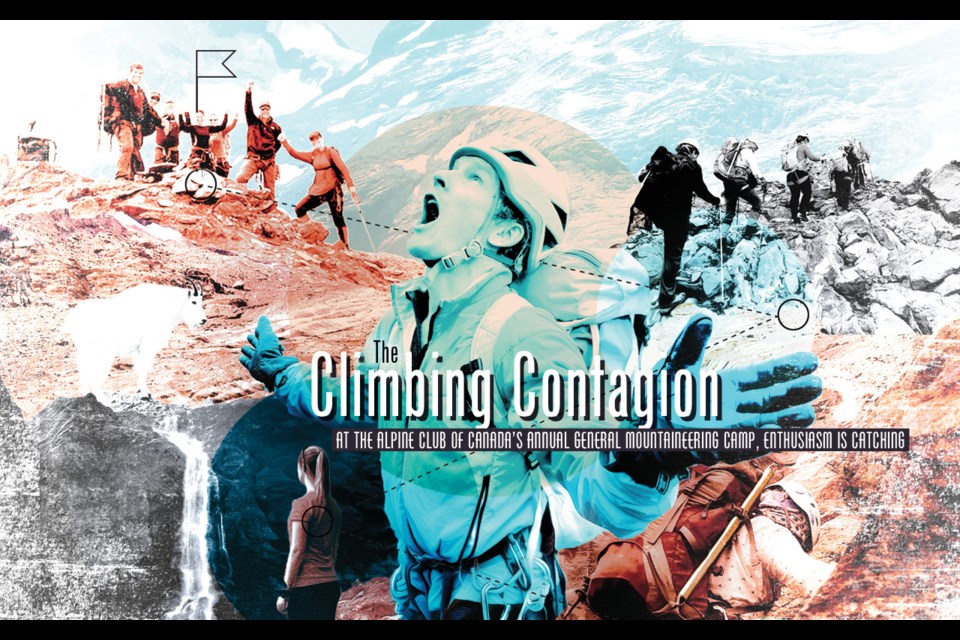

It’s a quintessential British Columbia scene: a scatter of people, a heap of gear, a helicopter, and someone plucking a Spanish guitar in the background and singing like an angel—all swathed in a gentle rain pattering down through a veil of wildfire smoke.

It’s Day 1 of our week at the Alpine Club of Canada’s annual General Mountaineering Camp (GMC), and the big swap is underway—36 people flying out with baggage, garbage, empty gas cylinders, blisters and sore muscles; the same number flying in with an even larger load including food and other camp supplies.

The 2018 edition of the 111-year tradition is taking place at Hallam Glacier in the Monashee Mountains north of Revelstoke. We’ve driven three bumpy hours from town to the staging area to await our turn in the rotation amidst what seems an endless series of heli-shuffles, refuellings, and baggage-only flights. When we finally do lift off, four hours after arriving, the pilot expertly navigates the thick smoke by shadowing valley walls, ridges, and streams all the way to camp, set high on a moraine near the toe of the glacier. We debark into what can only be described as a marvel of modern wilderness technology, featuring solar panels, rudimentary plumbing, propane kitchen appliances and showers, a portable drinking-water treatment plant, sinks with bladder pumps, comfortable latrines, and large tents for cooking, dining, storage, drying, and even a library, the rocky surroundings constellated by some 30 roomy nylon tents for campers and staff. Though occupying a similarly stark setting, it makes Everest Base Camp look like a low-tech ghetto.

Speaking of which, the glacier hanging above us is mesmerizing on a Himalayan scale, its fractured blue depths exacerbated by the melting snows of late summer. Ringed by mountains, Hallam Glacier flows off an icecap that requires a 1,200-metre vertical climb to reach before even thinking of attacking its surrounding peaks. My body quivers at the thought of how much pain this might entail, while others salivate at the prospect. As with the GMC’s five previous one-week occupants, our group is an eclectic mix from around the continent that includes camp veterans, high-functioning mountaineers, and relative novices like myself.

The intimidation I feel is real, but I convince myself I’ll get over it. After all, challenging oneself is the point of mountaineering.

The slow ascent

The storm hits around 2 a.m.—spectacular lightning, driving rain, howling winds, little sleep. Nonetheless, by 6:00 a.m. the dining tent is buzzing with folks who can’t wait to get at it. It’s weird to see so much enthusiasm at a time of day when most of us are zombies awaiting our caffeine fix—but it’s also invigorating.

With a choice of objectives to sign up for each night, I’ve joined the “skills group” today—folks looking for refreshers or introductions to simple ropework, rock-climbing, and glacier travel. After an organizational talk we head out with amateur guides Jesse Milner and Bree Kullman, crossing the valley to a wall of glacier-polished rock hung with a 120-m curtain of water whose echoing cascade—lightning interruptions notwithstanding—provides perfect white noise for sleeping. We cross a stream on a rope-and-ladder bridge, pick our way through rocks to the wall, and harness up (“transitioning,” according to the guides’ lingo) to begin the slow ascent through a system of ledges (or “rock steps”). Safety ropes have been fixed in places where exposure is an issue and so, suddenly, “situational awareness” becomes key. Already high above camp, a fall in some spots could be fatal, requiring you to pay maximum attention to foot and hand placements. Oddly (or perhaps not), learning to manage the seriousness of alpinism seems to increase the enjoyment.

Eventually hands-on rock climbing is required, and we rope up as a team. After Jesse ascends and sets an anchor we follow, 10 m apart. The rock remains greasy from last night’s rain, but it doesn’t take long to clip around the first bolt and move upward. At the top we exit the rope onto a small plateau, then spend an hour hiking over a steep ridge to a lake constellated by icebergs calving from a rapidly retreating glacier.

We circle the basin, first on sand then crumbling moraine. Just before the point where the glacier’s icy tongue looms over the frigid lake we hit “dry glacier”—a stretch that looks for all the world like rock and dirt but is riven with channels gushing meltwater from ice stranded beneath the rubble. On the glacier proper we rope up into teams, donning crampons and ice axes for walking. Hail from last night’s storm has gathered into odd patterns on the glacier’s surface, in some places frozen into puddle-like display cases.

At the glacier’s headwall the real clinic begins, as we practise setting and retrieving ice screws and self-arresting with ice axes during pretend falls down a snow slope. As per mountain dogma, we turn around at 1:30 p.m. for the long slog back. Everyone returns sore but in good spirits from a first day out, and we set to lounging outside the tea tent with other returnees. Snacks and beer and stories spark the familiar camaraderie of the mountains—one of the reasons so many attend these camps year after year.

At dinner—a raucous but delicious affair featuring gourmet-level food—we meet our Association of Canadian Mountain Guides (ACMG) leaders for the week. The all-star crew includes climbing legends Helen Sovdat and Ian Welsted; Alberta Parks public safety specialist Matt Mueller; former Parks Canada visitor safety specialist Paddy Jerome; and Cyril Shokoples, past ACMG president and chief instructor of the Canadian Forces Search and Rescue Technicians for the past quarter century.

Afterward, I take my first crack at communal dish duty, an industrial enterprise of several hours requiring six people to execute washing, disinfecting, rinsing, and drying. By the time I get to my tent, I’m asleep before I can pull the zipper down behind me. Fortunately, there are no bugs at this altitude.

The Hallam High

Next day, groups that signed on for big objectives wake at 4:30 a.m. and leave camp within the hour. With bruised feet from my shakeout climb in rental plastic mountaineering boots, I’ve decided on a lighter day of hiking around camp in my own well-broken-in footwear.

The climb to the Hallam’s high moraine starts just behind camp and heads straight up. At the top, the trail meanders upward through the preternaturally green meadows of “Waterfall Alley,” a chunk of bucolic lushness in an otherwise stark alpenscape. Here, water braids thinly over at least four different kinds of rock, highlighting the multifarious folding and buckling the Monashees are famous for. Heading up a gully, I stick close to the shaded wall to avoid rockfall, then traverse onto the moraine. The trail, marked by rock cairns, now steepens significantly. At the top cairn, prodigiously—or perhaps mockingly—decorated in birdshit, the view to Hallam Glacier is stupendous. Far below, colourful ants dot its icy toe—a crew of University of Alberta students on an outdoors course practising crevasse rescue. I can also see across the valley to Iceberg Lake and the route traversed the day before. Such constantly evolving perspectives of mountains are one of the best features of travelling in them.

On the way down, I meet another lone traveller. Dr. David Hik is a terrestrial ecologist from Simon Fraser University and long-time ACC member teaching a module for the U of A course. He’s scouting places to bring the students and we sit on a rock to watch a ptarmigan family and chat ecology; climate change—the effects of which are starkly visible here in melting glaciers, lowering water tables, wildfire smoke, and changing ranges of plants and animals—dominates the discussion. The only comfort we can take away is knowing that when it comes to climate awareness, this is a classroom par excellence: mountains breed curiosity, the curious are environmentally conscious, consciousness begs information, and information fosters concern.

Back at camp, as climbers return, reports of conditions flow in with them: two crews aiming for the big peaks above Hallam Glacier couldn’t solve the crevasse “riddle” on its rapidly melting surface and had to turn back; another group that struck out for Wiser Peak is moving slow and won’t return before sundown.

It’s all grist for the guides in figuring out the next day’s offerings.

Curiouser and Curiouser

Still nursing blackened toes, I’ve signed onto something moderate—a climb to Bombay Peak. Though the first night’s thunderstorm briefly cleared out the smoke, the province’s abundant wildfires—including new ones sparked by the storm—have made themselves known again. A blood-red sun hangs in a thick gauze of smoke that worsens as the day wears on.

Helen Sovdat and amateur guide Peter Findlay lead us up the same rock step I’d climbed previously. Despite having an extended family of seven from Barrie, Ont., with us—paterfamilias Rob Hamilton, two daughters plus the husband of one, a son and his wife, and a son-in-law married to a daughter who isn’t here—the climb goes more quickly than the first day and we gather at the top to angle up a tumble of slick, heavily glaciated rock. As we scramble up a tricky section someone yells, “Goat!” We gaze up to see a huge male perched on a promontory, ears twitching at a torturous halo of flies, staring us down in curiosity. Even when we close to within 20 m it doesn’t move, as if it knows our route will take us around him.

Above the goat we climb onto a balcony abutting glacial ice, then step gingerly onto its surface. This glacier is dirty and heavily crevassed, so we follow these wounds laterally until we hit a main gully we can head up without much worry. The higher part of the glacier surrounds Mount Joy, little more than a tiny nunatak from this distance, but we’re heading in the opposite direction, toward the col between Bombay and Wiser peaks.

Near the end of the slog, Helen punches through collapsing snow into a small crevasse, gingerly reversing her steps and poking around to find a more solid route. We skirt the crevasse and, a few steps later, step off the ice onto the rock of the col. From there it’s 20 minutes along a spectacular ridge to the 2,400-m summit of Bombay and impressive views in every direction—though we can see little more through the smoke than the fractured glacier we’ve just climbed.

Lunch is a joyous celebration for the Hamiltons, who’ve accomplished this together; 73-year-old Rob has had two heart attacks and is on blood thinners, and a small nick on his head bleeds profusely as he poses with a funny-looking bandage for the family photo. We hang on the peak for 45 minutes before Peter pulls the plug, splitting the group based on desired speed of descent and hectoring the faster squad onto the trail zigzagging down the ridge.

At dinner, more stories are shared. When it’s the guides’ turn to reminisce on previous GMCs, Helen tells the story of her first, when the helicopter with all the gear didn’t show up because the pilot got lost. Everyone spent the night out around a fire, but in the morning, despite little sleep, everyone still wanted to climb. Seeing such commitment in the face of adversity, Helen had immediately known she wanted to be a part of it.

That kind of tradition, 111 years strong at this point, is contagious indeed.