Doesn’t it sometimes feel like the world is ending?

No matter how religious you are, chances are you have an idea about how our world will come to a finale one day—and that opinion probably relies heavily on the conclusion of the Bible, the Book of Revelation, whether you realize it or not. Written less than 100 years after Jesus’ crucifixion, its apocalyptic prophecy is deep-baked into Western culture and provides the ideological foundation for every artistic depiction of dystopian collapse we see today.

But what if the End Times aren’t a fixed date in the future, waiting to draw all of our human drama and misery to a horn-blowing close, but a series of cyclical events that resilient human beings ultimately survive and learn from? What if the apocalypse has already happened, is happening all around us, and will happen again in the future? How would that change the way you conceptualize your life?

Would it transform how you imagine your future?

THE GREAT FLOOD

Almost every culture on Earth has a story about a devastating flood that covered the entire planet, and the Lil’wat Nation is no different. This is the first great apocalypse of historical memory, a watery cataclysm that nearly wiped human beings off the face of the Earth.

Through the oral storytelling of elders such as Charlie Mack, who passed away in 1990, Lil’wat people learn about how villages near what has become Whistler banded together to load up canoes and survived the rising waters in a pair of flotillas attached to the mountain peaks. This was the story told to Lil’wat artist Levi Nelson, and it ultimately informed both his worldview and his art.

“Every single generation there’s this idea of an apocalypse. On one hand it can be a fear-based thing to control the masses—‘be good because when Jesus returns you won’t go to heaven,’” Nelson tells Pique.

“On the other hand, art can say things that words can’t. I think it’s a natural reaction. Artists are emotional people and in order for us to survive we need to get it out in the form of music or art or writing in order to make sense of what we can’t put into words. It makes it tangible so we can understand and find a way to overcome it.”

Nelson incorporates his cultural learning into his paintings and multimedia creations, which were recently featured at the Invictus Games. He feels a spiritual connection to the land that seeps into the symbology of his work, and his art is an attempt to reclaim the parts of his culture lost or fractured due to colonialism.

“I learned about the great flood as told by Charlie Mack. The great flood is one of our end-time legends that signifies a new beginning. In a sense I agree with how the apocalypse can be cyclical, not just one great ending,” he says.

“It can be identified all over the world in historical crises like the AIDS epidemic and even the world wars.”

IS THIS THE END?

Indigenous artists are increasingly drawn to themes of the apocalypse, world-wide.

For Ojibwe author Waubgeshig Rice, author of Moon of the Crusted Snow and its sequel, the End Times are reimagined as a slightly exaggerated version of the realities facing residents of an Ontario reservation. In Australia there’s The Tribe series, created by Palyku writer Ambelin Kwaymullina, where outcasts struggle to survive in a dystopia overseen by an oppressive government.

In visual art, Blackfoot artist Adrian Stimson depicts stylized buffalo menaced by the iconic atomic mushroom. A quick Google search will yield images of cyberpunk warriors, a derelict version of Edmonton’s Rogers Place, and nude, sunglasses-wearing Indigenous women festooned with futuristic symbols. Deviantart has a surplus of headdress-wearing cyborgs.

Over and over, the future is envisioned as a version of the present.

In 2015, Indigenous writer Rebecca Roanhorse wrote: “What if I told you there had been a zombie apocalypse? What if I told you that you were the zombies?”

LIFE IN DYSTOPIA

It depends on what you count as an apocalypse.

For Indigenous people, the devastating effects of colonialism qualified—their people were decimated, their way of life was irrevocably destroyed, and now they find themselves living in a dystopic version of what once was. Over hundreds of years they witnessed the destruction of their environment, the theft of their homes, and finally the indignity and cruelty of residential schools.

For Nelson growing up, his aunt described their culture as a shattered mirror. With his artwork he’s trying to play with the pieces, and put them back together again.

“Right now white people are talking about the end of the world because they’re being affected by climate change, but the end of the world for Indigenous people already happened,” he says. “First Contact, smallpox, and living on Indigenous reservations—that’s a fucked up concept to me, still.”

There’s a word Nelson embraces: survivance.

“Survivance speaks about the continuation of Indigenous stories, and living Indigenously in a Western world,” he says. “It combines the words ‘survival’ and ‘resistance’ and steers us away from being victims in the system. We’re continuing to thrive with what’s been taken away, and what we still have.”

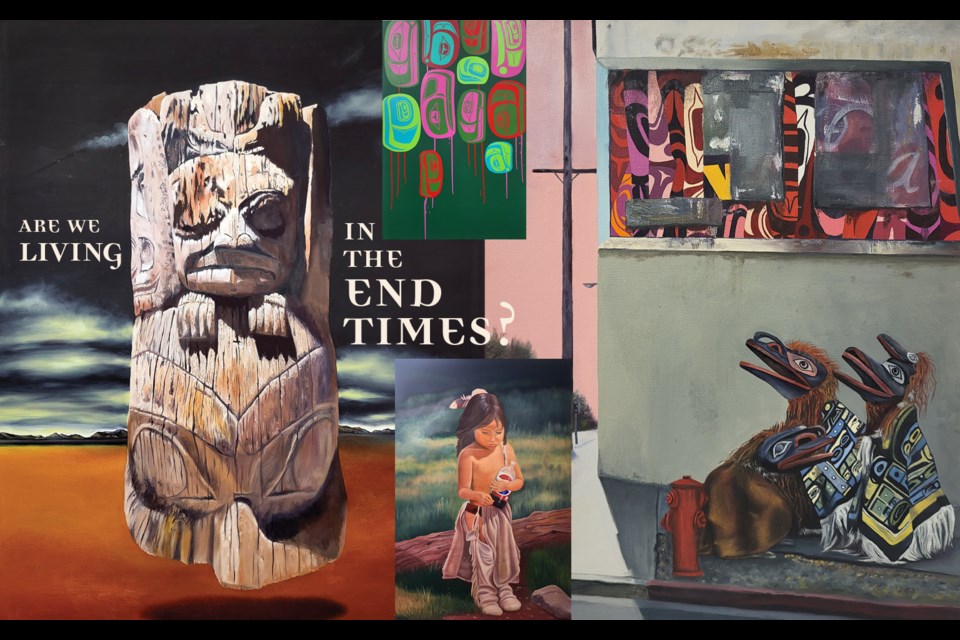

When checking out Nelson’s work on Instagram, viewers see the colliding of different styles in a post-modern mash. One piece can incorporate realism, surrealism and cartoons, such as his piece in which an Indigenous-styled raven trickster sits on a branch amidst a Salvador Dali landscape, a melting clock drooling down beside it like a discarded pizza.

In the foreground, a realistic coyote gazes impassively at the viewer while behind him a Looney Tunes-style silhouette of its cartoon counterpart is creamed against a painting-within-a-painting of a highway.

“When I expand my practice, I’m not limited to baking the same cake over and over again,” Nelson says.

In another piece, he juxtaposes a broken-down rez car with mythology.

“Hamatsa dancers, a thunderbird totem pole and a 1960 Ford Thunderbird create a space where the past and present seemingly collide. I’m thinking about the grandeur of Renaissance paintings, not necessarily in subject matter but in terms of the historia,” he writes on Instagram.

“Although, similarities can be drawn between objects of a sacred nature and their spiritual and/or religious meanings. The broken down Rez car, a common site where I come from, stands as a testament to hope.”

MOURNING

This artwork is born from pain.

Even the most playful piece has its origins at the depths of Indigenous grief, as the artists navigate a world in which missing and murdered women are ignored, systemic racism leads to neglect and death, and Indigenous people disproportionately face everything from poverty to outright violence.

In recent years, Nelson was overcome by the number of funerals he attended.

“I remember being at funerals on our reserve, which last for four days, and at the tail end of 2023 we were losing people left and right. It seemed like every single week, every three days even, somebody was dying,” he says.

“Right at the end of COVID, that seemed like an apocalypse. There was alcoholism and drug overdoses and car accidents. It was a really dark time, and I started keeping a calendar of when people were dying.”

Nelson was moved by the words of a medicine man, emphasizing hope amidst the pain.

“As hard as it is to see, the weak ones are making room for the survivors. He said when a lot of people began to die off, that’s one of the prophecies coming true—because people were being born as well,” he says.

That’s why Nelson doesn’t see his work as being bleak or pessimistic.

“I see this as a period of great change,” he says. “Values are shifting, but people are coming together more than falling apart and I feel like when certain people come along who are corrupt, there’s a reason for that, too. In some ways I see it as a blessing, because it brings about the closing of an era. It inspires people to change for the better.”