Murray Sovereign, owner of Valhalla Pure Sports in Squamish, knows how rare it is to come across another telemark skier in 2021.

“I’m not sure I have spent a single day at [Whistler Blackcomb] skiing with another telemarker in the 22 years I’ve been here. I see them in the lift line and watch the odd one go by while I’m riding the chair, but it’s such a large ski area, and there are so few of us there on any given day, it’s a bit like two sailboats out on the Pacific Ocean; the odds are against them catching sight of one another.”

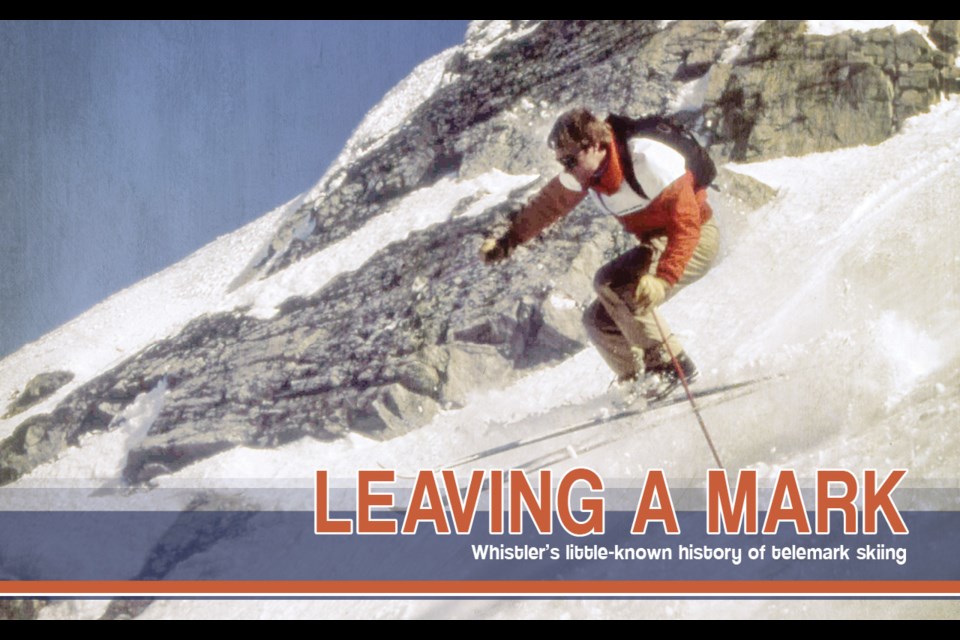

Had Sovereign arrived here in 1982, he would have witnessed a very different scene. Although there were probably fewer than 300 telemark skiers on both mountains combined on a busy day, it was a sport, which combines elements of alpine and Nordic, that punched well above its weight, especially in mountain town newspapers and magazines. Downhill skiers would often watch in awe as telemarkers submerged themselves in the depths of Coast Range powder.

“For me, it all started in 1980 when I was loading the Blue Chair and watched the bartender from the Boot tele down Chunky’s on a powder day. And I thought to myself, this is a cool thing,” says Whistler environmental consultant and telemarker David Williamson.

Indeed it was, and Whistler town councillor and retired ski patroller Cathy Jewett is the first to admit it. “It sounds pretty lame but I guess I started telemarking because all the cool kids were doing it,” she says.

For many skiers—alpine and cross-country fanatics, especially—telemarking proved to be the perfect vehicle for exploring the glorious Coast backcountry. Lightweight skis, boots and bindings—almost a third lighter than the current crop of alpine touring gear—offered the opportunity for quick missions into the Whistler backcountry, which was a lot closer to town and not as widely lift-serviced as it is now. “We didn’t really need climbing skins back then; there were bootpacks to the most popular bowls,” Jewett says.

Then there were those restless young men and women who washed up at Whistler in the early 1980s and were simply bored with downhill skiing—especially the ones who’d spent their teens slavishly devoted to ski racing. They wanted to try something new, and ironically what they got was a ski trip through memory lane courtesy of a Norwegian skier named Sondre Norheim and a handful of American hippies.

Where downhill and cross country meet

Telemark skiing in the late 20th century was a meeting place between downhill skiing—which originated in the Alpine countries of Switzerland, Austria, France and Italy—and cross-country skiing as practiced in the somewhat flatter Nordic nations of Norway, Sweden, Finland and many parts of Russia. It was first developed in the 19th century by Norwegian ski jumper Sondre Norheim as a method of stabilizing his landings by kneeling and extending his front ski while staying balanced on the rear ski. By the 1860s, Norheim was one of the top ski jumpers in the world and his landing style soon became the standard for ski jumpers everywhere. In fact, it’s still in use today.

The telemark position has been compared to Catholic pilgrims bowing on bended knee, and indeed some believe telemarking in boot-top powder can be a religious experience. The key to this flow state lies in mastering the lunging motion that marks the transition from one turn to the next. It’s a move that requires balance, grace, power, coordination and, more than anything, an intuitive feel for the snow.

Unlike their alpine brethren, Nordic jumping and cross-country skis are pretty much straight from tip to tail, meaning that they have next to no sidecut or shape. A lightweight pair of cross-country skis is literally impossible to turn unless you throw your entire body sideways, although as we know, skiers like Donnie Campbell, one of Whistler’s early telemarkers, can make magic out of pretty much anything on their feet.

Quite improbably, the rebirth of this elegant turn would take place tens of thousands of kilometres from Norheim’s telemark birthplace, at a small but mighty mountain in southwestern Colorado. A ski instructor at Crested Butte named Ric Borkovec is widely-regarded as the sport’s Messiah, spreading the gospel to the rest of western North America. When Campbell and Binmore drove to Crested Butte to compete in the North American Championships in the early ‘80s, they were astounded at the number—and seriousness—of the racers in attendance. Telemarking, initially derided as some granola-eating hippie sport, was growing up.

Grandpa Telemark

Campbell is a wiry 67-year-old affectionately known as the Sea to Sky’s “Grandpa Telemark” largely because he’s one of very few ‘80s-era skiers who never converted to alpine touring. Campbell still has the wooden Bonna skis that he first learned to cross-country ski on at Manning Park; the ones with the screw-in edges and Villom three-pin binding. “The first time I saw anyone telemark was in the late ‘70s. My brother and I were staying in a hut down near Mount Baker and this mountain guide took us out and showed us how it was done—in three feet of fresh powder.”

Campbell’s gear—and the places he’s been with it—has evolved a lot since that time. “Last year, I had Johnny “Foon” [Chilton] make me a pair of custom skis and those cost $1,500. The Design 22 bindings cost $700, but I still use a pair of Scarpa TWXs that are a few years old,” he says. As of March 13, Campbell’s racked up 53 days for the season, including a stretch of nine in a row.

Campbell’s either found the secret fountain of youth or maybe it’s all of that organic Pemberton produce. More than anything, it’s likely that practice makes perfect—and like Malcolm Gladwell’s 10,000-hour rule, he’s honed his technique since taking his first lessons from Jamie Sproul at Forbidden Plateau in the early ‘80s. Moving to Whistler in the spring of 1984, Campbell became a fixture on the local racing scene as well as Whistler Mountain’s first telemarking instructor. (A second instructor, Lori-Anne Speed, was added the following year).

The Whistler Connection

Seeking a career in the ski industry, Whistler’s Wayne Binmore travelled to the United States and enrolled in the Colorado Mountain College in the high-altitude town of Leadville. He saw telemarkers on the slopes of Summit County near Breckenridge, picked up some gear and started fooling around with it at Ski Cooper. “It was a flat hill with slow lifts; perfect for learning,” he says.

There were no instructional videos at the time, though most mountain town bookstores carried Steve Barnett’s Cross Country Downhill (Pacific Search Press, 1976). Filled with classic photos of hippie dudes aggressively attacking manky snow conditions on super-lightweight gear, Cross Country Downhill became a seminal text. Barnett, who lived over in the Methow Valley in eastern Washington, even attended one of Whistler’s telemark races in 1985.

The hippie part is worth mentioning, because as the sport gained followers in Whistler and elsewhere, there were many early adherents whose interest in telemarking was as a tool for exploring the backcountry. In Utah and Colorado, telemarkers are seen as the original dirtbags; far closer in personal hygiene and spending habits to the climbers and mountaineers inhabiting Yosemite, the High Sierra, and the San Juans. The idea of spending money on a day pass was anathema to their very lifestyle. Even in Whistler, the combo of climbing skins and light gear—along with a lift policy that only checked day tickets at the base of each mountain—led to a secret outlaw culture of poaching lines without paying for a ticket.

There was a vexing contradiction to telemarking, however, that even skilled alpine skiers had to deal with. It was brutally difficult to learn, and most of the knowledge was passed along by skiers who might only have a few days’ more experience than you did.

“I’m pretty sure I mostly taught myself. The first few weeks were incredibly humbling,” says telemarker and mountain guide Ramin Sherkat. “I was just getting hammered on green-dot runs after years of skiing double blacks on downhill gear.” Though he converted to lightweight alpine touring gear many years ago, telemarking proved to be a valuable waypoint on his way to becoming a certified Canadian mountain guide.

Telemarkers needed a support network. And looking back, it’s ironic that telemark racing would become the glue that held the sport together.

The racing circuit

By the mid ‘80s, enthusiasm was high but access to gear still lagged. Traditional specialty downhill ski shops wanted nothing to do with tele skis, Mountain Equipment Co-op was slow to respond and their product selection was oriented to softer flexing backcountry gear.

It was left to scrappy Coast Mountain Sports, a flashy new specialty store on West Fourth Avenue, to take up the telemarking flame and run with it. Owner Randy Hooper went all-in, creating a B.C.-wide telemark racing series, with events at Tod Mountain in Kamloops, Apex Resort in Penticton, Mount Washington on Vancouver Island and Red Mountain near Rossland. Jewett even remembers driving down from Whistler to compete in night events at Cypress and Grouse.

“We’d have races over at Red and all of these hippies would come up from Montana and Idaho. They styled the baggy wool knickers and pointy (and itchy) brown alpaca wool hats that one writer christened the ‘telemark helmet,’” recalled former racer Wayne Binmore. “They really added a lot to the vibe.”

It was all fun and games for the “pinheads,”as they became known. Races often ended by all of the participants linking arms and attempting to telemark in sync, a manoeuvre that might last for a few turns before the human chain fell apart.

Not every town rolled out the welcome mat, though. “A couple of friends and I were sponsored by Karhu in the beginning,” Binmore says. “We went up for an event at Tod Mountain and were booked at a place in downtown Kamloops. We dropped a bunch of skis in the lobby and went up to check our rooms and when we got back, half a dozen pairs of skis were gone. It was bizarre because there were staff persons at the front desk the whole time.” Thanks to Karhu’s generosity, Binmore and co. were able to successfully compete in the races.

There is, of course, a tendency to view this mid-‘80s period through rose-coloured glasses, and maybe even a haze of B.C. bud. (Jewett recalls being billeted at the Canadian Championships in Fernie. “The spare bedroom had all of these bright lights and green plants everywhere. We were told to sleep on the couch.”)

Binmore raced in three North American championships, all of them in Colorado—where the sport’s Second Coming had arrived in woodsy, counterculture towns like Breckenridge, Telluride and, most notably, Crested Butte. “You would find quite a few [ex-U.S. ski team] and college racers at these events. Dropouts who had become bored by alpine skiing but who also wanted the speed and performance they were used to from alpine racing,” he says.

Hence, Asolo Extreme or Merrell Comp boots would be stiffened by all sorts of hacks to increase edge control. The old-fashioned “Jet Stix” that freestyle skiers used to shore up the back of their plastic downhill boots were pressed into service to prevent getting in the “backseat.”

One prized piece of gear was what became known as “the Frankenboot.” “We’d scour garage sales, ski shops and our parents’ basements looking for those rock-hard, old-leather downhill boots that had been replaced by plastic boots such as Langes,” Binmore says. “Of course, those boots were made for ‘parallel’ skiing, so we would take these boots to a cobbler over on Commercial Drive and he’d manually sew on a three-pin duckbill Vibram sole to work with the popular bindings at the time.”

Campbell’s hack was even more outrageous. “We would cut the entire toe area out from a downhill boot and stuff a telemark boot through it. This allowed the Vibram sole of the telemark boot to flex freely under the ball of the foot, while providing enormous power transmission to the edges by allowing the ankles and knees and hips to roll as one unit,” he says.

By the time that Binmore competed in his final international race, “I was now on Kazamas, a Japanese ski company that had been around at the very beginning. The brand was really trying to focus on racing, and they supplied me with a speed suit and these ridiculously stiff skis with five holes drilled through the tips. The skis were fine on the course, but you couldn’t go anywhere near powder or tight trees with ‘em.”

The last major event held at Whistler was the Telemark World Championships in 1996, which, as its title implies, hosted athletes from all over the world. There had been many changes in the previous decade: While there was still head-to-head racing, competitors had to enter the incredibly daunting event known as “Classic Telemark,” where skiers must first flash around a series of gates, fly off a gelandesprung-style jump—and land perfectly in the telemark position, herringbone uphill for several hundred metres, ski back through more gates and, for the grand finale, complete the reipelokke—“the banked circle”—where each skier has to skate 360 degrees before crossing the finish line. Unlike timed or head-to-head giant slalom races, these competitions push racers to lung-busting exhaustion in times lasting from five to seven minutes long. Classic Telemark was invented to ensure that ex-alpine racers would not dominate events due to their superior technical ability.

Sounds like fun, eh? Well, it’s worth noting that the Masters champion in this event held 25 years ago was none other than Donnie Campbell. And you wouldn’t bet against Grandpa Telemark again.

There were many locals who contributed to the telemark scene over the years that unfortunately didn’t make it into this piece, so a shoutout goes to some of the other members of the Whistler telemark tribe: the Jette brothers (Pierre and Andre); Jean-Louis Arsenault; Sue Boyd; Paul “Finn” Saarinen; John Townley; Andy Hoppenrath; Mary McDonagh; Dave Patterson; Rumi Merali; Wendy Ladner-Beaudry; and former Pique scribe Michel Beaudry.