Nunavut is Canada’s newest territory, Prime Minister Jean Chretien is still months away from getting pied in the face, boy bands dominate the music charts, and, in a low for fashion history, frosted tips and puka-shell necklaces are all the rage.

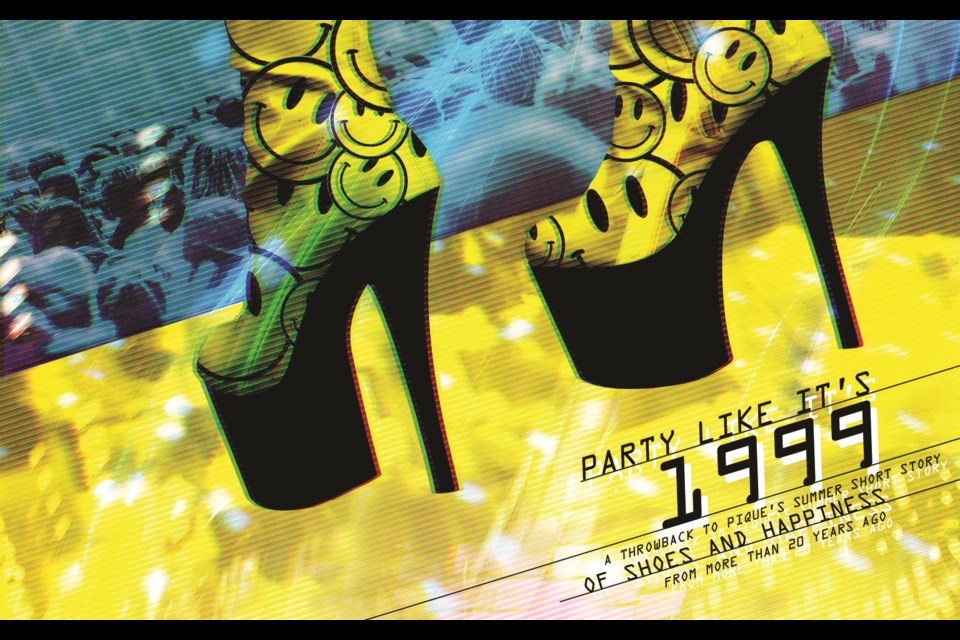

It’s 1999, the last days of the millennium (hey, remember all that Y2K hullabaloo?), and in Whistler, Pique Newsmagazine is a fresh-faced five years old, still finding its legs as the resort’s irreverent, independent weekly.

In the dog days of summer, typically a slow period news-wise, Pique launched a summer short story contest open to any and all writers who were inclined. Twenty-three-year-old Kiwi Kara-Leah Grant heeded the call, and her whimsical winning entry, “Of Shoes and Happiness” took home the top prize, despite being wildly over the word limit.

“I remember being at dinner with G.D. Maxwell, who writes the column on the back page, and he told me, ‘You know your story was way over, right? But it was also way better than anything else submitted so we had to run it,’” Grant recalls, today a yoga teacher and author of three non-fiction books, including Sex, Drugs & (mostly) Yoga, which recounts some of her time in Whistler.

Maybe it’s because we’re feeling a tad nostalgic these days (I mean, who isn’t?), Pique went back to the archives to revisit Grant’s winning tale, which we hope helps get you through your own dog days of summer. And stay tuned for a short Q&A with the author following the story.

- Brandon Barrett

Once upon a time, in a country not too different to this one, there was a village.

The village, Shortsbury, was much like any other small village. There was the general store, which had been in Mrs. Brown’s family for generations and sold everything from licorice and string to pots and flour. There was a tiny school, a rather old church and a fabric store that sometimes doubled as a blacksmith.

People in Shortsbury had lived there all their lives and the few who did leave never ever came back.

Life in Shortsbury was very pleasant, the sun shone most days, there were plenty of fish in the local river and the town jail hadn’t been used since Mrs. Brown’s grandfather ran the store.

Fifteen miles up river was another village very much like Shortsbury. Except, the sun seemed to shine a bit more often there, the fish practically jumped on to a fishing line and they didn’t even have a town jail.

Oh, and they were tall. Compared to Shortsburians anyway. For some long forgotten reason, people born in Shortsbury were short. Not dwarf-short, just never more than 5-6. That would have been OK except for that village 15 miles up river. Talleston, it was called. Not that the people there were particularly tall, just 5-10 or so on average. The problem was, Tallestoners couldn’t resist pointing out that their taller village always seemed to be a little better than the smaller Shortsbury. They always won the annual strongman and brightwoman contests, leaving second place to Shortsbury. Still, people in Shortsbury weren’t a complaining bunch and they felt they had a pretty good life.

One fine fall day, much like the other days that week, a stranger rode into town. Nobody took much notice and rode straight out the other side on their way to Talleston.

This stranger didn’t. She slowed her horse down outside the only pub in town, dismounted and strode in.

“A pint of your finest, please.”

Head turned, It was mid-afternoon and the locals were starting to drift in. The barman placed the pint in front of the woman, trying not to stare, but failing miserably. She ignored him and sat down. For a while nothing much happened. The locals continued to glance over at the stranger, she continued to ignore them. Then she finished her beer and stood up.

“Where’s the real estate office, please?”

Despite her commanding tone, her voice was quite musical and the bartender noted she was rather polite. For a stranger, that is.

“Er…”

For a moment, he couldn’t think. Did they even have a real estate office in Shortsbury?

“Straight up the road and on your left,” drawled one of the locals, his piercing blue eyes meeting hers.

“Thanks.”

She strode out. The locals shrugged and went back to their beers. Two days passed before the full story of the stranger was put together from different sources. She’d gone up to the real estate office and paid cash to rent a store in town, then she’d moved her rucksack into the rooms above and disappeared again, riding out the way she’d come in.

People talked about it for a few days. Nobody could remember what the store used to sell, it had gone out of business so long ago. What she wanted with it was a mystery. By the end of the week, the stranger was forgotten and people gossiped about other things.

One day in late fall the stranger rode back into town. This time her horse pulled a wagon and the woman spent the day unloading boxes into the store before disappearing again. The gossip only lasted a day this time. There wasn’t much you could say about boxes. What happened next, though…

Monday morning, Mrs. Brown was on her way to open the general store in time for her first customers at 9 a.m. She glanced over at the woman’s store. And stopped. Mrs. Brown stared at the sign, she read it slowly, then re-read it. For the first time in Shortsbury’s history, the general store opened three minutes late.

A lot of people walked past the woman’s store that day. They all read the sign, but none of them went in. At 6 p.m. on the dot, just as the sun was sinking below the hills, the woman turned the open sign to closed, locked the door and left for the pub.

The pub was full and louder than usual. Everyone had something to say and some of the arguments were getting rather heated.

“A pint of your finest, please.”

The pub hushed. Everybody looked. She sat down on a barstool and leaned casually against the wooden bartop. One might have suspected she was waiting for something but she just sat there and continued to drink beer.

“So what’s your sign?”

She glanced up and met the same piercing blue eyes that had given her directions to the real estate office.

“Nothing. It’s what I sell.”

She met his stare and didn’t move, taking a long gulp of her beer as he continued to watch her.

“Mmm…”

He signalled the bartender and ordered another two beers.

“My name’s Blue-Eyes. Johnny Blue-Eyes.”

She took the offered hand and shook it, the barest hint of a smile playing around her eyes.

“Catriona Sells.”

They drank their beers in silence, unaware the whole pub had been listening and watching their conversation.

“So,” Johnny broke the silence, “you sell shoes.”

“That’s right.”

“Shoes that make you taller.”

“Correct.”

“Shoes that make you taller without a visible heel.”

This time she smiled. “I see you’ve read my sign.”

“How?”

“Sorry?”

“How do they make you taller?”

“Ah, that’s a trade secret, I’m afraid. Why don’t you stop by the store tomorrow and try some on. After all, the proof is in the wearing.”

Catriona stood, thanked Johnny for the beer and strode out of the pub. The wagging tongues started well before the door even shut.

Her doors opened at 9 a.m. the next morning and at 9:12 Johnny strolled in.

“Black leather. Size 12.”

He sat down.

“Please.”

Catriona strode out the back of the store to find a 12, giving Johnny a chance to look around. It looked like any other shoe store. Men’s, women’s and children’s shoes each lined one wall and the window display was full of the latest fashion.

“Here you are.”

Johnny took the shoe and turned it over, glancing curiously at the sole.

“It’s just an ordinary shoe.”

Catriona smiled.

“No, it’s not. This one has a height increaser of two inches. Should make you about my height, 5-9.”

Johnny frowned and then slipped the shoe on.

“Fits.”

He laced the shoe and then put the other one on. Johnny slowly stood up and found himself at eye level with Catriona.

“Huh.” He took a step. “It feels… high.”

“Of course it does. You can’t gain two inches and expect to balance the same. Take a walk around the store.”

Johnny obeyed and was surprised to find that he actually felt a little wobbly. He stopped and peered down at the shoes.

“Don’t worry, you’ll get used to it very quickly.”

Catriona walked over to the till.

“Will that be cash?”

“Uh, yeah,” said Johnny, staring down at the shoes. He was out of the store and down the road before he realized he had just paid half a week’s wages for shoes that were supposed to make you taller.

“Catriona Sells,” he muttered, shaking his head. “She sure does.”

Things moved very quickly after that. Word got around and by late morning, Catriona was beginning to sell out of the more popular sizes.

“Sorry, sir,” she said to Mr. Bottom, the town mayor. “I sold my last size 9 at 10:30 a.m.”

“Oh,” the mayor frowned. He was a small man even for a Shortsburian, but the people still voted him in as mayor every year, just as they had done with his mother before him.

Catriona smiled. “Will next Tuesday be all right?”

“Next Tuesday?”

“That’s when my next shipment is due.”

“Oh, yes. Right.”

The mayor smiled, suddenly liking this stranger who had ridden into town one fine fall’s day.

“Tell you what, I’ll pay now, then I’ll be certain to get a pair.”

“Certainly, sir. Just let me get the paperwork.”

Shortsbury’s local police chief was out of town this particular day, attending one of the courses the city sporadically held for all the regional police chiefs. This one was on improving social relations with the public.

Police Chief Andrea Hardnose didn’t think it was that relevant to her, but forced herself to stay right to the end. After all, the local police chief must set an example.

It was nearly 8 p.m. when Hardnose made it to the pub for her nightly whiskey and ginger. She was tired and grumpy after the one-and-a-half-hour ride back from the city, and just grunted when the barman handed her the drink. A sip of her drink went some way towards improving her mood. Taking another sip she glanced around the dimly lit pub. Then frowned. She looked again. Something was not quite right. Chief Hardnose puzzled over it for a while but her brain was feeling decidedly dead, so she finished her drink and left.

Next morning dawned bright and clear, maybe a little brighter and a little clearer than normal. People said hello to each other in the street with a little more enthusiasm than normal. Even the birds seemed a little chirpier.

Business was again brisk at Sells’ Shoes and by lunchtime, Catriona was both pleased and exhausted. She’d almost sold out all her stock, so decided to close for the day.

She was just locking the front door when she spied Johnny down the street. Catriona waved and smiled as he walked back towards her.

“I see your balance has improved.”

Johnny grinned. “Sure has. These shoes are great. I feel like I’ve got a new lease on life.”

“Really?” Catriona pointed to the sign she’d just put in her window: “Closed until Tuesday, new stock arriving.”

“I’ll do a trade-in next week if you like,” she said.

“A trade-in?”

“I’m getting some three-inch stock in. I can do you a deal if you want to move up.”

She pocketed her keys. “Come and see me next week.”

Johnny stared at Catriona as she strode down the street to the pub.

“Three-inch heels?” He shook his head and continued down the street towards Mrs. Brown’s General Store.

“Morning, Johnny,” Mrs. Brown said as he pushed the door open.

“Morning.”

“Come for some cigarettes?”

“Yes ma’am.”

Johnny started counting the money out, even though he knew he had the exact change.

“You look different today, Johnny.”

“Do I?”

“Yes,” Mrs. Brown peered closely at him.

“You get a haircut?”

“No, ma’am.”

“Hmph. When are you going to find yourself a girl anyway? You must be nearly 25, my boy.”

Johnny handed her the coins.

“To the day, Mrs. Brown,” he grinned and turned to leave.

“You’re taller!” exclaimed Mrs. Brown as she suddenly clicked.

“Sorry?”

“What the hell have you done to yourself, Johnny? That there counter used to be at your stomach but now it’s closer to your hips.”

Mrs. Brown stared down at him. She was one of the few Shortburians to hit 5-10. It was rumoured her mother had once been with a Tallestoner, but Mrs. Brown was very tightlipped about it.

Johnny shifted uncomfortably in his shoes. He’d known Mrs. Brown since he was a boy. She reminded him a bit of a rather stern but kind school teacher.

“Um, new shoes, ma’am.”

“New shoes?” Mrs. Brown frowned again. “Seems to me a few people have new shoes in town.”

“Yes, ma’am. Shop just opened, that’s all.”

She stared hard at Johnny. “Them shoes make you taller, don’t they, boy? Now why would you want to be taller, huh? That’s what I want to know.”

Johnny said nothing, just glanced at his watch.

“That’s right, Johnny, your lunch break’s nearly over. You skedaddle out of here. Oh, and don’t break you ankle on the steps now, you hear?”

Tuesday rolled around and the mayor got his new shoes and grew three inches. For the first time ever he found he could glare down some of the councillors. Johnny came in and traded up to a three-inch heel.

Catriona continued to sell shoes. By Friday she was sold out again.

Saturday was officially the last day of fall, the day when Shortsbury held its annual fair. Traditionally, Talleston council hopped on a bus and Tallestoners came down to try their luck at the games. Like every year, their luck was very good; 100 per cent, in fact.

The atmosphere at the fair was very optimistic this year. Shortsbury’s local strong man, Ian Hearth, said he’d been lifting more than usual in the last week or so. Renee Goddit, the local brightwoman, was also feeling confident. She’d spent the last week memorizing the latest edition of The City Encyclopedia and found it surprisingly easy. Both were confident in a win.

History was against them, though. After all, Tallestoners had their 100-per-cent record behind them.

The Tallestoners bounded off the bus, every pore oozing confidence. It didn’t take them long to realize something was up.

“Shortsburians have grown!”

“Impossible. They’ve always been short.”

‘They have! Look, he’s my height.”

As the Tallestoners talked amongst themselves, their confidence began to seep away. It slowly emptied out of their pores as they faced a taller and more upbeat group of Shortsburians than any of them could ever imagine.

The strongman contest was first and Talleston’s representative didn’t feel quite as confident as the last five years, especially when he realized Ian Hearth was actually a little bit taller than him.

Twenty minutes later, Ian was ecstatic with his win and the Tallestoners seemed to melt into the background.

The brightwoman contest was next; it was no surprise to the crowd when Renee Goddit romped in.

The Talleston bus left before the prize-giving. Shortsburians muttered something about being sore losers, but were too excited to really care.

Shortsburians’ fortunes just seemed to keep improving that winter. The weather seemed better, more money poured into town, a record-sized fish was caught in the local river and even the people seemed happier and friendlier.

Catriona continued to sell shoes at a very fast rate. She found it hard to keep up with the demand. Only the day before Mayor Bottom had come in and ordered a six-inch booster, muttering something about councillors who kept growing.

Perhaps it was this background of fortune and optimism that made Emily Spark’s death that little bit harder to take. It was an accidental death—how else do 24-year-olds die?—so Chief Hardnose had to call in the coroner, Mr. Gloom.

“Well?” she demanded when Mr. Gloom tentatively knocked on her open door.

“Um…” Mr. Gloom wasn’t a confident man at the best of times.

“Spit it out, man!” Shortsbury’s improved fortunes hadn’t seemed to affect Chief Hardnose at all.

“Cause of death is, well, primarily a knock on the head…”

“And secondarily?”

“Well,” Mr. Gloom wrung his lily-white hands together. Strange to think of how many dead bodies he had touched.

“Umm, it appears the fall was caused by a loss of balance caused by… um… a pair of Catriona Sells’ shoes. The four-inch variety. Emily fell off the ladder she was working on, knocked her head on the ground and, well, died.”

“I knew it.” Chief Hardnose stood up. “Thank you very much, Mr. Gloom.”

She was on the phone before he’d even closed the door behind him.

“Mayor Bottom? I think we have a problem. A very serious problem. I’d like to address tomorrow’s council meeting.”

Council meetings in Shortsbury were dull affairs. There were only four councillors and the mayor, so arguments—when there were any—were not very heated. There was never much on the agenda, and some people felt Shortsbury could run itself very nicely without a council. Nobody could be bothered putting this on the agenda though so the council stayed.

Shortsbury gossip being what it was, word had got out that Chief Hardnose wanted to address council. That was enough to guarantee the 30 seats set out every month for the public to watch the meeting were—for the first time ever—full. And people were standing. This all threw Mayor Bottom somewhat. He wasn’t used to an audience. Remembering words of advice from his mother, he cleared his throat, took a deep breath and stood up.

“Order…” His voice was a squeak. The less compassionate in the audience giggled. Mayor Bottom turned red.

“Order.” He sat down quickly and let his secretary take over.

The meeting progressed quickly with an expectant note in the air. Item No. 6 was where people’s attention was fixed.

“The council calls on Chief Hardnose.”

The chief was up before the mayor had sat down. She walked slowly and precisely up to the desk at the front reserved for audience members who wished to speak. The microphone mounted on the front was unnecessary, but the chief still turned it on before sitting down and arranging her notes.

“Mayor Bottom, councillors,” her voice rang, slow and clear, nobody had to strain to catch a single word.

“I would like to move a new bylaw be added to our books.”

Shortsbury hadn’t had a new bylaw since 1971, when it was passed that buskers could not occupy any space on Main Street without an appropriate licence.

The audience continued to wait, holding their collective breath.

“I’d like to suggest that shoes with a height increaser be banned and all current stock be destroyed,” said Chief Hardnose.

The breath expelled, but nobody said a word. They were still waiting.

“On what grounds?” asked the mayor, glancing nervously at his feet.

“That the shoes are psychologically addictive and pose a serious health risk to the user. We have just had our first shoe-induced death”

The audience could no longer contain itself and opinions and questions broke out all over the room.

“Order… order…” Mayor Bottom stood up, paused and took a deep breath.

“The passing of a bylaw is a, um, very serious business. It, uh, can’t be decided on without all the necessary facts and figures. With this in mind, I suggest the council spends the next week getting to the bottom of this matter and we meet then to debate both sides.”

The mayor sat down in relief, barely noticing as his secretary officially ended the meeting and people began to file noisily out into the cold winter’s night.

Catriona hadn’t been at the council meeting. The first she knew of it was the following morning. A distraught looking mayor wondered into the shop at around 10 a.m.

“Morning, Catriona.”

“Good morning, Mayor Bottom.” She glanced at his shoes. “How are the new shoes? Surely you don’t want to trade up just yet.”

“What?” The mayor followed her gaze down to the floor. “Oh, no. Just thought I’d come in for a chat.”

“Oh?” Catriona looked carefully at the mayor.

“Yes, you see, last night, at the council meeting. Well, um, your shoes…”

“My shoes?”

“Yes.” The mayor stopped and frowned.

“Why don’t you take a seat and I’ll make you a coffee?” said Catriona, steering the mayor out to the back of the store, switching the open sign on the door to closed as she did so.

Over a large cup of very hot coffee, the mayor finally managed to tell Catriona about the council meeting.

“So you see, I have to prove the shoes didn’t cause Emily’s death.”

“They probably did.”

“What?” Mayor Bottom stared at Catriona. She smiled back at him.

“Electricians should know better than to wear height increasers while working, especially when they are working up a 12-foot ladder.”

Catriona sipped her coffee slowly. “So I don’t know if I can help you.”

“But, but…” blustered the mayor. “Chief Hardnose wants to ban the shoes—you would be out of business!”

Catriona put her coffee down. “I don’t think the shoes should be banned at all. I’m just saying in this particular case, the shoes probably were the cause of death.”

Mayor Bottom shook his head. “Will you at least come to the meeting?”

“Of course.” Catriona smiled softly. “After all, my business is at stake.”

Shortsbury was a hive of activity that week. Everyone had an opinion to offer on the shoes and no one was shy about offering it. The chief was busy collecting examples of people who had either injured themselves while wearing the shoes or found it hard to function without wearing the shoes. The mayor was doing the opposite. He was talking to people who had achieved things while earing the shoes or felt their quality of life had improved.

Johnny Blue-Eyes walked into the pub one evening to find Catriona sitting at the bar drinking an orange juice.

“What’s this?” he said as he sat down beside her. “I thought you only drank a pint of the finest?”

“Of course not. One has to have variety in life.”

“Oh. Well, I might order a whiskey on the rocks then.”

“Go ahead,” smiled Catriona. “It’s a free world.”

“So,” Johnny said carefully as his drink arrived, “how has business been this week?”

Catriona shrugged. “A bit slower than usual, a bit faster than usual.”

“Oh?” Johnny raised an eyebrow. “How so?”

“Some people are staying away and some are placing extra orders. “How’s your work?”

“Mine? Oh, um, fine I guess.”

They lapsed into silence.

“So what’s the deal?” Johnny asked.

Catriona glanced up. “About what?”

“The shoes! The meeting! What everyone else has spent all week talking about.”

“Oh. That.”

“Yes—that! Goddamn it, Catriona, for a woman about to lose her business, you seem pretty damn calm.”

Catriona shrugged again. Johnny shook his head in frustration but shut up.

Catriona finished her juice and stood up.

“Thanks for the conversation, Johnny.”

She walked out, leaving a speechless Johnny sitting at the bar holding a half-finished whiskey in his hand.

The meeting was scheduled to start at 7:30 p.m., and by 7:10, it was obvious no one else could possibly cram into the tiny town hall. Mayor Bottom glanced at his secretary, who nodded to him. The mayor stood up hesitantly and called for order. Silence descended immediately. The mayor looked nervously at the audience before him, drew a deep breath and began to speak.

“There is only one matter before us today, a motion to introduce the following bylaw: ‘That height increasers be banned and all current stock recalled and destroyed.’”

The mayor stopped and shuffled his feet, then his papers, before resuming. “First to speak to the motion is Chief Andrea Hardnose.”

The chief was not slow in taking her place behind the microphone, but once there, she paused, seeming to collect her thoughts. Her gaze took in the entire hall, and when she spoke, every person there felt she was talking directly to them.

“Before I start, I would like to ask a question: How many people here are wearing height increasers?”

Catriona almost laughed out loud when only about a quarter of the hall put up their hands. She turned to Johnny and muttered quietly. “Nearly every damn person in this hall has a pair of my shoes!”

The chief didn’t comment on the answer to her question, but nodded thoughtfully before starting her speech.

“I’m calling for the ban of these shoes because they are addicting and dangerous. I have signed statements from two psychologists stating the shoes are damaging to mental health, which I will read out in full.”

Someone groaned in the third row and was shot a piercing glance by the chief before she continued.

“I also have signed statements from 16 people who have suffered various injuries while wearing these shoes, including,” the chief glanced down at her notes, “one broken leg, three sprained ankles, one broken arm and one death.”

“Yeah, right,” Catriona remarked dryly. “I’m sure Emily Sparks signed that statement!”

The chief swept on, spending the next 20 minutes going into detail about the addictive quality of the shoes. She summed up with a statement from one of the local teachers who felt his instructive skills and general interaction with people was so much better when he was wearing his shoes and said he couldn’t leave home without them.

“I’m sure you’ll agree with me,” Chief Hardnose said, looking pointedly at the mayor and councillors, “that these shoes are ruining the moral fibre of our community and we must do everything in our power to stamp them out.”

The chief sat down, a smug smile planted firmly on her lips.

The mayor was next to speak.

“Well, um.” He paused and took a deep breath. “Shortsbury has traditionally been a liberal town. When other towns in the area started telling their citizens they couldn’t paint their houses in certain fluorescent colours, Shortsbury remained silent. We have always given our citizens credit, credit that they would have the wisdom to know what was good for them and the wisdom to apply common sense to all that they did. Emily did die as a result of her shoes, but she should have been wise enough to realize that height increasers and ladders don’t mix.”

Catriona shook her head and whispered to Johnny. “That’s it. The mayor is going to lose.”

Johnny frowned. “Why? He’s making more sense than he ever did!”

“Exactly. People respond to emotion and passion, not common sense.”

The mayor continued on with his speech. Catriona stayed just long enough to hear him say banning the shoes wasn’t the answer, as people would just use them illegally. Instead, people should be educated on the safest use of the shoes.

Johnny watched her go and slipped out after her. She was standing on the grass verge, staring up at the moon. He thought he saw a tear in her eyes, but could detect a subtle smile as she turned to him and spoke.

“I’ll be seeing you then, Johnny.”

“You’re leaving…”

“My lease runs out this week and I’m out of stock.”

“So, this meeting, you don’t even care. You’ve made your money and now you’re gone.”

Catriona smiled. “Of course the meeting matters, Johnny. To you, because you live here.”

Catriona turned to stare at the moon again and when she spoke, Johnny couldn’t be sure if she knew she was still there.

“Strange… you try to bring a little happiness into people’s lives, one or two get addicted or abuse it and then no one is allowed to use it. Happens every time.” Her eyes met his. “Bye Johnny.”

And the stranger walked up the road, jumped on her horse and rode out of town, into the clear winter’s night. Johnny watched her go and smiled to himself. She was probably on her way to Talleston to try and sell them a little happiness.

A (very short) Q&A with Kara-Leah Grant

The following has been edited for length and clarity.

So you were 23 when this story came out, and it’s now 23 years later. Reading it back, what does it tell you about who you were back then?

I actually started it a few years earlier than when I submitted it. I’d been in London, at 21, for a couple months and got immersed in rave culture for the first time ever.

So I was going out in my early 20s and grew up being told that drugs were bad and only bad people did drugs. It was a real contrast between what I had experienced growing up and what I had experienced in London. So I think the story was written as a way to make sense of that conflict, to explore the idea drugs aren’t inherently bad. It’s your relationship to them and how you use them. It’s an allegory.

Also, when I read it now, the first thing is I want to edit it. I want to make it way tighter. [Laughs].

Whistler has obviously undergone so much change since then. Paint us a picture of what the Whistler of 1999 was like for you back then.

It really felt magical and it felt connected. It felt like there was a community. I would wander into the village and I was guaranteed to run into people I knew who were doing fun and exciting things.

It was just a sense of home and community and connection and a real integration with the land as well. The mountains and the forests and the lakes and the Valley Trail. And in some ways, that village life that I talk about in the story is a little like the village life of Whistler back then. Shortsbury and Talleston definitely have similarities with Whistler of that time, even though it was written before I came to Whistler.

Kara-Leah Grant is a tantric instructor and public speaker who has worked with hundreds of clients over the years. A former freelance journalist, she is the author of three books and an award-winning screenplay. Learn more at karaleah.com.