Millions of TV viewers around the world watched as Jon Montgomery took his jubilant, victory stroll, beer pitcher in hand, through Whistler Village.

For many locals it was —and still is— an Olympic memory to top them all.

After all, the skeleton gold medallist's spontaneous celebration encompassed many of the elements that make up the building blocks of Whistler's DNA: Snow, sport, partying and a cheeky nod to the blue-collar crowd.

Today, as the fourth anniversary of Whistler 2010 approaches, and the Winter Olympics is set to open in Sochi, Russia, it's worth looking beyond the "Montgomery Moment" and asking, "What did Whistler really gain by way of Olympic legacies?"

Much has been made of the bloated price-tag that accompanies any Olympics but, if you take Sochi's $50-billion tab as the new benchmark in profligate spending, the Vancouver and Whistler Games' seems frugal by comparison, coming in at around $3 billion.

Even original Olympic skeptics like former Mayor Ken Melamed and current Mayor Nancy Wilhelm-Morden, have trouble finding much of a downside to hosting the Games.

In fact, says Melamed, three legacy items that have little to do with high-priced venues started paying back several years before the 2010 Games even started.

The first was an agreement with the B.C. government to allow Whistler to expand its boundaries by roughly 25,000 acres.

"This has allowed Whistler to control its destiny and exercise the commitments made in the official community plan," he told Pique recently. "It allowed significant expansion north and south."

Second, was the 300-acre plot of land near the then landfill, which was home to the athletes' village and now the high performance sports centre and the Cheakamus Crossing neighbourhoods.

"We only used about 75 acres for the athlete's village, so there's still a tremendous reserve there that the community can draw down over the years," says Melamed.

Last, but certainly not least, was the Resort Municipality Initiative funding program, or RMI, the grandiose title for the transfer of a portion of the hotel taxes into municipal coffers.

"It works out at about $7.5 million a year," he says. "We signed an agreement in 2006, so we're up about $49 million in additional revenues."

Melamed says the extra cash allowed Whistler to fund the Games, close the funding gap for the athletes' village and find additional cash for transit. As well, it provided a contingency fund going into the Games, helping Whistler contribute one third towards Whistler Olympic Plaza, the heart of Games' celebrations in 2010.

"Now, it's the gift that keeps on giving," he adds.

Melamed's perspective on the Olympics is that of a convert because, he says, he went into the Games highly skeptical and uninformed.

"Lots of people focus on the headlines about all the money that's involved," he added. "My epiphany was that there's a lot more than simply money, marketing and high profile sponsors. Whistler went into the Games with a whole pile of skepticism and went about putting in protection for the community, so we would emerge through this not just unscathed, but with something to show for it."

Canada's Games history has a checkered past. Remember Montreal with its debt-laden "Big Owe" Olympic Stadium? Built for the 1976 Summer Games, it took until 2006 to pay off the $1.5-billion debt.

"We went in under the pall of two notable, bad legacies," says Melamed. "Montreal had only just been paid off, and there was the fact that Canada had never won a gold medal as a host country."

Whistler's municipal Games-related budget started at $9.5 million and came in about $3 million under.

"In terms of economic legacies, we ended up roughly $1 billion to the good, if you want to tack in the highway improvements and all the money spent in and around Whistler," he adds. "That's an unbelievable return on investment for the community."

Mind you, two of those high-priced venues ended up costing a whopping $227.5 million.

Whistler Olympic Park came in at $122.5 million and the Whistler Sliding Centre cost $109 million. Both legacies, along with the Whistler Athletes' Centre are run by Whistler Sport Legacies.

"We always knew that the Olympics has a history of white elephants — these amazingly expensive venues," adds Melamed. "This is the part where you have to hold your nose. You know you have to have them, so you do the best you can."

It's tough, he says, to wrap your mind around the amount of money spent on venues for sports that involve very few athletes in the world.

"The sliding centre seems to be doing OK," he says, "Every year the Whistler Sport Legacies seems to be losing less money. But how many tracks does this sport need? There's 15 or 16 of them in the world now, I think."

The latest available figures show that in the year ending Mar. 31, 2013, the sliding centre took in about $837,000 in revenue, but cost $2.18 million to run — for a deficit of about $1.35 million.

Then there's Whistler Olympic Park, which took in close to $1.4 million, but cost more than $2.1 million — for a deficit of close to $775,000.

At the Callaghan Valley venue, the $30-million ski jumps sit largely unused, though last week the venue was designated a national training centre offering hope for a brighter future.

Though Melamed remains skeptical: "What to do with them?

"We went to Lillehammer, and if a Scandinavian country, the birthplace of ski jumping, can't make a go of it, how can we?"

The original plan was for the ski jumps to be a temporary installation, but it costs about as much to dismantle and move them, as it did to build them, says Melamed.

The cross-country trails at Whistler Olympic Park are being used for training programs and the Nordic Centre is popular in the Sea to Sky corridor, particularly for people from Squamish.

"It continues to be dogged by the fact that it's 30 minutes south of the village and to get a viable public transit system is going to take more work," he said. "That's its biggest challenge."

One thing you can't put a price on is national pride, says the ex-mayor, who admits he often had tears in his eyes during the Games.

"One person came up to me in the Village with a quote I'll never forget," says Melamed. "He said, 'We taught our children the words to O Canada but, during these Olympics, we've given them a reason to sing it.' I remember sitting in the stands at a ski event and behind me a row of high school kids just kept singing O Canada."

Melamed says he's disappointed in the way that Whistler, in the wake of so much euphoria, has now relegated the Games to the history books.

"One of the biggest let-downs for me is that it's almost become uncool to talk about the Olympics now," he says. "I don't get the sense that it's left a lingering glow in the village. That's a disappointment to me."

On the flip side, the $13-million Whistler Olympic Plaza is "one of the great joys and vindications" for Melamed.

"We got raked over the coals by many members of the community over that," he says. "There were people that said, 'Save the trees.' There were people that said, 'We have to have a multi-purpose arena on that site and nothing else will do.' Eventually we set upon what exists today."

The plaza has rounded out the village, says Melamed, giving it a central focus that was missing.

"It's proved successful beyond our expectations," he adds. "The village was missing that kind of central gathering place, flexible enough to be a great hang-out space for families to picnic and sit on the lawn, then to be heavily programmed into sporting event venues or concerts, with an accessible playground and icons that celebrate the Games."

He said the fact that the Audain Foundation for the Visual Arts has decided to invest millions to build the Audain Art Museum is a by product of the success of the plaza.

But Melamed says that as far as he's concerned, the undisputed jewel in the legacy crown is Cheakamus Crossing, the neighbourhood that grew from the $145-million athletes' village complex.

It takes a village

The Cheakamus Crossing neighbourhood includes 221 affordable ownership units, 55 affordable rental units, 188 youth hostel beds and 20 market-priced townhomes, as well as the high-performance athletes' training centre.

"The athletes' village dealt with the perennial backlog for housing in Whistler," says Melamed. "Some people had been waiting for eight years to purchase their stake in Whistler. They moved into the athletes' village and that freed up accommodation in rental housing market."

Eric Martin, president of the Whistler2020 Development Corp (WDC), was involved in the project from the pre-bid days of 2003, when he was vice-president of Bosa Development Corporation.

"Back in that time, the best bet would have been some kind of temporary village, with ATCO trailers or modular housing, that could be removed after the Olympics," he explains. "Our challenge was saying, 'Is there any way of creating a new community that would house Olympic athletes and provide housing afterwards?'"

Martin says there are still a handful of parcels of land that are fully developed and ready to be built on.

"We didn't need to build on them to satisfy our Olympic complement or the resident housing demand," he says, "There are six or seven fully-developed housing parcels ready to go, one of which we have already sold and which will be started next year."

Martin says that the whole Cheakamus Crossing neighborhood is between 65 and 75 acres and only between 30 and 35 acres have been developed so far.

Beyond that, there are another 100 acres of land, which are serviced to the boundary along the Cheakamus River.

To develop the whole area would require a plan stretching anything from 10 to 40 years, he says.

The original Cheakamus Crossing lands could support another 75 to 100 units with another 150 units in the remaining 35 acres.

Along the river, due to setback needs and environmental issues, a further 150 to 200 units could be built, he adds.

On the financial end, says Martin, WDC paid off $100 million in provincial debt by the end of 2012 and has started paying down the municipal debt.

"We still have $16 million owing to the municipality and last year we paid off about $2.2 million," he says adding that he's been involved in building between 20,000 and 30,000 units during his career with Bosa, and the Athletes' Village was a really small piece by comparison.

"But when I drive in there I take great pride in what I see," says Martin, who heads WDC for $1 a year. "I think the execution of what we set out to do was very well done."

The sport legacies

The deficit between revenues and expenses has been gradually shrinking, when it comes to operating Whistler Olympic Park and the Whistler Sliding Centre.

In its first full fiscal year, the two venues plus the Whistler Athletes' Centre, an accommodation lodge and high-performance training centre in Cheakamus Crossing, were in the red to the tune of over $5 million.

By March, 2013, that funding gap was down to $3.6 million, which was made up by funds from the Games Operating Trust. The trust pays roughly $2.7 million annually, with the rest coming from a B.C. government "transition grant." The government has guaranteed it will pay $2.7 million over three years until March 2015.

According to Roger Soane, president and CEO of Whistler Sport Legacies, two things may have a negative impact on income for 2013-14.

Because of a bad snow year, November and December were slower than anticipated at Whistler Olympic Park.

At the Sliding Centre, while programs for the public are "doing exceedingly well," because it's an Olympic year, some of the national teams went to Sochi to train, and so the track wasn't used as much by them as in past years.

"We average about 100 slides a day throughout the season, whether it be sport or public use, and our season starts in October and runs through until the end of March," said Soane. "We're going to keep that pace (though) it's going to be made up of local clubs, provincial and more second-tier users, rather than the national team."

Homegrown talent like junior lugers Jenna Spencer and Reid Watts had never tried the sport until the Olympic venue was built in Whistler.

"In four years they will have become the future of the sport," says Soane. "When you put in the dollar amount you say, 'Wow, isn't it an expensive operation?' It is, but I don't think there are many sporting complexes or facilities that are built to make a profit, whether it is the local recreation centre or the swimming pool. They all cost money."

Watts, 15, has been away in Europe recently, training with the Canadian junior team.

"He got his start on the Whistler track when he was nine, on the development team, before the Olympics," said dad, Jim Watts, president of Whistler Parking Management. "He just liked watching the sleds at the track and we heard there were recruitment camps. He went to one of those and, after his first run, he was hooked."

One Olympic legacy that doesn't get enough recognition is the continuing promotion that televised World Cup competitions bring to Whistler, he adds.

"We tend to have one or two World Cups every year on that track and you're bringing 20-plus countries with their teams and they're staying here for usually a few weeks and they're all staying in hotels and being catered to," says Watts. "That alone is a big economic boom, but you also have the HD TV trucks here for these events and in Europe you have millions of people watching."

Soaring into the future

As far as the ski jumps go, Soane says the Canadian Olympic team will have used them twice this season, most recently in the build-up to Sochi.

"I think they'll be used four times this season for a total of 20 to 30 days," he said.

WSL has approval to build a new 20-metre and a 40-metre jump, costing about $200,000, so that a junior training program can be launched.

"Canada has a relatively strong woman's team, we're looking to use that as a springboard and take the DNA from the youth in Whistler to see if we can start a junior program in the Sea to Sky corridor," Soane adds. "Because we only had two Olympic jumps, it wasn't designed to train at the introductory level. So we are building a couple of jumps so we can start an introductory program for juniors."

The money will come out of the Games Operating Trust.

Soane says that whereas other former Olympic ski jumps operate summer attractions, often involving zip-lines, WSL is reluctant to do anything that would compete with private sector companies in the Sea to Sky corridor.

"This year we're introducing a new thing at Whistler Olympic Park called the Bromley Board," says Soane. "It's a snow skeleton, a bit like a toboggan, developed by an Olympic athlete called Kris Bromley in the U.K. It's used on snow as an alterative to going down the track."

A new 500-metre run has been developed at WOP and the Bromley boards will be used for a test season.

"If it works out we'll put a tow in," he adds. "Right now we're using a snowmobile to transport people up and down. You'll rent a board for an hour and you can do as many runs as you want."

At the sliding centre, a wheeled, summer bobsleigh will be introduced in July, purely as a tourist attraction.

Asked whether building housing would be considered as a way to raise operating capital a WOP, Soane says that was something that was part of original planning.

"We have brushed over it and looked at it, but it's not a model we're thinking of moving forward on yet," he says. "If we did anything, it would be camping or RV parking, so that in the summer months people could use the facility and use the area for hiking and biking and things like that. Right now tourist accommodation is well-catered for in Whistler."

If there was to be any plan for winter accommodation at WOP, it would be something "completely unique and different" such as a cabin development, adds Soane.

"We've looked at that, but right now our mandate is more about sport than it is to develop the land out there," he says. "It would be a source of income, but the land that was given to us has a lot of other interests there, like the First Nations' interests, so it's not in the near future."

Partnerships

Brad Sills, president of Callaghan Country Wilderness Adventures says that the transition team faced a huge task when it converted Whistler Olympic Park from a Games-related facility into a recreational complex.

"They looked at the Nordic Centre and realized that their success, in fact their very survivability, was going to be based on creating the biggest, best Nordic experience in North America," says Sills.

The result was a partnership called Ski Callaghan, which is the amalgamation of the Nordic cross-country complex and Callaghan Country, which is more of a backcountry operation, with 42 kilometres of groomed trails.

The two enterprises operate as independent businesses, but unite under a common banner for marketing purposes, and a single-gate admission gets you into both properties.

"We like to say, 'we put the cross-country back into cross-country skiing,'" chuckles Sills. "We're destination-oriented and we operate a 24-person, overnight, full-service lodge that is 13.5 kilometres from our base. So what we bring to the table is a wilderness experience to the Nordic market, as well as a series of more intimate, back-country snowshoe opportunities."

The lodge is open for lunch, and is a three-and-a-half-hour ski in for a rank beginner and about an hour for a keen skinny-ski skier.

"More people are discovering that you can actually travel places with the skills that you've honed at Olympic Park," says Sills. "It opens up the market. In North America we tend to go around in circles and Nordic skiing tends to be an athletic pursuit whereas, when you go to Europe, it's not like that at all. There, you tend to go from village to village and it's much more social."

Last year, the two facilities increased overall ticket sales by close to 20 per cent and were on track to do that again this year through season ticket sales until the weather didn't co-operate.

Last year they had 42,000 visits, says Sills, of which Callaghan Country accounts for 15 to 20 per cent.

If the Olympics hadn't come to Whistler, Callaghan Country would have been operating, but without an improved highway to the doorstep and electricity.

While some people argue that the $800-million in Sea to Sky Highway upgrades would have happened eventually anyway, Sills says it's an "extraordinary" legacy of the Games that some people take for granted.

"I had a number of friends that perished on that highway and a number more who were seriously injured," he says. "The rate of accidents has dropped dramatically and it's actually pleasant coming back from Vancouver on a rainy night. You don't get home gripped in fear and have to drink four Scotches."

The Olympics, he says, supplied huge benefits to his company.

"The biggest one was that it raised the profile of Nordic skiing in the Sea to Sky corridor immensely, to where we can now compete in the North American market for destination visitors," says Sills. "That's our next task, to start developing that market."

From the mayor's chair

When it comes to Olympic legacies, Mayor Nancy Wilhelm-Morden agrees that Cheakamus Crossing is by far the best one.

"It was transformed into an affordable housing neighbourhood," she told Pique. "It's now home to 880 residents and I understand there's a mini baby-boom going on down there, so that's in my opinion, by far and away, the best legacy."

Wilhelm-Morden has lived in Whistler for 40 years and, while she was not originally an Olympic supporter, her family stayed in town for the Games and hosted friends and family.

"I was so proud of Whistler and what a magnificent job it did in being the mountain host," she says.

An important by product of hosting is a whole new focus on "cultural tourism" which has grown out of programming at the live sites during the Games.

"There was a realization that we can do this outside the Games period," she says. "So we've kept on with our cultural tourism initiative and I'm really excited about that."

That has resulted in expanded festivals and events at Whistler Olympic Plaza, including the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra coming for expanded stays.

"We've got the Audain Art Museum, which is going to be a fabulous facility when it's completed in 2015," she says. "We've just got our cultural plan and it's got 30 recommendations on how local, home-grown cultural activities can be expanded, so we're really moving into a new and exciting era for Whistler."

She disagrees with Melamed that Whistler isn't still embracing the Olympic spirit.

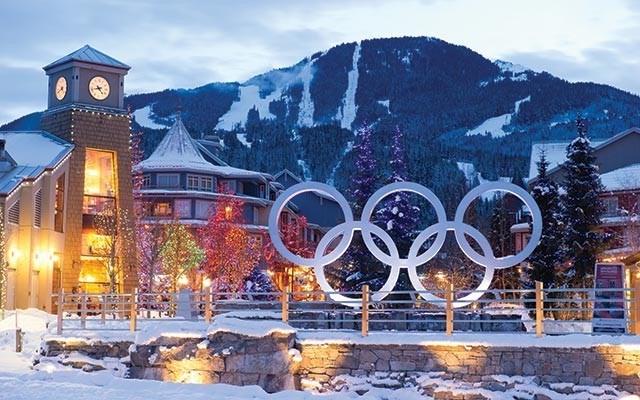

"All you have to do is go to Whistler Olympic Plaza and look at the Olympic rings and the Paralympic agitos, that are very prominently displayed, and the First Nations welcoming figures. You can't stand by the rings at any time of the day and night and not see people having their photographs taken in front of them. There is still definitely an Olympic buzz in Whistler."

Wilhelm-Morden has many fond memories of the Games in Whistler.

"It was 16 days of excitement, whether we were in the village in the evening when the medals were presented, or when we went up Whistler Mountain several times to watch the events," she added. "Just the feel of it was quite remarkable. We were in the village when Montgomery went through with his big pitcher of beer. There are so many memories."

She said she'd like to see the International Olympic Committee cut back the amount of money that's being spent on the Games.

"I don't know if it's necessary to go into these places and build these same facilities, all over again, every four years. Frankly it seems wasteful," she said.

Would she like to see the Games come back if the opportunity arose?

"I think we've had them once, that's enough."

Taking PRIDE

One legacy of the Games, which was celebrated at WinterPRIDE last week, was being the first mountain host to have an Olympic Pride House.

It was one of three, officially sanctioned, gay-friendly venues; one in Whistler and two in Vancouver and activists are travelling to Sochi to try to persuade organizers there to do the same.

Even if those efforts prove unsuccessful, Whistler and Vancouver's groundbreaking move sparked a Pride House in London at the 2012 Summer Games. And there will be similar pavilions at the 2014 FIFA World Cup in Rio de Janeiro, at the 2015 Pan Am Games in Toronto and at the 2016 Summer Games in Brazil, says Maureen Douglas.

Douglas is in Sochi this week with Vancouver city councillor Tim Stevenson as part of a delegation seeking to entrench host city pride houses and the inclusion in the Olympic Charter of guarantees to protect sexual orientation.

Douglas spent eight years as director of community relations and communications for Vancouver Organizing Committee for the 2010 Games.

"In Whistler we like to think we welcome the world and we do," says Douglas. "But the Olympic Games is the only place where I've seen the concept of the global village come to life."

One of the biggest intangible legacies left by the Games is the knowledge that Whistler can take on the biggest events, she says.

"It leaves you with an ability to aspire higher and actually achieve it."

Though she adds, "sometimes it's not the blessing you think it is. It's set the bar very high. Our Olympic lesson was that, as a group, you can achieve a phenomenal amount more with a little bit more energy. That's the kind of knowledge we don't want to let go of."

Dean Nelson, who spearheaded Pride House, said the pavilions in Whistler and Vancouver became the third most talked about story of the 2010 Olympics.

"Before 2010, the conversation about gays and sport, especially at the Olympic level, had never been vocalized," he said. "Some of the senior leadership within the sporting organizations felt more comfortable after 2010, because the world didn't come crashing down. You didn't have major protests. It became normal and that's all we're asking for — to be treated with equal respect and dignity."

The last word

Robert VanWynsberghe, an assistant professor at UBC's department of educational studies, says the key legacy question may revolve around who's going to keep paying to keep the money-burning venues running.

"At some point, is it all going to fall on the municipality, if they want to keep those things going?" he asks.

He said it's things like Cheakamus Crossing that are the true benefits.

"They've virtually built a suburb," he adds. "They got $50 million from the province and the feds (towards the athletes' village). That's free money and you don't get that unless you're hosting the Games."

Overall, it's good to be a host city, says VanWynsberghe, who's currently writing a paper using 2010 data on how host cities can leverage mega sports events.

"Mind you, I couldn't think of two places that needed to host the Games any less than Vancouver or Whistler. They're already inundated with tourists."