[This story contains adult language and subject matter.]

“Civilization: a scheme to hide nakedness.”

-Marty Rubin

Micheline Syvret has just arrived in Whistler to visit her son when she calls him to let him know she’s here.

“I made it,” she says. “I’m at Lost Lake, on the dock.”

Knowing full well where this is going, her son, photographer Jeremy Allen, asks her which dock she happens to be on.

“It looks like a giant cross,” she replies.

“Oh, the nudie dock?” he asks.

Taking in the wholesome lakeside scene—families picnicking on the shore, rambunctious dogs zooming around, solitary fishermen waiting for a bite—Micheline is surprised. But not as surprised as she is about to be.

“It goes quiet for a couple seconds on the phone,” Jeremy remembers, “and then I just hear, ‘OH!’ She looks over and there’s an old man bathing naked.”

“I guess it is the nudie dock,” she concedes. “Shit.”

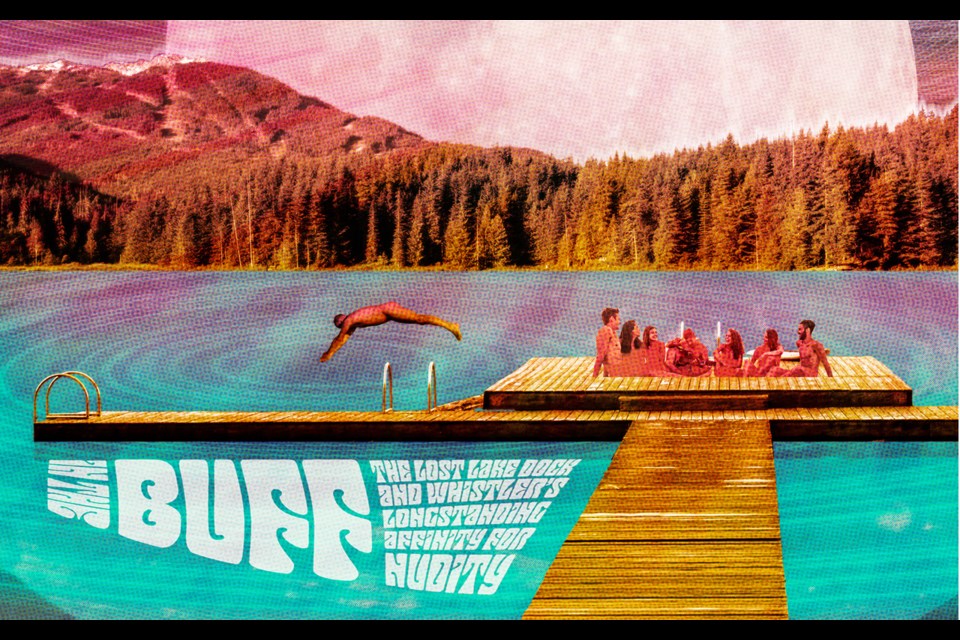

Micheline is not the first person to be confronted with the naked truth of Whistler’s time-honoured nudie dock, and she surely won’t be the last. First cobbled together in the late ’70s by a crew of resourceful freestylers who wanted some aerial jumps to huck themselves off of in the dog days of summer, it quickly became a nexus for Whistler’s ski bums, hippies and burners, a place where, in those days at least, pretty much anything was acceptable, as long as you weren’t a dick about it. (A figurative dick. Literal dicks were OK.)

It wasn’t uncommon to find national-team skiers soaring off these DIY jumps as a crowd of supporters looked on in their birthday suits. In fact, sometimes the more daring skiers would be in the buff themselves.

“Some of the freestylers would jump naked, too, but it wasn’t advisable. It really hurt,” says former ski coach Dave Lalik, one of the four Daves—along with Young, “Airman” Brown and Wallin—who were the driving force behind building the dock.

Although the original dock has long since been torn down, you can still find gaggles of locals happily ditching their clothes at Lost Lake, a small reminder of the free-wheeling ethos that Whistler was founded on that persists in subtle ways today, even as a world-class resort has been built up around it.

Whether it’s the ubiquitous Toad Hall poster, the infamous Boot Ballet or the legendary documentary Ski Bums depicting the community’s late-‘90s dirtbag culture, Whistler has a deep affinity for nudity, and in many ways, it’s the Lost Lake dock that has served as its spiritual core.

“Whistler has a long history of nudity and really it comes back to that Lost Lake dock,” says Johnny Thrash, who many Whistlerites of a certain era have probably seen more of than they ever expected.

But we’ll get to that.

Letting it all hang out

As was often the case in Whistler’s hippie era, the Lost Lake dock began with a kernel of an idea and the stubbornness to make it happen. When Lalik and his fellow Daves first set to building the dock, which was nothing more than a few logs from a nearby mill tied together with some plywood on top, they did so without any sort of approval from the powers that be.

“Build first and then apologize later,” Lalik says. “That was the theory back in the day, and that usually worked with some of the level-minded bureaucrats.”

Frustrated with the lack of summer aerial opportunities offered on Whistler Mountain, freestyle skiers by 1977 decided to build their own jump in the valley, but, according to the Whistler Museum, the newly formed Resort Municipality of Whistler (RMOW) and Squamish-Lillooet Regional District weren’t keen to hand out a development permit. Living up to its name, Lost Lake and its out-of-the-way location seemed an appropriate place to build the jumps under the radar.

In the kind of handshake deal that would seem virtually impossible today, Lalik says that once the dock was discovered, there was also a deal struck with the province—which still controlled the land in and around Lost Lake at the time.

“It was a loose agreement; nothing too formal,” he recalls. “If we helped out, put in culverts and worked on the road, we could use the space for our jumping.”

Projecting out six metres onto the lake, the ramp allowed ambitious skiers to launch themselves up to 12 metres over the water. Understandably, injuries weren’t unusual.

“It was scary as shit,” recalls Lalik. “Really, really scary.”

But even the prospect of injury couldn’t deter world-class skiers from hitting the ramp. By the ‘80s, Lost Lake hosted competitions and the first Summer Air Camp was held in 1982, attracting freestyle skiers from as far away as Japan to train, and showcasing Whistler’s popular dock on televisions near and far.

It represented an interesting confluence of elite athleticism and counterculture that still exists today, with dock regulars seeking their own personal form of freedom, whether it meant soaring through the sky at impossible heights, or achieving a different kind of high altogether.

“Whistler originally was people seeking alternative, unique lifestyles in a recreational place and a lot of freedom. The dock fit that bill,” says local Paul Fournier, a regular frequenter of the Lost Lake dock since the ‘80s. “It was just nice to go there and get the all-over tan and hang out.”

Admittedly more “out of the way” than Lost Lake is today, what with its short walk from the bustling village and free shuttles ushering tourists there more than two dozen times a day in the summer, it was probably for the best that the original incarnation of the dock was harder to find back then.

“At the beginning, if you got more than six people on the dock it would start to sink and they would have to go sit on the jump,” Fournier says.

Today, the new dock is in far better condition than those early days, after the RMOW tore down the original, along with the ski jumps, at some point in the mid- to late ‘80s, by most accounts. And then as in now, the nude aspect of the dock was something of an open secret, although for tourists and newcomers, there is still the chance of getting caught off-guard by a sunbather’s naughty bits.

That’s why Fournier has been pushing for the municipality to formalize the dock as a clothing-optional area, including recently erecting a handmade, wood-burned sign he put up himself to give visitors fair warning. The day after he put it up, it disappeared.

“Lost Lake is almost like the bastard stepchild of the park scene,” he says. “We’ve got all this other infrastructure created in all the other parks and you’ve got this crappy little trail access off the main trail to get down to the dock, and once you get down there, it’s the only place on Lost Lake where you can actually be on the water without being in it, unlike all the other lakes in Whistler … So it leads people to go there, and then there’s surprise and discomfort around [the nudity].”

For its part, the RMOW says neither the bylaw or parks department has a record of removing any signs, and one staff member recalls a municipal sign that was installed at one point that read something to the effect of: “Beware of Bares: Nude sunbathing area.”

It is admittedly a tricky balance to strike for municipal hall. Whistler is no longer the quaint little ski town that attracted misfits and squatters seeking an alternative lifestyle, but a multi-billion-dollar Olympic venue and international hub that means there is much more at stake. If signage is put up notifying visitors of the dock’s clothing-optional status, then, presumably, they’re inviting the kind of loose behaviour that was the norm 30 years ago.

But, at least according to Fournier, the Lost Lake regulars do a good job of policing themselves and encouraging the right etiquette.

“For a few years it was getting really wild. There was a group there that partied hard and was kind of wild. But it’s mellowed,” he says. “It’s a place where you don’t crank up your music; it’s more of a live-music vibe. Or you don’t come out and play volleyball on the dock or bring your kids running around yelling and screaming. There are other places to do that.”

Fournier and other local long-timers I spoke with feel like the dock symbolizes something deeper than just a chill spot to catch a few rays and have a good time. Not to sound overly dramatic or anything, but you can see how that tug of war between the laisser-faire free-spiritedness of the dock’s past and its more reserved, family-friendly present can stand in as a microcosm for the existential crisis that Whistler and other tourist destinations like it have experienced for some time now. How do you preserve the authenticity that attracted so many people here in the first place while still catering to a wider umbrella of visitors?

“For myself, I don’t know whether to laugh or cry because I’ve spent so much time fighting the establishment that I’ve become it. Whistler is somewhat like that. It’s more conformed. It’s not as freewheeling and open as it used to be,” says Fournier. “Young people didn’t need as much skin to get in the game. The game today has gotten more serious, that’s for sure.”

Full frontal

It goes without saying that the Lost Lake dock was by no means Whistler’s first, or even most recognizable, display of the human form. On a sunny spring day in 1973, a few years before the dock was built, Chris Speedie set his camera lens on 14 brave young souls sporting nothing but their smiles and ski boots in front of the iconic Soo Valley squat known as Toad Hall.

Today, the infamous Toad Hall poster hangs in dorm rooms and pubs from Whistler to Kitzbühel, a slice of the ski-bum lifestyle that so many have sought out, and others still yearn for. (For a deep dive into the making of the Toad Hall poster, check out Pique’s oral history, “Overexposed,” published Sept. 6, 2015.)

Impossible to predict at the time, the poster has become the spiritual ancestor to so many of Whistler’s revealing moments to come. You can draw a straight line from that iconic photo to Gary McFarlane’s line of Barely Whistler postcards, depicting locals engaged in a variety of sporting and recreational activities entirely in the nude. Running from 1992 to 2000, the idea for the concept came during a backpacking trop to Kathmandu a few years before. Hanging out with a couple of Aussie women he had met, McFarlane and a buddy got their hands on one of the women’s camera, and decided to surprise her with a shot of them in the buff wearing sunglasses. (Because I’m a hardworking and diligent reporter who wants to give you, dear reader, nothing but the facts, I should clarify: the boys wore their shades on their junk, not on their faces—think of an elephant in Ray-Bans, and you kind of get the idea.)

“A few months later, my friend randomly bumped into the owner of the camera on the streets of Sydney or Melbourne, one of the two. She said, ‘Oh my god, my mom developed that roll of film!’” McFarlane recalls.

Because she wanted more folks to experience the joy of this image, she handed over the roll of negatives. Another friend of McFarlane’s later asked to blow up the shot so she could shoehorn it into her own travel slideshow, “so that people who flipped through them only giving them a little bit of attention … would suddenly start to pay attention again.”

Well, that is definitely one way to grab someone’s attention.

It was a couple years later, when McFarlane was back in Whistler showing off his travel photos from a trip through Norway—which, you’ll be shocked to learn, also included a few dong shots—that an inebriated spectator suggested turning the nudie Judies into a full-fledged line of postcards, and just like that, Barely Whistler was born.

On sale at mom-and-pop shops across town, including Foto Source, where McFarlane worked at the time, the postcards—showing tastefully nude Whistlerites climbing, biking, windsurfing, rollerblading, and more—were a hit with both locals and tourists alike.

“It appealed to people who came to Whistler and were living there and wanted to, in a sense, brag about the place, to show everyone how crazy it was,” McFarlane says.

Then there was the legendary Barely Whistler closing party that packed nude and semi-nude attendees to the rafters.

“We had a couple hundred naked people in there, including a few people who probably never expected to do something like that in their lives” McFarlane says. “There was one table of ladies who were up here from Seattle, and they were just there to look. One of my more outgoing friends went over and she started talking to them, and next thing you know these ladies had all ripped off their shirts and bras and were partying topless. I bet they haven’t stopped talking about that to this day.”

Of course there’s no discussing nudity in Whistler without the Boot Pub, one of several resort bars that was home to exotic dancing over the years, and significantly, also host to the incredibly popular amateur nights that saw local guys and gals strip down to their skivvies for a little extra cash and shots of tequila.

“That was probably the highest grossing revenue of any night that we did,” says Paul McNaught, who managed the Boot Pub for several years before it closed in 2006. “We had line-ups outside to the car park at two o’clock in the afternoon even though our doors didn’t open until five.”

First opened in 1970 as part of the Ski Boot Lodge Motel, the Boot Pub quickly became the cultural and social epicentre of the town, and even in its later years, the venue reflected that fact. Far from being the kind of erotic entertainment you might expect from a strip show, McNaught says amateur night encouraged all-comers to get up and dance, no matter your gender or experience level.

“We had a very local contingency of people, from guys to girls. It really didn’t matter who you were,” he says. “They didn’t have to get fully naked. It was more like getting up there to impress … and if they tried to get erotic, sometimes they would make a spectacle of themselves. It was funny.”

Exotic dancing had a shelf life here, however. In 1999, the RMOW passed a bylaw banning stripping in all venues except for the Boot Pub, much to the chagrin of nightclub owners who hoped to cash in on Whistler’s burgeoning reputation as a ski destination. Capones, a bar that operated out of the current Moe Joe’s location, shuttered after a three-month fight with the municipality over its bid to offer exotic dancing on a nightly basis.

“We couldn’t fight them any longer. Muni put me out of business,” owner Dan Richardson was quoted in Pique at the time.

Even the Lost Lake dock wasn’t immune from Whistler’s evolution into a more sanitized resort. Around that time, after complaints mounted, sunbathers were threatened with prosecution if they continued to sunbathe naked.

It was also in 1999 that Johnny Thrash, who I think could rightly claim the title of Whistler’s streaker-for-hire, was arrested and forced into court-appointed therapy after touring around the village in a gyrosphere as naked as the day he was born, a jaw-dropping scene captured in John Zaritsky’s National Film Board of Canada documentary, Ski Bums. (It still blows my mind that the NFB, known by so many Canadian schoolchildren as the makers of many yawn-inducing educational films, put this movie out.)

The experience has had a lasting effect on Thrash, born John Hunt, who also produced the film.

“You can get in a lot of fucking trouble for it, which I found out. It was very, very serious and it was a very stressful time for me,” he says.

Believing the powers that be wanted to make an example of him, Thrash says he was placed in an alternative measures program, likely the first time an indecent exposure charge was funnelled into such a program. As such, he says he was required to write an apology letter and undergo four sessions of court-appointed therapy, at $350 an hour.

It wasn’t until friend and ski filmmaker Gary Stump got wind of the charge and enlisted the help of a high-powered attorney who offered to take on the case pro bono that the charges were ultimately dropped.

“The exact words that were used is that, ‘We must make an example of this guy.’ So there’s a dark side to this, too. I went through serious hell and anguish,” Thrash says. “In hindsight, would I do it again? I’d probably do it again but get the guys not to drive in front of the cop shop on the first pass.”

Thrash was not the first Whistlerite to experience backlash over exposing himself. World champion freeskier Rob Boyd was a regular in the pages of the irreverent alt weekly, The Whistler Answer, and in 1992, he was approached to help promote the annual Summer Love party, and was snapped in a cover shot on a sailboat while a bare-breasted woman, Nadine Stone, lay on the bow. Inside the same issue, there was also a spread with Boyd straddling a motorcycle naked (his stuff was airbrushed out, which he says “sorta made me look androgynous”) while Stone took a naked dive into the lake.

Relatively innocuous photos by today’s standards, Boyd—a local hero and town ambassador—took the brunt of the heat after a group calling themselves Mothers for Morality threatened to picket the Answer’s re-launch party. (The paper was briefly revived after its initial run from 1977 to ’82.) As a result, Boyd lost an endorsement deal with the Whistler Resort Association, the predecessor to Tourism Whistler. Although he concedes he lost “a good chunk of change” because of it, he didn’t lose much sleep over the controversy.

“I just said, ‘Ah, whatever. Get over yourselves. I’m going racing,’” he says. “I focused on my training and racing and … just kept doing what I loved doing. I didn’t let it get me down at all.”

The same couldn’t be said for Boyd’s mom, however.

“My mom obviously took my side and was quite offended by it,” he recalls. “She used to go hang out with Peter and Trudy Alder and with their Swiss background, Trudy would walk around the house topless. It was just the European thing to do, and I raced in Europe all the time.”

Proving the old adage that there’s no such thing as bad press, the backlash actually ended up putting more eyes on the cover and Whistler Answer after a Vancouver reporter penned a column in The Province “totally making fun of these ladies,” says Answer publisher Charlie Doyle.

“They never turned up and that was the last we heard from them,” he adds.

“You couldn’t ask for better publicity.”

End of an era, or a new kind of freedom?

By this point, lamenting the loss of Whistler’s bygone eras is as much a tradition here as going au naturel. Every generation of Whistler lays on the nostalgia thick, which is understandable in a community where development comes at such a breakneck speed that it can feel impossible to catch your breath.

Of course no community is immune to progress, nor should it be, and there’s no denying that Whistler has changed since those heady hippie days, for both good and bad, depending on your perspective.

But does that freewheeling spirit, that sense of freedom that is so perfectly encapsulated in the act of shedding our clothes, our masks, our walls, in the return to our natural state, still exist? Or is it that the definition of freedom has changed?

Let’s leave that to the one and only Johnny Thrash.

“All my buddies’ kids are super rad but they’re way more conservative than us. They grew up with us partying our asses off, and I think when they got to our age, they were like, ‘Fuck, I don’t want to be like my parents,” he says.

“It saddens me that things are like this these days, but there’s always hope. I bet ya there’s some kid who is out here from Ontario and he’ll be the next Johnny Thrash, and he’ll be playing in a band, wearing a skirt, and running around getting people laughing and out of their comfort zones."

A quick aside about my dad, the nudist

I don’t know if you’ve ever had a serious father-son discussion with your dad while his twig and berries hang loose, but in my case, that was a semi-regular occasion growing up. Needless to say, it made for some embarrassing moments in high school when I would bring friends over to the house, only to hear my dad scrambling desperately to lock the front door and put some clothes on before we came in.

“That’s what I do to this day. If I’m in my apartment, I’ll have the clothes right beside me, ready to go,” he says.

My father, in case you haven’t figured it out, has never been a big fan of clothes. To him, they’re basically a maximum-security prison for his body that he longs to break free from. As he tells me one sunny morning enjoying a fully-clothed cappuccino in front of Cranked, “I’d walk around nude if I wouldn’t get arrested.” He even went through a phase where he almost exclusively wore a kurta, the flowy, collarless shirt that is common among Indian men because it was the closest thing to being nude he could find.

But it wasn’t until he retired about a decade ago that my dad discovered the nudist lifestyle, after a friend invited him to a Can-Am volleyball tournament in Pennsylvania. There was a lot of jiggling involved.

“It was strange at first,” he says in the understatement of this young century. “When you’d get a point, the guys would hug. You’re all wet and sweaty. There were six players so I was in the back-middle, and you got guys in front of you with everything wagging and ‘a-dragging. But you get over it.”

A year later, on a visit to a nudist resort in Florida (I mean, where else?), he started to really get into the lifestyle.

“I just got over the staring, and I didn’t quite know that you’re supposed to stare at the eyes,” he says, hilariously. “But after a while, it just became natural. You don’t even realize you don’t have clothes on.”

He stresses that it has nothing to do with sex. Far from it. For some, he surmises that it represents a certain liberation, taking ownership of what God gave you and being proud of it. And, you know what? My 15-year-old self might cringe at this, but I think it’s pretty badass to be so comfortable in your own skin.

It’s funny though: he doesn’t think of himself as a nudist, in spite of his utter disdain for wearing clothes. There are times, for example, when he actually prefers wearing clothes, like when he’s playing pool or something called cornhole that I don’t care to look into further. Apparently, there’s a certain hierarchy in the nudist subculture, and being that my dad has only been to “maybe five nudist parks in my whole life,” he doesn’t consider himself a hardcore naturist.

“Sometimes I would just rather have a pair of shorts on,” he says. “But I do like not wearing clothes. That’s as simple as I can put it.”

I think that might make you a nudist, Dad.