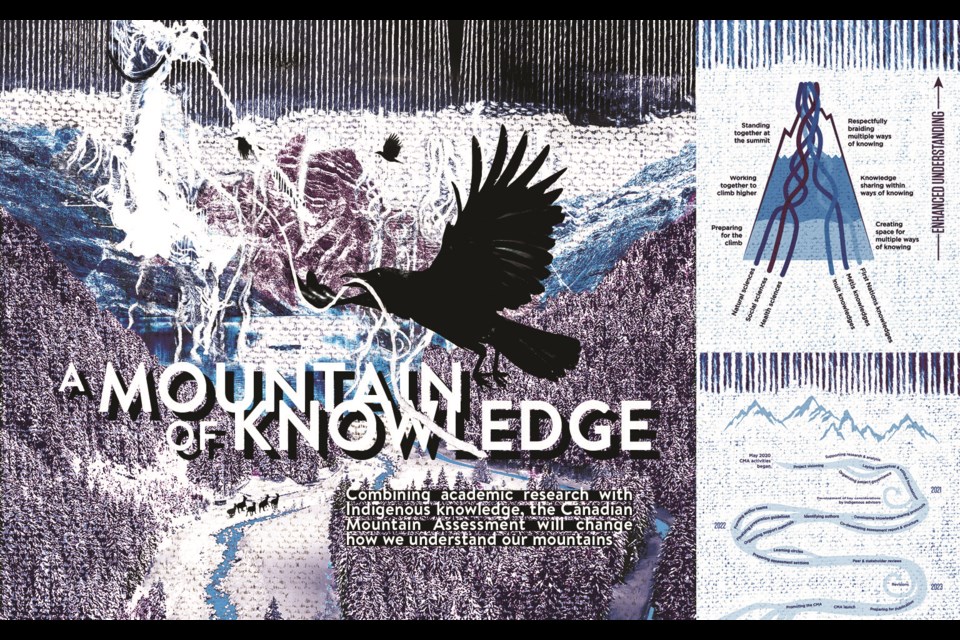

That’s what makes a unique initiative launched in 2020 to advance the understanding of Canadian mountain systems so significant. Based at the University of Calgary and funded by the Canadian Mountain Network and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the Canadian Mountain Assessment (CMA) is a groundbreaking analysis of our mountainous landscapes based on extensive review of pertinent academic literature, combined with insights from First Nations, Métis, and Inuit knowledge of the mountains.

“The CMA is clarifying what we know, do not know, and need to know about Canada’s diverse and rapidly changing mountain systems,” writes Dr. Graham McDowell, project leader and two-time Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change author.

A first for mountain research

McDowell, writing in the Alpine Club of Canada’s 2022 State of the Mountains report, called the distinct approach blending insights from approximately 3,000 peer-reviewed articles with Indigenous knowledge “a first for a mountain-focused assessment.”

“It’s about time,” says Tim Patterson, alpine guide and an Indigenous author of the CMA hailing from the Lower Nicola Indian Band. “It’s taken a while for academia to get to a place that they recognize knowledge is knowledge and how it comes about is not necessarily the most important thing—it’s about actually utilizing it for mutually beneficial ends.”

The CMA’s methodology utilized a multiple-evidence-based approach in which Indigenous and Western knowledge systems are “understood as generating different manifestations of valid and useful knowledge,” McDowell says.

The CMA’s approach treats these respective knowledge systems on their own terms, aiming to “respectfully braid multiple sources of evidence together.” Those sources of evidence will take varying forms, be they text, video recordings of conversations with First Nations, Métis and Inuit knowledge holders, as well as art, photography and maps.

The challenge, according to Patterson, will be to ensure these varying forms of Indigenous knowledge aren’t separated from their most crucial context.

“I think where it could become problematic is if it’s taken out of context because our knowledge is embedded in places and you have to move through that environment to understand what is going on and without that, it’s hard to put that knowledge into practice,” he said.

Guided by a Stewardship Circle made up of a team of Indigenous and non-Indigenous individuals, the CMA’s “spirit, intent, and approach” was co-developed by members, with a total of approximately 60 authors working collaboratively to “illustrate the depth and diversity of mountain-systems knowledge across Canada,” McDowell says.

Expected for release next fall as part of the Banff Centre Mountain Film and Book Festival, the CMA will be a book-length report broken into five main sections: Mountain Environments, Mountains as Homelands, Gifts of the Mountains, Mountains under Pressure, and Desirable Mountain Futures.

Closing the circle

Launched in 2020 and planned as a three-and-a-half-year project, the CMA was of course hampered by the COVID-19 pandemic which, until this spring, meant much of the core team’s activities remained online.

That changed in May when the CMA hosted two important in-person gatherings in Banff: a Learning Circle that included 20 First Nations, Métis and Inuit individuals hailing from mountain areas across Canada, and a meeting that brought 20 of the report’s authors together in a room for the first time.

At the latter, the authors discussed the CMA’s engagement with text and non-text materials; traceability and transparency; and the challenges, opportunities, and limitations of “knowledge co-creation activities” in the context of the final report.

“The gathering helped to solidify mechanisms for operationalizing key ideas and aspirations and generated considerable momentum for the final push of CMA preparation activities,” McDowell writes.

Not discounting the important theoretical work done at the CMA authors’ meeting, May’s Learning Circle showed the true power of the project’s distinct approach. Opening with words from Stoney Nakoda and Blackfoot elders, the group spent several days in conversation about mountain environments, their many gifts, the notion of homelands, as well as the characteristics of “desirable mountain futures” and the many pressures bearing down on our mountain systems.

“Knowledge holders participating in the Learning Circle shared incredibly powerful, illuminating, and specific stories and knowledges about mountains,” McDowell writes.

Patterson was in attendance at the Banff Learning Circle, and said it was fascinating to see the different relationship the diverse group of Indigenous leaders had with the mountains compared to the more academic-minded researchers.

“It’s not that they’re different, it’s that we talk about [mountains] in different ways,” he says. “I think that was the biggest takeaway: academics look at mountains from a distance, and Indigenous people and others like guides and those who live in the mountains are actually living as part of them. Bringing those two views together was important to get a whole picture.”

The sessions were recorded on video as a way to capture and share these orally transmitted stories and are now being woven into the different sections of the CMA (as hyperlinks) under the guidance and review of Learning Circle participants. Notably, these contributions can be removed from the final assessment at any time under the discretion of participants.

At this point, we will have to wait until the report’s release next fall to absorb the information and insights gained from the CMA’s ambitious research, but one thing is clear: it is sure to change not only how we understand Canada’s mountains, but how we study them into the future.

According to the CMA’s own project overview, “This transdisciplinary initiative is catalyzing a community of practice related to mountains in Canada and is expected to set the mountain research agenda for Canada for the coming decade.”

University of British Columbia environment and sustainability professor Lael Parrott, who is also one of the editors of the State of the Mountains report, believes the CMA is a prime example of a wider trend in academia.

“There is a general effort on the part of scientists, especially people working in natural sciences and ecology, for example, to really include and weave in Indigenous knowledge and sciences and putting them on the same level of importance,” she said.

To learn more, visit canadianmountainnetwork.ca.