To the Nłekepmxc First Nation, everything in nature is interconnected. So it makes sense that this is an overlying theme as nation-member Tim Patterson of Zucmin Guiding leads us on a journey of understanding through the forests of Rogers Pass. As the sun bends its way down through the trees, the warming in open spaces is met by zephyrs of cool air that swirl over lingering snow patches. With airborne phenols from spruce, fir and cedar stirred in, the overall effect is one of marching through a giant, cosmic air freshener.

As an ACMG hiking leader, Master Educator with Leave No Trace, Field Instructor with the Outdoor Council of Canada, MA in Environmental Education, and Indigenous Interpretive Guide specializing in mountain environments, Tim is deeply knowledgeable and has much to share about Indigenous use of various tree species—whether for cleaning, sustenance or other purposes. He quietly passes on his greatest reverence, however, for “the boss tree”—the Interior Douglas-fir used in culinary, medicinal, cultural and technological applications. Not to overlook that these sentinels are also, as always, the most impressive, neck-craning arbour in the forest. Even smaller versions, as here, growing at the erstwhile foot of one of Western Canada’s most iconic glaciers, an ice flow once impressive enough to be called The Great Glacier, a template for geological, human and, eventually, climate stories.

Although several local First Nations tapped the area we’re forging into for resources, they never actually occupied it, Tim explains, sticking to the valleys on either side of the Pass given the difficulty of its steep terrain, dense vegetation, prodigious snows, thundering avalanches and tricky glaciers descending almost to the river valleys. A more recent, European history of the area kicks off with Major A.B. Rogers, a surveyor employed by the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) who discovered this much-sought singular route through the Selkirk Mountains. When the transcontinental railway was completed in 1885, Rogers Pass became one of Western Canada’s first tourist destinations. Glacier National Park was opened in 1886, and Glacier House, a small hotel, sprang up on the rail line near the glacier’s terminus, expanding in both 1892 and 1904. Swiss guides were brought in to lead hotel guests to the ice, which, by 1907, was the most visited glacier in the Americas.

Initially labelled The Great Glacier by Barnum & Bailey-inspired CPR promoters, the Interior Salish word Illecilliwaet (“big water”) was already in use to describe the glacier’s meltwater river, and gradually replaced the former appellation for the ice itself before being officially adopted by Parks Canada in the 1960s. The influx of visitors over the years has included both mountaineers and glaciologists, and thus, though they are sparse by European standards, studies made of the Illecilliwaet Glacier are among the most detailed available for North America. This proved fortuitous given a rapid retreat of the ice that began almost as soon as tourists arrived, pulling it back several kilometres over the course of a century. With the hotel’s raison d’être in slow-motion jeopardy, the CPR’s decision in 1911 to re-route its rail line to make it less vulnerable to avalanches (more than 250 people died during construction and the years following) put a final nail in the attraction’s coffin. Glacier House officially closed in 1925, after which it was deconstructed down to the foundations.

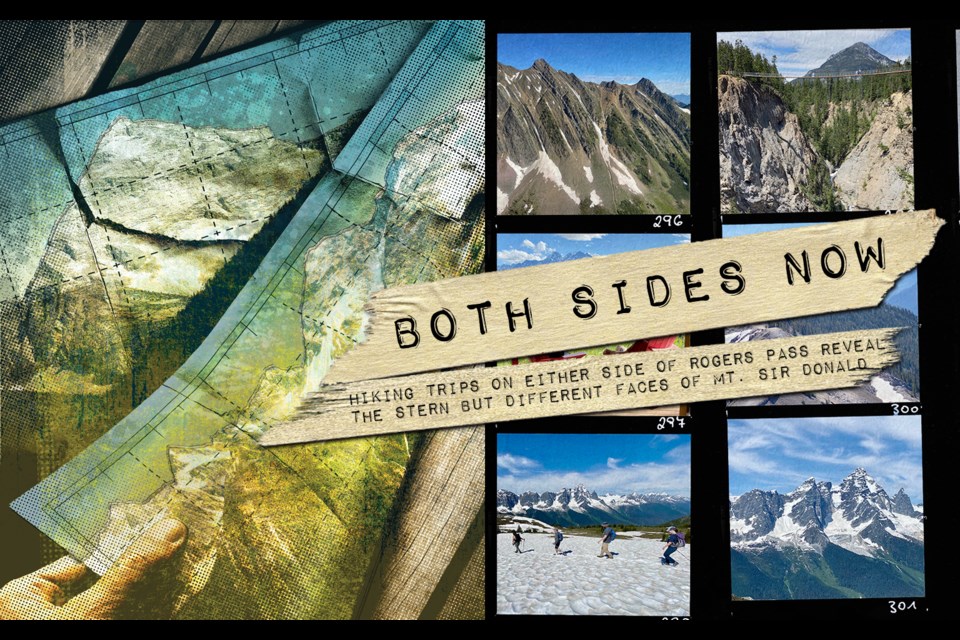

Beginning the hike, we’d walked the abandoned rail bed past the hotel’s historic remains, turning onto a path that guests would stroll after dinner to get a look at the ice. From that same gravel-bar lookout, we now ascend beside the Illecilliwaet River, the thinning forest constellated with house-sized glacial erratics and stranded mounds of rock and till—a Pleistocene souvenir of the glacier’s profound effect on the land. Above us, from every angle it seems, lords 3,284-metre Mount Sir Donald, the sharp, Matterhorn-like peak whose imposing presence in many ways defines Rogers Pass.

Though “Sir Donald” packs a colonial echo, it could have been worse. The mountain was originally named Syndicate Peak in honor of the robber-baron synod that arranged financing for completion of the CPR. Fortunately, sober second thought saw it renamed for Donald Smith, 1st Baron Strathcona and Mount Royal, who led the effort. The peak’s good rock quality and classic shape had already made it popular among alpinists. Since the first ascent in 1890 by Swiss guides Emil Huber and Carl Sulzer, and their porter Harry Cooper, three or four parties a year were tackling Sir Donald by the time Glacier House packed it in. Today, the route up the Northwest Arête is included in the popular book Fifty Classic Climbs of North America.

Eventually leaving the river and forest behind, we labour up a steep, alder-choked slope where the substrate turns to fine dust mixed with gravel—the remains of a towering lateral moraine. If nothing else, the retreating ice has rendered this hike an excellent Glaciology 101. Rock-hopping a small stream flowing off the remaining ice—still high above us and out of sight—we step across glacier-polished rock whose iron content sees it rusting in the air, and lunch where the glacier once sat as recently as my teenage years. In fact, I’d first glimpsed the Illecilliwaet from the window of a van headed west to Whistler from Toronto, and though my memory of an alabaster cascade is all that remains of the ice at this location, I recognize waterfalls and landmarks from old photos included on interpretive panels at the bottom of the trail—a climate-change story writ large.

By conservative estimate, I’d driven through Rogers Pass probably 50 times, but had only ever stopped in one spot—the summit—whether to stretch my legs, use a bathroom, tour Parks Canada’s modest museum, or, when it still existed, log a night at the infamously decrepit mega-A-frame known as Glacier Park Lodge for ski-touring. Seeing the waypoints of the Pass on the ground like this is a whole new ball game, and hiking them to learn how the area’s Indigenous, European, geological and climate histories weave together vastly enriches my perspective.

The ice might be gone, but fascination with the Pass doesn’t change. Later, as our group settles into chairs with cocktail in hand on the deck of Heather Mountain Lodge to watch alpenglow wash Sir Donald and what remains of his once-great glacier, it feels less like a sunset to the day than a coda to an entire era.

Glacier House was an early attempt to bring Euro-style mountain tourism to Canada, with the added bonus, unlike the Alps, of a completely wilderness setting. And it worked. Even as the ghost hotel and the increasingly ghostly glacier it shilled for now pass into the mists of time, interest in the hiking and climbing they inculcated has only increased. You can still access “luxury” lodges in the mountains of Western Canada to have similar experiences, but nowadays you can’t just step off a train; instead, depending on the setting, you drive or fly to them.

In the former category is the aforementioned Heather Mountain Lodge, a cosy, wood-beam structure just off the TransCanada Highway on the east side of Rogers Pass. Fashioned from trees right off the property, it offers relaxed views into the Pass from both the main lodge and a cluster of private cabins, along with a wood-fired hot tub and massive barrel sauna. “Kindle,” the name of the in-house restaurant, is a nod to signature live-fire cooking that features plenty of innovation. My favourite was radish sprouts from an outdoor garden “planted” in a black olive tapenade that had been fire-dried to imitate crumbly soil. Other standouts included a sablefish and melon amuse-bouche, perfectly cooked elk tenderloin atop charcoal-coloured mint-and-pea tortellini, smoked trout, and a flourless chocolate torte.

Though it’s hard to leave behind such culinary delights, more hiking is on our menu, this time in the Purcell Range to the east. To reach our next destination we route through Golden, a town with enough of its own appeal to warrant at least a day and night exploration. You can play it, as we do, like this: take the morning to go up Kicking Horse Mountain Resort to visit its popular resident grizzly bear, Boo, whose 21-year-old head rivals the size of the cub he was rescued as; grab lunch in Canada’s highest restaurant, the lofty Eagle’s Eye, with its signature truffle fries and outstanding views to three mountain ranges and five national parks; in the afternoon check out Golden Skybridge, an adventure concession whose rope courses, climbing wall and canyon-spanning suspension bridges, zip-lines and pendulum-swing deliver requisite gut-clenching.

Making the most of our last night in populous civilization, we stay in town at Basecamp Lodge, a new high-end, self-serve franchise taking hold in the inter-mountain west and dine at the town’s most beloved eatery, 1122, with its eclectic upscale homestyle menu and outdoor tables on the back lawn.

Next morning, we head to the airport for the 15-minute helicopter shuttle into Purcell Mountain Lodge, a wilderness backcountry eco-luxury affair at 2,200 metres in an unbeatable setting—one of the more notable dreamers’ passion projects dotting the subranges of B.C. Another bluebird day brings spectacular views of the local geological nexus—east to the Rockies, Rocky Mountain Trench and Columbia River Valley; west to the Purcells’ Dogtooth Range, Bald Mountain, Purcell Trench and Beaver River Valley, backed by the prominent, looming wall of the Selkirks—a great, silent sea of rock and ice. We’re greeted at the lodge not only by manager Jackie Mah—a mama-bear type who immediately makes everyone feel welcome—but also owner Sunny Sun, a former Edmonton doctor now based in Vancouver. But a backcountry rube when he’d first visited the lodge, Sun was enamoured enough to eventually buy it.

After a quick breakfast orientation, we scramble out with hiking guides and head south to a ridge called Kneegrinder (though it isn’t really), hopscotching around an extensive snowpack that in early July has only recently started to melt, and between whose white corrugations flowers are beginning to bloom. From the ridge we follow a series of high, rolling meadows back north overlooking the deep-cut Purcell Trench and its Selkirk keepers. Though we’re on the complete opposite side of Mount Sir Donald from where we’d hiked in Rogers Pass, the peak is even more impressive.

From this aspect, glaciers galore still sag from the Selkirk ramparts, including the flat-topped Illecilliwaet neve that, without seeing, we’d sat below on the other side of the range. Columbia ground squirrels, a favourite grizzly bear snack, abound, and we encounter many extensive bear digs that document their patient search for these tasty morsels. Since the squirrels eat certain types of alpine plant material that the bears can’t digest, eating the squirrels facilitates a form of energy transfer from alpine ecosystems, whose riches the bears then spread far and wide. With the winter snowpack just pulling back, there’s also a glimpse into the secretive subnivean world that exists beneath it—an exposed ecosystem of roots, snow algae, snow mold, insects and animal tunnels. We break at a jaw-dropping overlook of Mount Sir Donald called Poet’s Corner, then, having filled the senses, climb back up through the forest and out onto the meadow to the lodge.

After a 10-km hike, there’s only one thing on your mind: dinner. Our altitude-activated appetites are amply addressed by Chef Josef, who grew up in Austria’s Alps. His take on contemporary cuisine is influenced by the lodge’s pristine environment with its bounty of wild edible plants and berries. Sated by a round of appetizers and a knock-over dinner (thyme-crusted rack of lamb with creamy polenta and asparagus, anyone?) we look forward to our final day—and last hike.

Next morning finds us tracking across extensive meadows in the opposite direction, through a small watershed divide between the Spillamacheen and Beaver Rivers, then back up the eastern side onto the shoulder of Copperstain Mountain, where we clamber up a still heavily corniced ridge to a lunch spot above treeline. From here, it’ll take us another hour to reach Copperstain’s rocky, wind-scoured summit, but clutching sandwiches, everyone appears silently fixated on another peak entirely. Having moved away from it but gained elevation, we now command a more distant view of Mount Sir Donald’s familiar pyramid—a sentinel B.C. landmark that we’ve happily embraced from both sides now.