Standing on the frozen shoreline on an impossibly sunny day in early March, Alta Lake is nothing less than idyllic.

The sun reflects blindingly off the blanket of snow spanning the lake, disturbed at the moment only by a pair of cross-country skiers, silently gliding in different directions.

Aside from some clattering and banging coming from a nearby construction site, it’s a perfectly tranquil scene when viewed from the back of Lawrence Keith’s deck.

But Keith knows the peace won’t last.

Living immediately next door to Lakeside Park, Keith has seen visitor numbers to Alta Lake explode in recent years, as Whistler truly comes into its own as a four-season resort.

At the same time, he says, commercial operations in the park beside his home have only expanded.

“This encroachment keeps going. It keeps pushing. Every summer it’s further,” he says.

“There doesn’t seem to be any restrictions or control over any of it. It hasn’t been well thought through as to its impact, and it just seems to be growing, like a monster.”

Further, in Keith’s mind, there doesn’t appear to be any overall plan to manage the growth, “and when there is a plan, they don’t stick to it anyway,” he adds.

On a patio table on Keith’s back deck, the longtime local has laid out maps of the original Lakeside Park management plan, as well as a binder nearly bursting with documentation and correspondence stretching back to the early 2000s.

He points to a raised berm that was designed to protect his property from park noise, then to a space beyond the treeline where a shed was installed without warning in 2016 by cutting into the berm.

When he emailed the Resort Municipality of Whistler (RMOW) to ask them to fix the berm—designed as a noise buffer for his property—Keith was told two trees that were removed would be replanted in a week.

Five years later, Keith is still waiting for the vegetation to be replanted.

It’s possible the shed itself was constructed illegally, as the LP1 zoning of Lakeside Park dictates that no structures be built within a 10-metre setback (the RMOW said it was unable to respond to several questions posed on April 26 about the legality of the shed, and other “scope-creep” issues in Lakeside Park, after a ransomware attack took services offline on April 28).

There are other concerns, too: boat launches have only become more frequent, often using the north side of the public dock (something they aren’t meant to do, Keith says); a handrail included in the original drawings of the dock was never installed, while the dock has been expanded; the berm itself was never extended to the road, leaving space for noise to seep through; public canoes are stored just metres from Keith’s property line, inside a 10-metre setback; and increased numbers of Valley Trail users en route to the park, representing a safety issue in the neighbourhood.

For his part, Keith doesn’t want to be a troublemaker. Having owned his property by the lake for close to 30 years, he’s spent nearly half of them quietly combatting the municipality on issues of noise and privacy.

More recent attempts to parley with Mayor Jack Crompton and council have been met with disinterest, or unsatisfying answers, he says.

Last summer, as crowds of Lower Mainlanders and locals flooded Whistler’s parks in search of a pandemic escape, Keith decided enough was enough, and started a petition calling for the end of commercial activity in local parks.

The petition has so far garnered more than 675 signatures.

“I don’t really wanna be in a big fight with everybody, but I don’t think I have any other choice,” Keith says.

“This is really my last opportunity without taking some type of legal action. I don’t see what else I can do.”

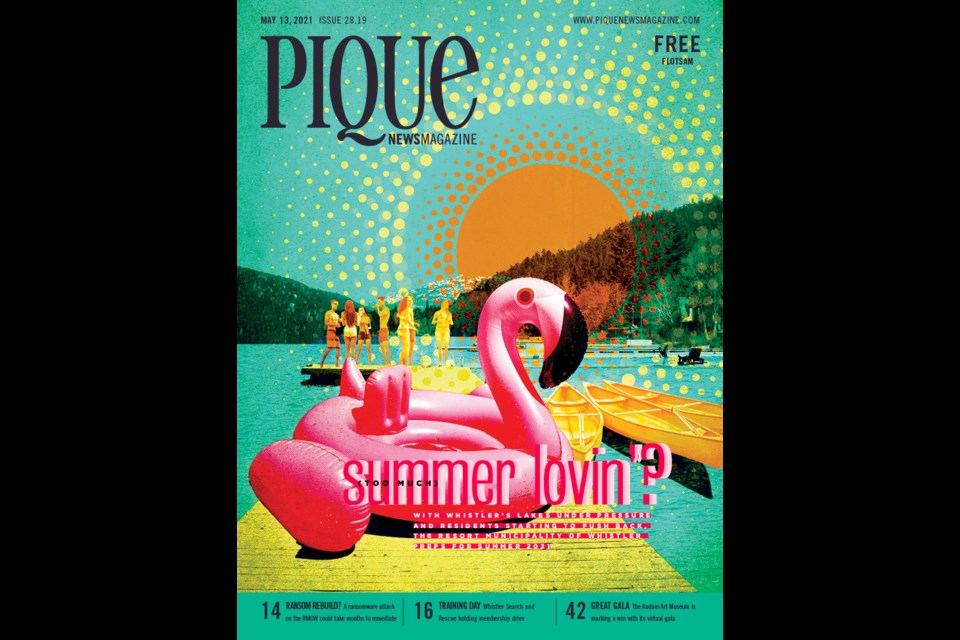

While at the root of it, Keith’s conflict is between himself and the municipality, it is emblematic of a larger trend in Whistler: As the resort comes into its own as a fully realized, four-season destination, local lakes and parks are under immense pressure.

What is the RMOW doing to keep up?

‘THINGS JUST GET BUSIER AND BUSIER’

Though Keith has yet to formally deliver his petition to municipal hall, banning commercial use of parks is not something Whistler’s mayor is supportive of, and it’s not something council plans on considering in the short term, at least.

“It may be hard to imagine, but 15 years ago Whistler was a place people visited in the winter, not the summer,” Crompton says.

“Our community spent a huge amount of time and energy becoming a four-season resort. We diversified a very much winter-only tourism economy into one that could support jobs and families year-round.”

But that’s not to say the issues raised by residents like Keith are being ignored, Crompton adds.

“I don’t want to diminish the concerns about how these community amenities like parks and trails are managed. We need to consistently focus on how we can be better every day,” he says.

“I’m confident our staff have their minds turned to consistent iterative improvements—how we can be better every day? How we can be better every summer?”

With that in mind, RMOW staff is taking lessons learned from last summer—when local parks were overwhelmed with people desperate to get outdoors after months of COVID-19 isolation—and applying them to the upcoming summer.

On March 16, council endorsed a new 2021 Summer Experience Plan, which lays out a number of key initiatives to help manage capacity in parks and at trailheads.

Key among the proposals is the introduction of seasonal pay parking at four parks (Rainbow, Lakeside, Alpha and Wayside); regular shuttles to Rainbow Park (with stops at Meadow Park and the Rainbow Lake Trailhead) operating out of the Day Lots; privately-operated bike rentals; expanded bike valet services; enhanced animation to help disperse crowds throughout the valley; and an increase to washroom facilities, garbage and compost bins, food service and park hosts.

“For Whistler, our lakeside parks, in particular Lakeside and Rainbow, are two of those really key destinations for visitors … They are destinations that are meant to serve not just locals, but our guests, and they are busy,” says general manager of resort experience Jessie Gresley-Jones, adding that the RMOW is being “proactive” in managing park use this summer.

“So we’re looking at ways to manage parking; ways to facilitate guests getting to and from the parks sustainably, and safely; looking at ways to have more storage opportunities, and ways for locals to still use the parks effectively and be able to get there without needing to also drive and encounter what might be a very busy parking situation,” he adds.

“And so the summer plan, I think, is being quite comprehensive in its strategy, to try and tackle a lot of the issues that came up last summer with quite a different summer experience.”

As it relates to the specific concerns raised by Keith, the RMOW continues to monitor the situation and consider the feedback it receives, says manager of resort parks planning Martin Pardoe in a recent tech briefing.

“Our intent is to provide a safe experience for people, and a remarkable experience. We are in the resort business; we are the ‘resort municipality,’ we’re not the ‘town of,’ and we’re obliged to provide that,” Pardoe says.

“At the end of the day, we have a destination resort park that is very desirable for people to go to, and it provides a great resource for our community.”

Safeguarding local lakes is an ongoing focus at the municipality, and is made more difficult by jurisdictional overlap: while the municipality controls lakeside parks, B.C.’s foreshores are the jurisdiction of the provincial government, and the water itself is governed by the federal government.

“That is a challenge, but we work together with our partners,” Pardoe says, adding that while lake and park use is increasing, the RMOW has been “fairly strong” through its Recreation & Leisure Advisory Committee in turning down applications for bigger, more intrusive commercial operations at Whistler’s lakes.

One such example was for an “electrified, overhead automatic wakeboarding system,” Pardoe says.

“We didn’t feel the need to add additional busyness,” he says, noting that the RMOW recognizes the importance of protecting local lakes where it can.

“[But] like everything in life, it gets busier over time,” Pardoe says.

“There’s more people living here, there’s more people living in the Lower Mainland, and there’s more people coming to Whistler over the years, and things just get busier and busier.”

A four-season success story

Keith’s opposition to the expansion of Lakeside Park is not new, if happening mostly in the background in recent years. He was one of several outspoken critics as the park was being developed in the mid 2000s.

According to stories pulled from Pique’s archives, the issue of commercial operations in the residential neighbourhood has been at the heart of the opposition from the outset.

Eric Wight, owner of Backroads Whistler, which rents out canoes, kayaks and paddleboards, has been operating out of Lakeside Park since 2006.

Since then, it’s gone from a small neighbourhood park with boat rentals to a major park in the Whistler Valley, Wight says.

“Most of the locals I talk to go, ‘You know what? We were a little bit worried about it at first, but it’s been great. And for 10 months of the year, we’ve got this park that no one uses, and two months of the year it’s a resort and we expect people to come to the park,’” he says.

These days the number of guests he welcomes each summer is mostly steady, depending on the weather.

“Since 2012, we’re not seeing mass year-over-year increases [at Backroads Whistler],” Wight says.

“The park is getting busier with the general public, for sure.”

The RMOW does not currently track user numbers in parks, but has earmarked $275,000 over five years in the 2021 budget for a data collection and monitoring program “to be used [for] asset management, inform decision-making and long-term planning purposes.”

As it relates to Keith’s concerns, Wight says Backroads has made efforts to address issues and mitigate its own impact where it can, including installing padding for canoe racks, but the private business can’t be responsible for the general use of the park.

“[Keith] is really on us about noise, but I really don’t think I’m his noise problem,” he says. “Lakeside Park has become very popular to the general public … People are coming down, and it’s a park, it’s a resort, they’re having fun.

“If you took the boat rental operation completely out of Lakeside Park, completely gone, is that going to change the noise level?”

It’s another example of Whistler perhaps being the victim of its own success, Wight adds.

“Whistler is a wonderful place to visit. It’s a wonderful place to live, and being a resort town, we invite people to come to visit us because of its natural attributes, and so you and I, [when] we want to turn left onto the highway, we’ve got to wait a while longer than we used to,” he says.

“We’re having fun, that’s why we live here. Resort guests are having fun, that’s why they come to visit. That’s why they come back—because they had a great time.”

When Keith’s petition began circulating last summer, several people wrote to council in support of commercial operations in parks, including Arts Whistler director Mo Douglas.

Arts Whistler had just hosted its first Art on the Lake event, which allowed guests and locals to bring their own kayak, canoe, paddleboard or boat to Alta Lake, or rent one from one of the local companies, to paddle around a “floating art exhibit” arranged at the south end of the lake.

“It’s a good example of bringing people to a really wonderful experience, using this remarkable environment that is the lake, but if there’s no commercial opportunity there to simply rent a kayak or canoe, that’s going to limit a lot of locals’ opportunities,” Douglas says, noting that many in the community can’t afford to purchase their own kayak or canoe, or may not have a car to transport it, or space to store it at home.

“Being able to access a few rental opportunities on any popular recreational lake in any community is a big asset, for both the residents and the visitors,” Douglas says.

“So for [Arts Whistler], we would hate to see that change and create a loss of a broader community opportunity that we happened to just create, recently.”

Dan Wilson, a resident of Alta Vista for 13 years (and a user of Lakeside Park for 25 years, including a stint working concession in the park in 1994), also wrote a letter in support of commercial operations.

“A concession has operated there for many years and this is not an additional use leading to park challenges,” Wilson wrote, adding that the concessionaire is a “guardian to the beach park in the summer,” picking up garbage, cleaning washrooms and reminding visitors and locals about bylaws.

“This duty could be enhanced if needed.”

The concerns would be better addressed through enhanced signage, extending bylaw enforcement from 4 p.m. to 11 p.m. in the summer, and better speed control systems for the Valley Trail, he wrote.

“Public access to waterfront is very important and shouldn’t be exclusive to those who can afford a multi-million-dollar lot on the lake—some of which destroy the shoreline habitat with landscaping to the water’s edge or with illegal floating docks and riparian area destruction,” Wilson said in a follow-up email, adding that with the RMOW working toward more access for the public and repairing the impact of landscaping and docks, “these goals should be supported.”

Making parks bigger is a benefit to locals and Whistler as a whole, Wilson added.

“Yes, it is busy at times, and that was to be expected when it became a ‘destination’ park. [But] the park was always busy in the past, only it was smaller so slightly less neighbourhood intrusion,” he wrote.

Further, commercial activity has been in the park “for at least 30 years,” and the current operators are great stewards.

“Certainly the river use itself should be managed better by both public and commercial users,” Wilson said.

“Arguably those in canoes with some training/education from the commercial operator are better managers of the area, however, than those local residents in tubes/rafts.”

‘The lakes are our gem’

Pressure on Whistler’s local lakes has been a growing concern in recent years, and a new group formed last summer aims to preserve and protect the resort’s summer jewels in collaboration with the RMOW.

The Whistler Lakes Conservation Association (WCLA) was formed last summer after the RMOW began work on a new dock strategy, said chair Michael Blaxland.

“Our No. 1 concern is the lakes, and protecting the environment of the lakes, so that involves water quality,” Blaxland says.

“We are concerned about the development around the lakes, so that would be parking and traffic and the issues that were raised by Lawrence … and we’re very interested in the whole issue of rogue party barges—docks and barges being generally too many, and too big, and not made of the right material, some of them.” (Read more at whistlerlakes.ca.)

Representatives of the group—which has close to 200 members (who are required to own lakefront property to join)—have met with the RMOW every few months to discuss pressing concerns.

Blaxland himself has been in the valley since 1979, and has lived lakeside at Alta Lake for about seven years.

“The lakes are our gem, and we have to preserve them,” he says. “And all but about maybe 20 days of the year, everything is OK, and then for 20 days of the year it gets blasted by too many people, too many issues, too much of everything, and it’s pretty chaotic.”

While Keith is a WLCA board member, the group has not yet taken a position on his petition, Blaxland says.

In his personal opinion, there are issues with sending users down the River of Golden Dreams (ROGD) in the later summer months, when water levels are lower, and concerns around inexperienced users renting watercraft and subsequently requiring rescue.

“So some of this stuff makes a lot of sense to me, but personally I recognize that there’s three groups that have an equal right to access to the lake, and use of the lake,” he said: lakeside owners, residents of Whistler who don’t live lakeside, and tourists.

A former guide himself, Blaxland sees the value in commercial operations in parks and on lakes.

“Tourists love it. It’s the highlight of their trip, to go on their first canoe ride and go down the ROGD,” he says.

“I think they have a right to use that, in my opinion, and we have to accommodate it. But all of us have to adjust, because it’s getting overused.”

The issues on Whistler’s lakes are complex, and constantly changing. When the RMOW took action on hauling out rogue party barges last year, for example, some took it upon themselves to simply build new, bigger barges.

“That type of stuff has got to stop,” Blaxland says.

“The issues are complex, and we just have to work through them.”

For Keith, the issue is simple: the municipality needs to adhere to its own zoning.

“I think if they kept to the zoning, it wouldn’t be so overcrowded, and the problem is they haven’t complied to their zoning,” he says.

Increasing the park itself is good, he adds, because “the people can enjoy the park—but this commercial component has grown out of control,” he says.

“[But] putting commercial in the middle of a residential area just introduces conflict, because there’s opposing wants and needs.”