Hot springs are a hot topic in this neck of the woods. We've all heard mention of them, typically in hushed tones, people talking about their latest excursion into the backcountry for a soak "somewhere up past Pemberton."

B.C. is actually relatively rich in springs when compared to the rest of Canada, and here in Sea to Sky we have a few to pick from. Aside from bigger, popular sites like St. Agnes Well (also known as Skookumchuck), Sloquet and, of course, Meager Creek, there are also lots of little, lesser known springs scattered throughout the region. Ever heard of Placid, No Good, Glacier Creek, or August Jacob's (Franks)? Didn't think so.

There are anywhere from 110 to 126 hot and warm springs that are known within the entirety of Canada. Of those, 86 are here in British Columbia, and they range from the partially and fully developed commercial sites of Harrison Hot Springs to undeveloped wilderness springs - some of which aren't suitable for bathing but are nonetheless sought out by avid hot springs enthusiasts, just for the thrill of the hunt.

Of course, Canada's numbers pale in comparison to the thousands that exist in other countries. Japan (which is just about half the size of B.C.) boasts 22,000 springs, while Italy, Turkey and Greece are also known to have a rich and healthy hot spring culture.

The science behind the springs

Glenn Woodsworth, a noted geologist and research scientist with the Geological Survey of Canada, wrote the book on the topic of hot springs - quite literally.

He first became interested in hot springs while working throughout the province as a geologist.

"It basically comes out of my geology and backcountry experience, which is strong in mountaineering and coastal explorations," he explained.

Woodsworth actually authored the first guide to summiting the Stawamus Chief and took over the project of "Hot Springs of Western Canada" from his predecessor, a former prospector named Jim McDonald who published the original version of the book back in the '70s.

Today, Woodsworth is putting the finishing touches on the third edition of what has become the bible for hot springs enthusiasts here on the West Coast. He's been collecting information and tips from fellow soakers since the second edition came out in 1999 and has most recently been making trips to many of the larger springs he mentions within, ensuring that his information is accurate and up to date. Talk about painful research.

Woodsworth explains that hot springs are located on geologically active areas, and in North America most are found in the mountain belt that runs from Alaska to Central America, over top of the "Ring of Fire" that encircles the Pacific Ocean.

The earth is hotter below the surface and the temperature rises the deeper you go. That heat actually comes from buried bodies of molten rock, which are cooling, and from the slow, constant decay of radioactive elements like uranium, thorium and potassium. This means that hot springs are nuclear powered. Now before you panic, Woodsworth points out that radiation levels in springs are far too low to pose a health hazard.

Rainwater and melted snow penetrates through cracks in rocks below the surface of the earth where it is heated and pushed back to the surface as hot water by a gravity feed of cold water, which drives the less dense warm water upwards. A hot spring is born.

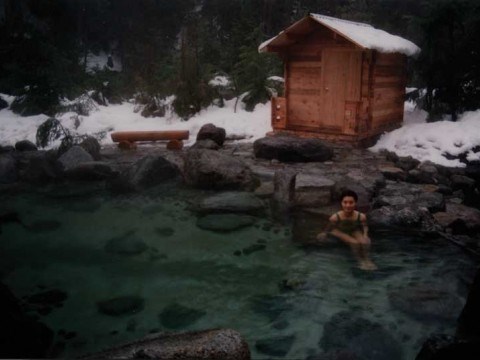

Soaking in Sea to Sky

Aside from offering a relaxing experience and an opportunity to commune with nature, hot springs are also rumoured to hold unique health benefits because of their high mineral content, which includes everything from calcium to lithium and radium. These minerals are supposed to raise energy levels, increase metabolism, accelerate healing, improve circulation, and detoxify the lymphatic system, and are used therapeutically to treat chronic fatigue, eczema and arthritis. Our local springs also boast unique ecosystems, and are home to a range of wildlife - from mountain goats and grizzlies to some very rare flora and fauna.

Norbert Greinacher is a recreation officer for the Recreation Sites and Trails Branch of the Ministry of Tourism, Culture and the Arts. He's one of just 18 recreation officers in the entire province, and he covers the Squamish Forest District that extends all the way up to Bralorne and Gold Bridge. He's worked in the Forest Service for over 27 years, calling the Squamish area home for almost 12, and in that time he has become well-acquainted with our local forests.

"These are the ones that I'm aware of," Greinacher said, gesturing to a large folding map of the district.

Only three local springs fall under his jurisdiction: Sloquet and Meager are established Forest Rec sites, while the third, Pebble Creek or Keyhole Falls, is a UREP site (Use Recreation and Enjoyment of the Public). The St. Agnes Well springs were privately owned by the Trethewey family for almost 50 years, but in recent years were purchased by the government and have subsequently been leased to the In-SHUCK-ch people. Eventually, Greinacher believes they are going to be part of the In-SHUCK-ch's treaty settlement agreement.

"St. Agnes Well is named after Agnes Douglas, who was the daughter of Governor (James) Douglas," Greinacher explained, "He ordered the first highway in the province built."

That highway, the gold rush trail, was the main access to the gold fields from 1859 to 1863. The area's natural hot springs were one of the few luxuries available to these pioneers, offering a respite from bitter winters and a place to soothe their aching muscles.

"The miners used to talk about this being the only free pleasure in B.C. because you can imagine, when you're hot, sweaty and you probably got a cold along the trip, depending on the time of year, you could soak in the hot springs," said Greinacher.

Many of the springs, like St. Agnes Well, are of a great cultural and spiritual significance to the local First Nations people, who enjoyed the pleasures of a soak long before the white man came along.

The forest service roads leading to Meager, Sloquet and St. Agnes Well are graded and maintained by logging companies or more recently, by companies working on independent power projects in the region, but Greinacher said flat tires are still a common occurrence, even when the roads have been maintained.

"What typically happens is people are fine when they get one flat, but it's not uncommon to get two flats in a day, and then you're hooped," Greinacher said, pointing out that there's no cell reception in these areas.

As Greinacher so eloquently surmises, Sloquet is more of a "rustic experience," with minimum maintenance and supervision from the Forest Service.

"I'm not sure how much longer we're going to have the Sloquet hot springs," Greinacher added, pointing out that this site is again part of a treaty package that has not yet been ratified with the In-SCHUCK-ch Nation.

But what about the smaller sites?

Placid and No Good are hard to find and tiny, and you can't bathe in them, so unless you're just looking for a challenging trek Woodsworth doesn't advise seeking them out. In fact, there are even some that are downright dangerous to get to.

"Keyhole, or Pebble, is good," Woodsworth added. "It's not too hard to get to. You can't drive to it, and you've got about a 10, 15 minute steep walk downhill."

A few bad apples can spoil the bunch

Hot springs enthusiasts seem to have created an almost clandestine culture when it comes to revealing the locations and secrets about their favourite soaking spots, and Woodsworth actually admits to wrestling with his own instinct to keep his in-depth knowledge about our springs to himself, versus sharing it with the public.

One of the reasons behind this secretive culture may be hostility towards the few that seem to disrespect the springs when they visit.

"There's been an unfortunate tendency, and Meager's a really good example of that, of people that go in and they just trash these places," Woodsworth said.

Back in the day, Meager used to see as many visitors as commercial springs in Jasper National Park - up to 12,000 visitors per year. In 1993, Sato said 35,000 people actually visited the site.

"There was just nobody there (supervising) and you get the six-pack crowd," Woodsworth recalled. "I was there once on the July long weekend and there were knife fights going on, and there's broken glass in the pool, and drunken brawls."

He adds that hikers and climbers in the Whistler and Vancouver area tend do the same thing as soakers when it comes to protecting their secret spots and cabins.

"I take a different approach to it," Woodsworth said, pausing thoughtfully. "I have a little more faith in the public - not in the yahoos and the ghettoblaster crowd - but in general, I do. I think that if we're going to make all these complicated land-use decisions, whether it be run-of-river or what to do with the hot springs or logging or fisheries or anything else, then the more people that know about the problems and issues the better."

Opting for the "knowledge is power approach," Woodsworth decided to emphasize the environmental responsibilities that all users should respect when visiting any hot spring, pointing out that as more people visit these sites the more strain is put on sensitive ecosystems.

Meager Creek's "checkered past"

Meager is the crown jewel of local hot springs, but it also has a colourful history. Located in the headwaters of the Lillooet River about 70 kilometres northwest of Pemberton, it's considerably more accessible than, say, Sloquet, though visitors still have to travel along a fairly rough logging road to reach the site.

"Meager Creek is probably the best known because of the relative ease of access. People will come from Vancouver and do it in a day," Greinacher said.

"It's had lots of publicity," he added with a slight grin. "I swear, in this office, it's got to be the biggest file - I mean, there's volume after volume of stuff on Meager, all the studies that have been done. It's got a checkered past."

The trouble first started in the late '70s when loggers came into the picture.

"There were some clashes between the loggers and the people that didn't like logging and everything else," Greinacher recalled. "People would vandalize logging equipment and then they'd come back with their machines and wipe the primitive pools out."

But its position atop a very active debris field has been the most troublesome issue over the years. The volcanoes in the area erupted just 2,400 years ago - essentially a blink of an eye in the geological world - and everything is still shifting, seeking equilibrium. This often results in tens of thousands of dollars in damage.

"This whole Meager system is very geologically unstable - its one of the most geologically unstable areas in Canada, if not North America," Greinacher pointed out.

In 1974, four people in the area doing research on geothermal potential for BC Hydro and the federal government were killed by a slide. Then, in 1984, there was a slide that went through the area over a long weekend, covering cars in gravel and stranding visitors.

"Luckily, no one got hurt so because of that, the use - when we think its safe to use - is restricted to day-time only, there's no longer camping provided there," Greinacher said.

Polishing the crown jewel

Back in the early '90s, the Meager Creek site wasn't being managed properly. There were loads of people partying at the site, fights, vandalism and, eventually, health concerns followed. Governmental officials panicked, fearing liability, and in the summer of 1995, the Ministry of Health declared that Meager was dangerous because of elevated fecal coliform levels, and subsequently drained the tubs in November.

To deal with these problems, public meetings were held in Pemberton, Squamish and North Vancouver, attracting crowds of over 220 people. From 1995 to 1997, several hundred complaints regarding the closure of Meager Creek were sent to the Forest Service.

Clearly, something had to be done. Forest Service ended up using money from the Forest Renewal B.C. program to enlist the help of a private contractor to revitalize the site. Enter Mike Sato.

"All complaints were about the police and B.C. Health activity; not a single complaint had any suggestions that could lead to the improvement of Meager Creek hot springs," Sato pointed out. "None of them even came close to mentioning the B.C. Health (regulations), or ways to meet minimum health standards, overcoming the water quality issues, or whether to create a natural pool."

Originally from northern Japan, Sato is no stranger to the hot spring culture. He moved to Canada in the '70s and to date, has visited 88 hot, warm and mineral springs in this country. The remaining 40 springs that he hasn't hit yet are spots that have not been visited in almost 100 years, and may only exist in old reports and prospectors' maps.

Sato actually began working as a consultant on B.C. hot springs development back in 1988, after he was contracted by a Japanese financial institute, and launched his own company - Sea to Sky Onsen Inc. - ten years later, specializing in the development of Japanese style hot springs facilities.

Meager Creek's problems first came to Sato's attention back in the early '90s. In March 1996, Sato sent a letter to the Forest District outlining a few suggested scenarios for the future of Meager. Because of its remote, isolated location, Sato felt that Meager couldn't be developed as a commercial site, as it couldn't operate year-round. Instead, he recommended that a wilderness hot spring model be implemented. But the process wasn't as straightforward as he had hoped.

All natural hot springs on Crown land fall under regulations in effect for swimming pools and spas, which means they require disinfectant.

"Many pools are actually natural pools ... and those that are, are usually not allowed for public use because they will have issues of not having met the minimum health standards, unless the water flow is great like the Liard Hot Springs (in Northern B.C.)" Sato explained, adding that Liard also had little to no artificial elements.

Sato points out that if natural hot springs are to be made into general public-use pools, they would need to meet minimum health guidelines, which means that they will require at least some man-made improvements. But once those improvements are made, the pools become artificial and fall under regulations.

To get around the provincial requirement to chemically treat the springs up at Meager, the pools would have to be classified as a natural pool, which isn't subject to the Water Recreation Facilities regulations. Sato realized that the two existing large cedar pools, which were artificial, man-made structures, would have to be replaced with natural pools - a difficult proposition, to say the least - in order to qualify for exemption. To date, Meager is the only spring that has been granted full exemption from public swimming pool regulations.

"Other locations, such as Hot Springs Cove (Maquinna Provincial Park) at Vancouver Island (and) Liard River Hot Springs Provincial Park at Alaska Highway, are user-fee charging operations that did not need to comply with B.C. swimming pool regulations because they are classified as natural pools not artificial," Sato explained. "Which is why they are allowed flow-through pools that are not chemically treated."

Today, at Meager, the water has a constant flow-through and the Forest Service regularly samples the water to ensure it's safe. Plus, the way that the pools have been designed, they can be easily drained, power washed and refilled in a two-hour window.

Sato's records on the process of revitalizing the Meager springs are staggering. He has compiled all documentation - letters, newspaper clippings, you name it - surrounding Meager Creek from 1992 onwards. The result is a two and a half-inch-thick bound collection of material.

After all of his hard work, storms in October 2003 washed away the bridge to the Meager springs, rendering it inaccessible until the new bridge - valued at $900,000 - was finally completed last year.

"And it's in a location that it could last a year or a hundred years," Greinacher pointed out.

Today, Greinacher and the rest of the Forest Service have a set of shutdown procedures in place if they notice the water temperatures spiking, or if they receive a high level of rainfall. They've also established a separate campsite away from the springs, but nearby in a safer location.

"There's a fair bit of understanding where the areas are of greatest risk," Greinacher added.

Meager was reopened in August of last year for the first time in five years, and this year, the springs were opened to the public in late April, and should remain open until the fall, closing sometime towards the end of October.

While Greinacher didn't have exact numbers from last year or this year, he said in a typical summer, Meager will attract over 6,000 visitors.

There's now a $5 fee for using the hot springs and a $10 charge to stay at the campsite, with money collected used to offset the cost of management and maintenance. Sato believes that this user fee helps ensure that the people who are visiting the springs respect the site and the surrounding area. By many accounts, the new systems seem to be working to help control visitor behaviour and mitigate health and safety risks.

"I think we're attracting a different person, less of a party crowd," Greinacher reflected, "We used to have some pretty wild parties up there; people would take cannons up there and shoot them off at night!"

Where there's steam...

It's a common Japanese method to drill for hot water and create your own springs. But here in B.C., almost all of our springs are naturally occurring.

While scientists and soakers like Woodsworth have confirmed the existence of many springs here in B.C., the pools are, literally and figuratively, fluid entities, with old ones drying up and new ones breaking through the surface over time.

"Some of them also come up in or close to rivers," Woodsworth said, adding that in many of these instances, the hot springs are never discovered, unless its stumbled across by a passing swimmer who happens upon a warm spot in the frigid waters.

There are about a half dozen people within the province who actively seek out the rumoured springs - Sato and Woodsworth are just two of the enthusiasts dedicated to the task. They seek out reliable sources, even take helicopters out in the winter, looking for telltale wisps of steam, and hike for hours, all in an effort to confirm the existence of a spring.

"Some of them are just rumours, like there's supposed to be one up Callaghan Creek somewhere," Woodsworth said.

There are actually quite a few supposedly undiscovered springs in the Sea to Sky region, but Woodsworth points out in some cases, the rumours are just that - rumours.

But the geologist recently discovered one such reputed spring here in the Sea to Sky, August Jacob's, though it isn't one big enough to bathe in, and it takes about a four-hour hike into a steep canyon to reach it.

Another elusive local spring is Glacier.

"Glacier Creek almost certainly exists. That's one of the springs in the 'rumour' status, but I've made a few attempts to find that thing, including flying over in a helicopter in the dead of winter, looking for the steam and stuff like that."

He's discovered an old mining claim map from around 1898 that shows Glacier Creek springs marked on it, so he's convinced that this lost spring actually does exist.

"Some of the people in Mt. Currie say, 'Yeah, my grandfather used to go to that, they knew what it was, but I don't know where it is.'"

The future of the springs

Mt. Currie has been given the partnership agreement to manage the Meager Creek site along with some of the other rec sites they manage for the forest district, and it seems as though Sloquet and St. Agnes Well may soon become property of First Nations under treaty negotiations. The Sea to Sky Land and Resource Management Plan also mentions that the In-SHUCK-ch Nation have until July 2012 to complete an economic development strategy for a "cultural site" located at Franks Creek.

So is there room for further development or commercialization of our local springs?

Aside from traditional uses, Woodsworth points out that the hot springs hold great geothermal potential. In fact, B.C. Hydro and private companies have already invested millions of dollars investigating the geothermal power potential at the Meager site, and similar investigations have been made at Mount Cayley.

Here's how it works, basically: several drill holes would be made, reaching several kilometers below the surface. Then, water is pumped down one hole and heated up naturally, pushed back up to the surface in the form of steam and hot water, and forced back down another hole. The water is continuously circulated, creating a heat exchange that can be used to generate electricity.

"It's clean and it basically works - it produces nothing except hot water, which gets pumped back into the ground. No greenhouse gases, no nothing," Woodsworth said, adding that he has no affiliations with geothermal companies. "...I think the potential for power at Meager is actually quite good."