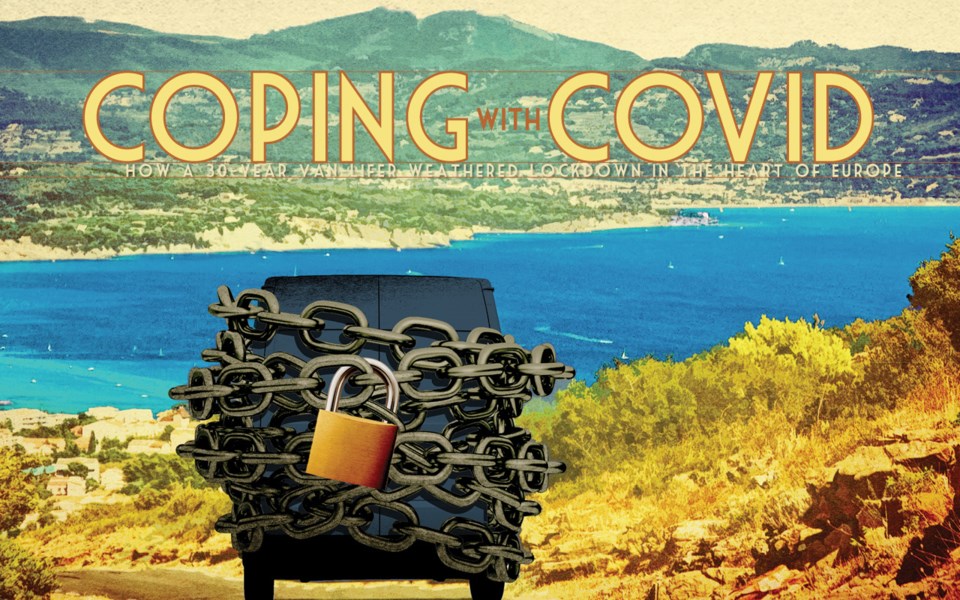

Reflecting on the past nine months and the prospect of what lies ahead resembles a parallel reality. If somebody had shown me a video of life under lockdown when I was 18, I would have thought it a scene from a sci-fi movie. Having lived under lockdown in France for two months and entering a new round this fall, sci-fi has become reality.

Back in the good old days—January, 2020—I left Portugal and three months of riding waves, mountain biking and sea kayaking, to drive to Nice, France, and take my six-year-old daughter on her first ski trip. The Alpes-Maritimes are just behind Nice, where Calypso lives with her Mom, and the perfect place for her to learn to ski. After a fantastic week, she was certified Oursonne (Bear Cub) and we popped in my van—destination: Genoa, Italy—to visit friends.

It was while we were in Genoa that we heard about the first incidents of a strange flu identified as COVID-19 reaching the north of the country. We watched the exponential rise in cases, and I decided to shorten our visit, return to Nice and get Calypso safely home.

As Italian hospitals became overwhelmed and the death toll spiked, people there were taking note. Strangely, people in Nice seemed unconcerned about the situation next door. Public behaviour was cavalier; plenty of bisous, people gathered in close groups, and no masks or distancing.

From a few local cases to national lockdowns in just a couple short weeks, some things changed rapidly. Others, not so much. Despite advice to distance, wear a mask and wash hands, the Nicoise were not buying any of it.

Initially, the French government reduced hours for bars and restaurants, which simply moved people to the streets. The ineffective measure lead to announcement of a national lockdown to start March 21.

As the death count climbed, the fear became palpable.

I bought a van in 2018 to visit Calypso often and escape when the weather turned foul. Most people think living in a van is cool or trendy. The freedom they infer from #vanlife Instragram posts popularized by weekend warriors and vacation vagabonds driving rentals has but a degree of accuracy.

The reality is that unless you park legally, there is a risk of being evicted by authorities or even a fine. Living in a van anywhere near the Cote d’Azur is doubly challenging. The local government does not like camper vans. Public parking areas have height limitations of 1.8 metres, making it impossible for my 2.8-m Ford Transit. I cannot even get into the Nice airport to pick someone up.

When the French government announced a lockdown—or “confinement,” as they called it—I faced a new series of challenges. Playing a game of cat-and-mouse with the authorities and neighbourhood vigilantes for a short period is fine, but lockdown had more serious implications. I needed a safe place to park.

Good fortune arrived when a new friend, Dann, offered a place to park on his property on Mont Chauve, above Nice. I settled in for the long haul, van full of food presciently loaded before leaving Italy, and safely parked on one of the many terraces of this centuries-old farm.

For the next two months, I left the property a grand total of three times. Each time, I had to fill in the requisite Attestation, which allowed for one of five reasons to go out: family, food, hospital, exercise (restricted to one hour) and work (with an official note from your employer). Having foreign plates meant I was unable to drive my van, so I joined Dann on those occasions.

Having travelled solo for almost three decades, I am no stranger to hanging alone, passing time reading, writing, and improving my “camp.”

Calypso’s mom and I decided the best approach was to remain in our bubbles for the time being, but when “deconfinement” was introduced, I drove down the mountain to visit.

The psychological stress I witnessed following the lockdown and the uncertain future ahead convinced me to stay the summer and share as much time as possible with Calypso. We had our own parking spot, now on top of Dann’s land, with views of the mountains to the north and east and an amazing sunrise that beamed through the back doors of the van. Calypso was free to run about, experience nature and be creative without the new worries distancing. We planted a garden.

As summer wore on, we started visiting Calypso’s grandparents and swimming in the pool. And suddenly, summer was over, and she was back in school. Life appeared to being returning to its old ways. For the month of September and into October, I drove down the mountain, walked her to school and enjoyed Wednesdays, when there were no classes, in the park.

But lurking in the background of late August was a steady uptick in COVID cases. Spain, which had been brutally hit by the pandemic, was seeing a rise. Again. Travel corridors were opening and closing faster then travellers could react. In France, the numbers started to creep up, and following the gradual return to school and work, climbed even faster.

By late September, it should have been apparent to national leaders that a serious problem was brewing, but efforts to keep the economy alive precluded strong decisions. Messaging was a complete failure, as evidenced by a series of flip-flops from U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson. Lockdown protests in Madrid, the closing, reopening and closing of travel corridors, the public’s failure to comply with the simple act of wearing a mask, and an unwillingness to accept the science all helped to create the perfect storm.

With October numbers spiralling out of control in Spain, France, Belgium, the Netherlands and even an astonishing rise in Germany, the writing was on the wall, as far as I was concerned. My plan was to spend the upcoming two-week vacances Toussaint with Calypso and head to Portugal.

The best laid plans….

A curfew in France’s hardest-hit cities was extended to the entire nation. But the funny thing is, the virus doesn’t only come out at night and data showed universities and offices recorded the highest incidents of positive cases. The poor decision to continue pretending everything was OK was about to kick Europe in the ass.

It was Tuesday, Oct. 27 when French media announced President Emmanuel Macron would address the nation the following evening. In my gut, I knew another lockdown was imminent. Wednesday morning, I hit the supermarket and filled my van with food and fuel, awaiting Macron’s speech. The question was what day would he choose to lock down given the entire country was in the final days of a major vacation. Thursday at midnight was announced as the start of another lockdown, giving me a 15-hour window to choose to stay or move on.

On Thursday morning, I picked up Calypso at her grandparents. We drove to her mom’s to get her scooter and go to the park. The building superintendent asked where we were going. I told him, and seeing a puzzled look on his face, asked why. He motioned me away from Calypso and whispered there was a knife attack in the centre of Nice and at least one person was dead. (Eventually it was learned that three people had been killed in the brutal attack.) We played in the nearby park for a few hours and had lunch from one of Calypso’s favourite take-aways.

And then, the moment of truth. Another decision.

I kissed Calypso goodbye and drove to Genoa, where friends offered an empty flat for me to isolate and weather the storm. A complete renovation, which had been put on pause the year before, had left a mess. While they apologized for the disarray, I rejoiced in having a place to stay and a project to keep me from losing my mind.

I am now in the process of cleaning construction debris, vacuuming, mopping, and setting up the flat. Gas is not connected, so hot showers are just like in the van—boil some water, mix in a bucket and bathe. And my camp stove has migrated indoor for the time being.

Everything is here to complete the flat, and as soon as I get through 50 layers of dust, I will embark on that project.

I am an optimist: the glass is always half full. I was blessed to meet Dann and park on his land, blessed to have friends in Genoa with a flat and, blessed with good health. I am blessed that my daughter and her mom are healthy and safe in Nice.

When we come out the other side of this monumental moment in time, when distancing is no longer obligatory, I will embark on a project to hug everyone I see. Meanwhile, I use the three most important words every time I speak with my friends and family: “I love you.”

Never forget to share these words with those who are important in your life because even though the glass is half full, it can always shatter.

For More from Tim go here.