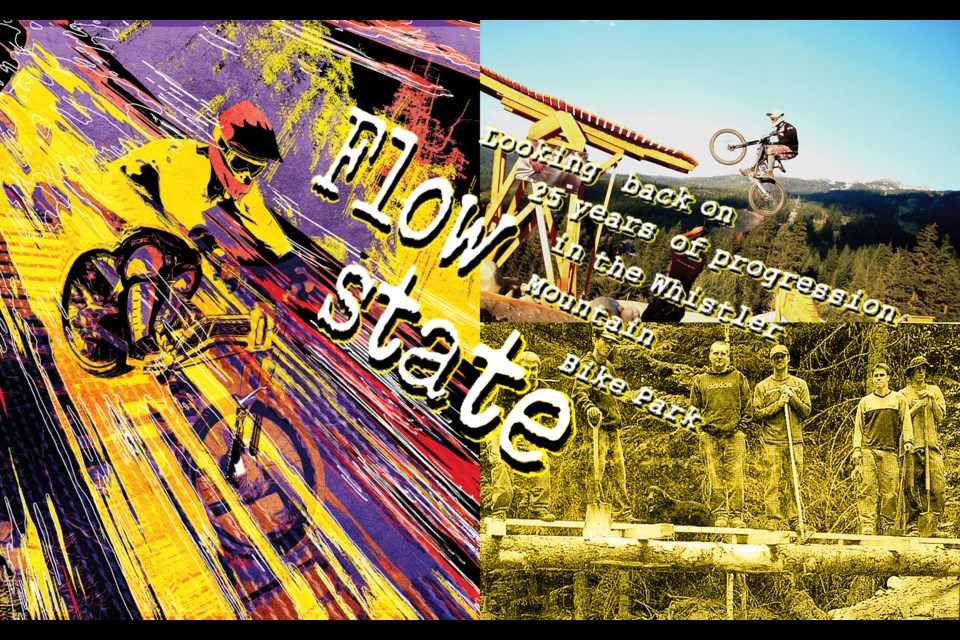

After a quarter century of operation, the Whistler Mountain Bike Park (WMBP) has evolved beyond lift-accessed trails; beyond skiers and snowboarders looking for summer activity; beyond world-class alpine riding. The Whistler Mountain Bike Park is an institution. Born out of ambitions to ride down mountain access roads and ski slopes, the WMBP now loads bikes onto five different lifts on Whistler Mountain during peak season. There are more trails, more types of trails, more vertical drop, and more people coming from all over the world to check Whistler off their mountain-bike bucket list than ever before.

The WMBP has raised a generation of local athletes who are winning UCI World Cup events. It operates one of the largest women-only mountain bike school programs in the world. It’s the birthplace of Crankworx, which continues to show the world what the world’s best can do on bikes. When it comes to bike parks, nothing really compares to Whistler.

Humble beginnings

The 25-year anniversary of the WMBP may befuddle some local bike veterans, since the historical record states Eric Wight was leading bike tours down routes on Whistler Mountain—accessed with the Whistler Village Gondola—in the mid- to late-1980s through his guiding company Backroads Whistler. Although the name “Whistler Mountain Bike Park” was bandied around at the time to help sell gondola-accessed bike tours, it wasn’t a real bike park yet. You had to sign up for a tour and be led down the mountain by a guide, understandable given the average rider skill and bike technology back then.

By 1999, Backroads employees like Dave Kelly had built a handful of singletrack trails between Olympic Station (Whistler Gondola mid-station) and Whistler Village. These included trails still on the map today: Fantastic, Crabapple Turns, Ho Chi Minh and Crack Addict (now known as Pulp Fiction).

“It was clear mountain biking was on a fast growth trajectory” says Rob McSkimming, former vice-president of business development at Whistler Blackcomb. “We’d been running bikes on the Blackcomb lifts, we had a partnership with Backroads on Whistler Mountain, we had some rental, retail and repair services in place. We had to pause the bike tours on Whistler while we installed the Fitzsimmons Chair. So that summer, we had time for a discussion on whether we wanted to get into this business in a bigger way.”

McSkimming and his team made the business case for a lift-accessed bike park, utilizing the brand-new, high-speed chair from the Village base area. With the team’s experience in ski-school operations, guide and coaching services were made available, but weren’t mandatory for visiting mountain bikers. The proposal was reluctantly approved by Whistler Blackcomb’s management, with two clear aims: it had to be a viable business (i.e. not lose any money) and it had to address safety concerns.

“We were under pressure to make it work in those first couple of years, like with any new ideas back then, summer or winter,” chuckles McSkimming. “Having that drive was one of the things that helped make it successful. [WB management] weren’t willing to invest in the bike park just yet, so we got our budget by adding $3 onto the price of a sightseeing lift ticket. That offset the cost of trail maintenance and additional patrol.”

McSkimming estimates the first summer of the bike park had somewhere between 11,000 and 18,000 visitors. While $3 per visitor doesn’t sound like a lot today, it went a lot further 25 years ago. With the first year more than covering the costs of operating the bike park with the ticket surcharge, the overall ticket sales were up as well, another feather in the cap of the burgeoning bike park.

“By 2001, it was like, ‘whoa, this thing’s on fire,’” says McSkimming, of the WMBP’s rapid rise in popularity. “The conversation shifted from proving it was viable, to how to best manage it moving forward and where to invest in it. It shifted pretty quick.”

Finding the flow state

One such strategic investment was in machine-built trails, a new concept at the time. A-Line is still the trail that receives all the fanfare, but one could argue its predecessor B-Line has done as much—if not more—for the sport of mountain biking. B-Line was the first trail built using machines like mini excavators and skid steers, letting trail builders build and maintain more trails, faster.

“(B-Line) was the start of what really changed bike parks and trail development around the world,” says Wendy Robinson, WB’s senior manager of business development and planning, who worked under McSkimming for a large portion of her career. “A-Line was obviously a huge success and led to the trail crew developing more jump trails. This was a major attraction for riders, because they couldn’t find trails like this anywhere else.”

Having a playground for advanced riders boosting massive jumps is great for publicity and word-of-mouth in the core mountain-bike community, but to make a sport sustainable, you have to make it accessible for new entrants. When Robinson started guiding in the bike park in 2002, her options for coaching beginners were pretty much B-Line or the mountain road. B-Line was of course much more fun to ride, and subsequently, much easier to teach on. It was eventually reworked as a blue intermediate trail once the even-more-beginner-friendly Easy Does It trail was commissioned, but B-Line was still one of the most popular trails in the bike park. A-Line’s jumps required the requisite advanced skills to corner with speed and clear the tabletop jumps, which were—and still are—quite large. B-Line was the trail where riders could build skills, speed and confidence with constant repetition, without committing to scary-sized jumps or having to constantly overtake beginner groups.

The secret sauce to flow trails was advanced riders could have as much fun as intermediates by doubling up small jumps and riding more playfully. Novices could learn when to brake, and more importantly, when to let off the brakes and keep their momentum through corners and small berms. The wider, smoother nature of the trail lent itself to having more pullout spots where riders could rest or instructors could pull over to teach their lessons without getting in the way of rider traffic. It all seems quite remedial nowadays, but back then it was revolutionary.

“B-Line was great in so many ways,” says Robinson. “It took the pedalling out of the equation, because you had the lift access and gravity on your side. Riders could hone their skills on it no matter what their ability level. It changed the way we could ride mountain bikes.”

The only way is up

With the (original) Fitzsimmons Chair playing an integral role in the bike park’s early success, it was only a matter of time before eager trail builders began to scratch out trails in the Garbanzo Zone, connecting an additional 832 metres of vert on top of the Fitzsimmons’ 332 metres. Even with a smattering of blue flow trails added over the years, Garbanzo still maintains its reputation as a high-vert playground of technical singletrack. Trails such as Original Sin, In Deep and Fatcrobat are legendary in the global community of downhill riders and racers, and were featured in timeless MTB films such as The Collective’s Seasons.

The gruelling Garbanzo DH is still a hallmark event at Crankworx Whistler, the seven-kilometre descent referred to as a “downhill race for the bold, brave and borderline masochistic.”

Even with more vertical than most—if not all—lift-accessed bike parks in the world, McSkimming set his sights even higher for the WMBP. Bikes had been photographed on the mountain roads in the alpine for decades, but a true mountain-bike descent from the peak of Whistler was yet to be realized.

“It was a bit of a hard sell internally [at WB],” he says. “It was a bit of history repeating itself, with questions like, ‘do we really want to spread the operation out that much?’”

But mountain biking was evolving again. The enduro scene had gained traction in the high mountains of Europe, with riders seeking more adventurous big alpine laps. WB wanted to make sure it was staying at the forefront. That manifested with the Peak Chair-accessed Top of the World Trail.

“For our business to continue to grow we needed to make sure we were offering the full breadth of experiences to the various segments of the mountain bike community,” says McSkimming. “If we had stayed only in ‘jump world,’ we may not have had the longevity we needed. The peak of Whistler is just so spectacular, and it provides access to some really amazing riding experiences just below the alpine and now even outside the boundaries of the bike park.”

After extensive environmental consultation, careful planning and building (including the services of stone mason and former Whistler Mayor Ken Melamed), Top of the World opened to the public in 2012. Just like the opening years of the bike park, the budget was derived from a ticket surcharge, but the condition was Whistler Blackcomb would only let 100 bikes up the Peak Chair per day in order to minimize impact on the sensitive alpine environment. Top of the World is likely the most photographed trail in Whistler, adding yet another attraction pulling riders from all over the globe.

The next phase

The next significant trail expansion for the WMBP could have gone either of two ways. One option was to link adjacent terrain into the Creekside Zone, the other to create an entire new network on Blackcomb. While both options had their pros and cons, ultimately Creekside made the most sense.

“It was a huge decision, and not an easy one to make,” says McSkimming. “Neither [Blackcomb or Creekside options] were perfect. Terrain was a big consideration, but it was also about trying to breathe some life into the Creekside base area during the summer.”

The Creekside Gondola and the multi-level parkade weren’t being used to their potential during the summer, and Creekside businesses were lobbying for the development in hopes of increasing foot traffic in and around their shopfronts. The bike park officially opened its Creekside base in 2017 with the now-defunct Dusty’s Descent trail, which was built to tide riders over until more trails were completed.

“I feel like we really cracked the code for Creekside last year,” says Robinson. “We had a massive plan for that area to build new trails, as well as stitching together existing ones like Ride Don’t Slide and BC’s Trail. The pandemic slowed down the work a bit, but with the new singletrack to complement the blue flow trails, plus a new jump line on Insomnia, we now have over 25 kilometres of trail in Creekside. It’s like a bike park in itself. With all the rental and guest services amenities at the base it can basically operate independently of the Village.”

The road to the World Cup

The theme of the WMBP’s 2024 marketing campaign is “25 Years of Progression,” and nowhere is this more evident than with the rising youth stars of downhill racing. Sea to Sky locals Finn Iles and Jackson Goldstone have both chalked up elite men’s wins on the UCI World Cup circuit, and both honed their skills and speed on the trails of the WMBP. Jesse Melamed (who claimed the overall World Cup Enduro title in 2022), was a fixture of the bike park’s weekly Phat Wednesday race series, and still participates when he’s home from his busy race calendar.

While an official bid to the UCI for a World Cup or World Championship downhill event has yet to materialize, the ingredients are all there. During Crankworx in 2023, organizers hosted the Canadian Open Downhill race on the new 1199 track, which runs from the top of the Creekside Gondola to the timing flats on Dave Murray Downhill. The race was a resounding success, with elite downhill racers from all over the world commending the quality, steepness and speed of the track.

“All the way back from Rob’s (McSkimming) era, he was pushing to host a World Cup mountain bike event in Whistler,” says Robinson. “That put us on the path to build 1199. Whether we hosted a World Cup or not, we wanted a track of that calibre that wouldn’t have a major impact on the bike park’s operation when we raced on it. When we had the trail route planned, we walked down it with a bunch of World Cup riders and asked them, ‘if you were racing on this, what would you like to see?’ We gathered that feedback and made adjustments. From what we heard from riders at the Canadian Open last year, 1199 is a World Cup level track.”

Progression is addictive

Whistler is a town of adventurous outdoor pursuits, and when people get good at those activities fast, they tend to go all-in. No one knows this more than Whistler resident Dean Olynyk, who rides more days of bike park than anyone else. He first rode the WMBP in 2011 when he was still living in Vancouver, and instantly made the decision to sell his quite-new trail bike and bought a downhill-specific rig. Olynyk was hooked.

“I still remember the first time I rode Crank It Up, I was screaming like an excited child. It just sang to me,” he recalls. “I got faster and faster and I moved up to bigger and bigger jumps. The progression was just crazy.”

By 2016, Olynyk was striving to ride as many days of bike park as he could. On weekdays his schedule allowed him to start work early in the morning, break for a few morning park laps, return to work for a few more hours, then back to the bike park for evening laps. Weekends consisted of as many laps as possible as soon as the Fitz Chair loaded until the crowds arrived. In 2022 he rode all 136 days of the season, a goal he’d been striving for since 2016.

“My favourite trails are Crabapple Hits, A-Line and Dirt Merchant,” says Olynyk. “There aren’t trails that really exist anywhere else, and you certainly can’t get four laps of that in little over an hour without a high-speed chair lift. And all that within a few minutes’ drive of my house. I can’t wait to get back.”

After 25 years, the WMBP has made its mark on millions of mountain bikers around the world. Riders make their pilgrimage to Whistler to check it off their bucket list. Travelling trail builders get inspired by the WMBP, and bring the style and character of Whistler to trails in their home regions. But its biggest contribution is turning new riders into good riders, and good riders into great riders. The progression won’t be slowing down any time soon.

The Whistler Mountain Bike Park opens on May 17, featuring the new high-capacity Fitzsimmons Chair bike racks. This season riders can view an historical exhibit named “Park Lore” in the Children’s Learning Centre, next to the top of A-Line.