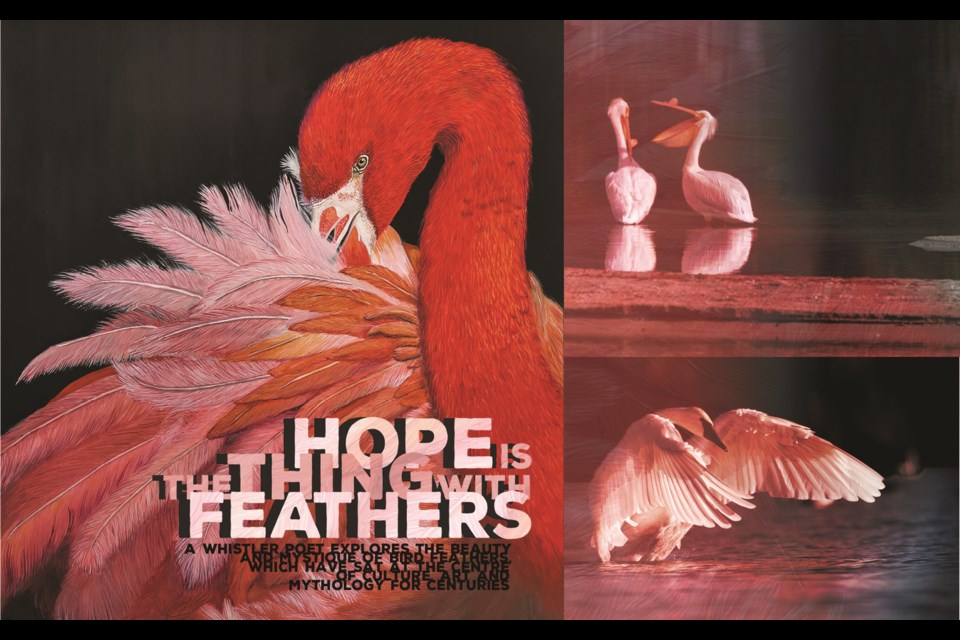

“Hope” is the thing with feathers-

That perches in the soul-

And sings the tune without the words-

And never stops—at all-

-Emily Dickinson

To Emily Dickinson, feathers embodied hope. They allow a bird to fly, to regulate body temperature, to protect itself and its young from predators. Ultimately, to be free.

A Moveable Feast

Last Christmas, I went for a walk in the woods and around the pond near my house. Not just any walk. It had been a year of losses, losing people I love, and I was looking to see if any meaning could be found. There was a foot of snow on the ground and the day was overcast, absent of that bright winter light. I locked the door and stuffed the house key deep into the pocket of my coat and headed downhill, carrying my gloom. I walked into the natural world, which to me, was heading home. Despite myself, I took comfort from the words of poet, novelist and environmentalist Wendell Berry: I come into the peace of wild things.

Our bodies are wired to respond in a positive way to nature. “There is mounting evidence that nature has benefits for both physical and psychological human well-being,” says Lisa Nisbet, a psychologist at Trent University in Ontario. “You can boost your mood just by walking in nature, even in urban nature.”

So, off I went, to be nurtured by nature. Before long, there were birds spilling from the woods

First a spotted towhee, a dark-eyed junco, and a clack-capped chickadee in the low shrubs following the creek. There were red-winged blackbirds. A chorus of them high in a red alder tree. Song sparrows and golden-crowned sparrows, and even a fox sparrow literally dancing in and out of the shrubs and woody debris in the riparian zone. There was a Bewick’s wren with its distinctive long, white eyebrow, hopping from branch to branch. All of them flying, upstroke and downstroke, swooping, soaring, and gliding as though they owned the woods and the pond. As though there were no people here. And save for me, there were none. It was as though the birds had taken back the land. They were rewilding and it was astonishing to see.

The birds weren’t hiding, the usual way they camouflage themselves so well in foliage. I was quiet as they sang, gathered in groups squawking, hopping along the grass in the open field. A heron walked along the gravel path beside me. I could not believe what I was seeing. It was an otherworldly kind of day. Then the perfection of that beauty taking flight. How do they do it? Making it look so easy.

The power was all in the feathers. Soon, I was thinking of lifting off too, flapping my wings, stirring up air.

The human desire to fly goes back to the Ancient Greeks—to the myth of Daedalus and Icarus. Daedalus, the inventor, secretly created wings made of feathers and wax to escape imprisonment on the island of Crete, where he and his son Icarus were being held captive. Icarus, however, flew too close to the sun. His wings melted and he fell into the sea and died.

Leonardo da Vinci sketched plans for helicopters, gliders, and parachutes. Inventors have made hang gliders, trying to fly. Surveys indicate that most humans dream about flying at least once in their lifetimes.

So, I am not alone in my desire to grow feathers and fly. In his book Bird Sense, ornithologist Tim Birkhead imagined what it would be like to be a swift, flying more than 100 kilometres an hour. It seems some of us humans have wing envy. But mostly, we can’t fly because we don’t have feathers.

Birds are the Only Animals with Feathers

According to Pulitzer Prize-winning science journalist, Ed Yong, in his 2022 book An Immense World, feathers are the genius of birds.

Yong wrote that the feather is an extraordinary biological invention and the key to modern birds’ success. “It must be light and flexible to give birds fine control over their airborne movements, but tough and strong enough to withstand the massive forces generated by high-speed flight.” The bird achieves this through a complicated internal structure that we are only just beginning to fully understand.

Bird feathers evolved, and fossil evidence suggests, that baby birds may have descended from dinosaurs. Science writer Carl Zimmer said, although early feathers weren’t always as efficient as they are today, scientists have found dinosaurs with remnants of feathers. Though, given their size, dinosaurs did not use their feathers to fly.

Just admiring the birds in the park, I would never have guessed the volume of feathers each bird carried. Songbirds, such as chickadees, sparrows, kinglets, and wrens, have between 1,500 and 3,000 feathers, while eagles and birds of prey have 5,000 to 8,000. Swans are the heaviest-dressed birds, with as many as 25,000 feathers. Interestingly, hummingbirds have the fewest feathers of all, at about 1,000. And penguins sport the densest feathers, with about 100 per square inch.

I thought of how little I knew about feathers. They keep a bird warm, control body temperature, protect the bird from wind and sun, aid the bird to swim, float, and in the case of the grouse, even to snowshoe. They aid in foraging, aid in controlling parasites, and they are used to construct nests. Birds being attacked can molt, or drop tail feathers, to get away from their attacker. They allow the bird to blend in and thus keep them safe from predators, and to catch prey. The more I learned, the more I understood they are much more than a thing of beauty. I was on the verge of wanting to be a bird.

Feathers Foster Flight—and Much More

In 2020, David Sibley, the American ornithologist, published a stunningly illustrated book, What It’s Like to be a Bird, in which he describes feathers, bird by bird.

Of course, there are wing feathers, down feathers, and tail feathers. The bird also has contour feathers, semiplumes, filoplumes, and bristle feathers. All feathers are important structurally and functionally for the bird. Each provides an important role for the bird’s activities. The primary role of feathers, of course, is flight. But it is far from their only function.

The wing feathers are the most perfectly designed structure the bird possesses. They are both lightweight and flexible, but also rigid enough to help the bird lift off the earth to fly, dive, swim, land, and travel for miles during migrations. Feathers protect the bird from the elements, they repel water, provide camouflage, and with their showy bloom displays, they also attract mates. And feathers are renewable—when damaged a bird can do a repair mold, shed, and make way for new growth.

What is it About Feathers?

And look at all the ways we use feather metaphors in our everyday speech: Put a feather in your cap. Light as a feather. Birds of a feather. Feather your nest.

For humans, bird feathers are at the centre of culture, art, and mythology. They constituted courage in battle, strength, artistry, and sacred objects. They have also been important in decorations and fashion.

Feathers are used today to make warm bedding, including eiderdown, and in winter clothing. Eider can trap a large amount of air for its weight. Feathers were also used for quill pens, fletching for arrows, and to decorate fishing lures.

I asked Whistler’s Maeve Jones about feathers as jewelry. About 10 years ago, Jones had worked with pliers, scissors, and glue to create entirely unique feather earrings. At the time, feather jewelry was in fashion and the earrings were celebrated gifts to friends. Something about the colour and wispy dance of feathers was clearly special.

Then, Jones began to observe feathers in the natural world. Working with feathers enlightened her relationship to the birds, and eventually she became more interested in birds in their natural habitat. “I remember a yoga teacher speaking once about how in many Indigenous traditions, birds are viewed as messengers from god,” she says. Soon, Jones found she cared less about the feather jewelry and more about the birds. As her curiosity grew, she found herself evolving, coming closer to the source, towards a deeper understanding.

Feathers also symbolize a connection to the spiritual world. I wanted to know more about this. What did poet Emily Dickinson mean, hope is the thing with feathers? And why was a great blue heron, a bird that tends towards solitude, walking beside me that day?

So, I sought out someone I hoped could help, Lil’wat Nation storyteller Tanina Williams, owner of amawílc, a consulting company that teaches Indigenous ways of knowing.

“Eagle feathers are very important to Indigenous people,” she says, “and to Lil’wat people in particular.”

I asked more about feathers and what they mean to Indigenous peoples. I wanted to know about eagle feathers.

“When you gift an eagle feather,” she says, “you are telling that person that you have arrived.”

Not necessarily that you’ve arrived in your whole life, but you have you have reached an important moment in time. “The feather means keep going forward.”

She told me a story about wanting an eagle-feather fan, but never finding the right time to obtain it. There was something in her that resisted, despite wanting the fan. “I was resisting, until one day, it was the right time. I had been resisting becoming recognized as a spiritual leader.”

In time, she accepted the honour of the eagle fan, and from that day forward, felt her path became clear.

“Every living thing is beautiful,” she says, “but the eagle feather is held in such esteem, it cannot be dropped.”

She learned from her own elders that the eagle feather has this meaning because of the heights the eagle can reach, it being closest to the creator.

Even a young person in Indigenous culture can be an elder—“The way every feather has a purpose and even small feathers, like down feathers, do a big job,” Williams says.

The feathers give good medicine too, but the path isn’t made easy. All people must do their own work. So, learning is taught, but is also energetic. When the learning is done, the feathers, having completed their job, can go back to the Earth.

We both got carried away talking about our shared belief that the bird world occupies some liminal space between our material world and the world of the hereafter. A space we don’t fully understand, and don’t have words for. Like whom or what was beside me that day, embodied by the heron? That’s when Williams told me that her first name means, “the last star that goes up before the sunrise.” That seemed like a good place to end our conversation, for now.

Murderous Millinery

I wrote a story about a white-throated sparrow who was orphaned by its family in the north of France during the First World War. Shrubs and low bush were flattened by tanks. Habitats were destroyed.

In my story, the sparrow flew all the way to the dormer of a window in the Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris, and a milliner who had stitched hats out of exotic feathers.

It was this headwear craze that led to the mass slaughter of birds. Ostrich, the great white egret, peacocks, and heron plumes were sought after by the fashion industry.

In the 1700’s, Paris had 25 master plummasiers, craftspeople who work with ornamental plumes. Only a century later, there were hundreds. In London, U.K., the fashion feather market went through nearly one-third of a million white egrets in 1910 alone.

The ornithologist, Florence Merriam Bailey, wrote about the fashion trend of using exotic feathers in ornamenting women’s hats. She said that on one walk through the Manhattan fashion district in 1886, she counted 40 different species, stuffed, and mounted for fashion. Bailey wanted to stop this trend, which killed an estimated 5 million birds a year. Her solution was to teach people to admire the living bird.

At the time, ornithologists were most interested in studying birds that had been killed, skinned, and mounted for private or museum collections. Bailey proposed that naturalists should learn to observe living birds in their habitats. Her 1889 book, Birds Through an Opera Glass, was the first modern birdwatching field guide. Bailey was named the first woman associate member of the American Ornithologists’ Union in 1885. Today, she is recognized as an author of exceptional works about birds.

In possession of one final hat, un chapeau de regret, the Parisian milliner in my story hid the hat in a box under her bed, hoping to forget the birds who had given up their lives for her fashionable hats. For times had changed. The status symbol of fashion had turned to a humiliation.

The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 had been signed into law by U.S. President Woodrow Wilson. Canadian law soon followed, put into place to protect migratory birds due to fashion and over-hunting that was threatening species.

But it wasn’t until February 2021 that Paris city council agreed to end the live bird market operating on the Île de la Cité. A closure that at long last answered the calls of animal rights activists who considered the market a cruel and archaic operation.

Though nothing this attractive ever really dies. Even today, there are plummasiers in Paris, creating haute couture from feathers. As though they cannot help themselves. “It’s like an animal transforming into a woman,” declared Charles-Donatien, a Parisienne artisan who still designs clothing with feathers, in a 2017 New Yorker article. Fashion houses today use antique feathers, dyed and hand-painted feathers, and feathers tailor-made of cloth.

Our Duvets and Down Jackets

There is no such thing as being too warm during a Whistler winter. And down is the most common feather used in fashion today.

The most superior down, and arguably most sustainable, is eiderdown, which is considered the best, most insulating down in the world. It is sourced from common eiders, a group of migratory sea ducks that live in very cold northern coastal regions of Europe, North America, and Siberia.

Recently, sustainably minded companies such as Patagonia have begun to invest in recycled down, which diverts old cushions, comforters, and pillows from the landfill by repurposing the down into new coats.

Colonies of eiders in Iceland and Canada are cared for by humans, who carefully harvest down from nests with as little disturbance as possible. But here’s the rub: an ethically sourced eiderdown comforter can cost upwards of $15,000.

Besides, is there really any such thing as ethically sourced down? Eider is taken either by a feather-picking machine or from the bird manually. It can be plucked from a live bird, considered by some to be sustainable. But the evidence suggests otherwise; plucking can cause pain, bleeding, tearing of the skin, and distress to the bird.

Research scientists are using feathers to learn more about the impact of human activity on birds. Ducks Unlimited Canada is in the fourth year of a five-year study of feathers from waterfowl in highly disturbed areas, as well as remote, untouched spaces. By analyzing the stress hormones present in feathers left by waterfowl in both disturbed and undisturbed areas, and comparing them, researchers will be able to assess the impact development can have on population dynamics. The feathers will tell the story.

Fly Fishing

One day, I was watching two men fly fishing, standing in the water at the mouth of the river on Green Lake, when a nearby walker called out, “How’s the fishing?”

One of the men called back, “The fish are safe.”

It struck me then that fly fishing has something in common with birding. It is meditative.

By the time I found James Prosek’s book, The Complete Angler, which followed in the footsteps of Izaak Walton’s similarly named 1653 tome, The Compleat Angler, I wasn’t surprised that he considered “the theatre of nature to be his house of worship.” I had already heard him interviewed where he described falling in love first with birds, then with fish, and particularly with trout. It all began for Prosek at the age of nine, when his mother left, and he sought solace on the river.

My father was a fly fisherman. I accompanied him as a child, and I believe those early adventures on a river, like Prosek’s, launched my connection to the natural world. Standing in the river, trying to do what my dad was doing. Without much luck. Our days passed in silence. Always admiring which fly he would choose on a particular day, and why.

Inevitably, my fly-fishing questions led to The Feather Thief, a 2018 book by Kirk Wallace Johnson, primarily about fly tiers and the theft of exotic feathers. In June 2009, Edwin Rist, a 20-year-old American studying at the Royal Academy of Music in the U.K., smashed a window at the British Natural History Museum at Tring, near London. Apparently, Rist stashed the preserved skins of 299 tropical birds in a suitcase, birds that had been collected by the naturalist Alfred Russell Wallace in the mid-19th century. After he was arrested, Rist, an expert fly tier himself, said that he intended to fence the birds to fellow fly tiers to raise money to support his career and his parents’ struggling business.

I was struck by Prosek’s comment that “trout are opportunistic feeders and generally will eat anything they can get their mouths around.” It may be that feathers from rare and exotic birds, now banned, don’t really make more efficacious flys.

According to Johnson, fly-tier forums still talk about collecting and possessing rare and banned feathers. But it is illegal to possess feathers from most birds. According to the law, there’s no exemption for molted feathers or from those taken from roadkill birds. Even today, a black market exists for exotic feathers, such as Indian crow, chatterer, herons, and cockatoo.

Whistler, The Fly Way and Trumpeter Swans

In 2022, Whistler was added to the BC Bird Trail, a series of self-guided birding tours throughout the province. It is a recognition that we lie in the pathway of the Pacific flyway, a major migratory thoroughfare. In the fall, adults and their young are moving south, and in the spring, they’re returning north. We host about 100 species passing through annually. Whistler is a hot destination for birding.

A highlight is the trumpeter swans, especially important to us in Whistler. All you must do, in the next few weeks, is wander down to Green Lake to see these elegant birds stopping here on their way back to Alaska.

With a wingspan of seven feet and a weight upwards of 25 pounds, trumpeter Swans are North America’s largest flying birds. Their long necks allow them to access food in deeper water than other waterfowl; they can upend and uproot plants in four feet of water.

At one time, however, trumpeter swans were on the brink of extinction. By the 1930s, due largely to overhunting, there were fewer than 100 adult trumpeter swans left in Canada. Domestically, trumpeter swan skins were marketed especially by the Hudson’s Bay Company. The swan feathers were popular as a glamorous addition to fancy hats and as quills for ink pens. More than 1.2 million quills made from swans and geese were sold in London in 1837 alone. At least 100,000 swans and geese were required to make that number of pens. It is not surprising that the population of North American swans plummeted.

Today, trumpeter Swans are protected, and their numbers have come back to approximately 16,000 in North America.

We are Part of an Ecosystem

We have lived our lives by the assumption that what was good for us would be good for the world. We have been wrong. We must change our lives, so that it will be possible to live by the contrary assumption that what is good for the world will be good for us. This requires that we make the effort to know the world and to learn what is good for it.

- Wendell Berry, The Art of the Commonplace

As humans, we now face an environmental crisis, but I think, also, a moral crisis. We have triumphed over species, such as birds, at our own peril. Accepting our place in the ecosystem, as one among many, won’t be easy.

Author James Bridle in his 2022 book, Ways of Being, talks about “the broad commonwealth of life.” Everything in nature is equally evolved. It is a notion that destroys any idea of hierarchy.

Robin Wall Kimmerer, author of 2020’s Braiding Sweetgrass, said, “I can’t think of a single scientific study in the last few decades that has demonstrated that plants and animals are dumber than we think. It’s always the opposite.”

This requires a shift in awareness. By letting our various encounters, not only with birds, but with trees, rivers, all the natural world to sit with us. As Bridle says, “In a way it is our ability to live with the unknown and the unknowable.”

It was interesting to see in Barry Lopez’ final and posthumous 2022 book, Embrace Fearlessly the Burning World, he considered his calling spiritual. “Perhaps the first rule of everything we endeavour to do,” the nature author and environmentalist writes, “is to pay attention.” And paying attention is radical and deep. He urges us to give non-humans their due, not as resources to exploit, but as a web of interconnected beings, “each with their own integrity and perhaps even their own aspirations.”

It is as though all relationships with the natural world lead ultimately to a relationship with the divine. Why was I walking to be in the company of birds when my soul felt devoid of hope? And how was it possible a great blue heron walked, literally, beside me. Changing our behaviour seems hard to do. It might be easier than we think.

Later, on Christmas Day, when I reached the front door of my house, and rummaged for my house key, my pocket was empty. My house key must have fallen out of my pocket and into the snow. Suddenly, I could feel the wild thumping of my heart. There was no point in going back. Finding the key in a foot of snow somewhere on a long walk would be impossible. I took my time, before calling the one person I had given a key. Gusts of wind had come up and it was near dark. For a brief moment, I knew the fear of being outdoors without the safety I had come to know and trust. Some part of me wanted to feel this tightness in my chest. Some part of me, I barely know, was unafraid.

Mary MacDonald (marymacdonald.ca) is a writer and holds a PhD from the University of British Columbia. Her book of short fiction, The Crooked Thing, is available from Caitlin Press and locally at Armchair Books. She sits on the board of the Whistler Writers Society and is curator and moderator for poetry at the Whistler Writers Festival.

This is a companion piece to her September cover feature, “Adventures in Birding: When a Walk Becomes More than a Walk.” Read it at piquenewsmagazine.com/cover-stories/birding-adventures-whistler-bc-5853530.