In October 2020, Peacemaker Azuegbulam was serving in the Nigerian army, engaged in combat against terrorist forces in northeast Nigeria. He was 24 years old.

The region has grappled with Islamist militant conflicts for more than a decade, and perhaps most notoriously with Islamist, jihadist terrorist organization Boko Haram—the forces Azuegbulam’s military unit were embroiled with four years ago.

Then Azuegbulam’s life changed forever.

His unit came under fire from Boko Haram in the northern part of the province, gravely injuring many—Azuegbulam among them.

The brutal attack resulted in a “very painful amputation” of Azuegbulam’s left leg, and left the Nigerian traumatized.

“After I got injured, life was very miserable to me … it was very tough on me,” Azuegbulam says.

“I was emotional ... I was very angry.”

Rather than dwell on the pain, Azuegbulam focused on recovery—and just three years after losing his leg, made his debut at the Invictus Games.

Competing for the first time in Dusseldorf, Germany, in 2023, Azuegbulam made history when he became the first Nigerian (and African) Invictus Games champion, taking gold in powerlifting.

Azuegbulam was in Whistler last month for the Invictus Games Participating Nations Training Camp, marking one year out from the Games themselves, to be hosted by Whistler and Vancouver in February 2025. He was one of 60 competitors, coaches and managers from 19 countries taking part.

He was one of several athletes who spoke about how the Games have helped in their recovery.

“I feel good, I feel loved to be champion No. 1 [in] Africa, because the first time I got injured, I was like, nobody cares about me, and nobody loves me,” he says.

“But when I won, I see that, yes, people really love me, and also, I feel good. I feel recovered.”

ONE YEAR OUT

Stories like Azuegbulam’s are at the heart of the Invictus Games mission.

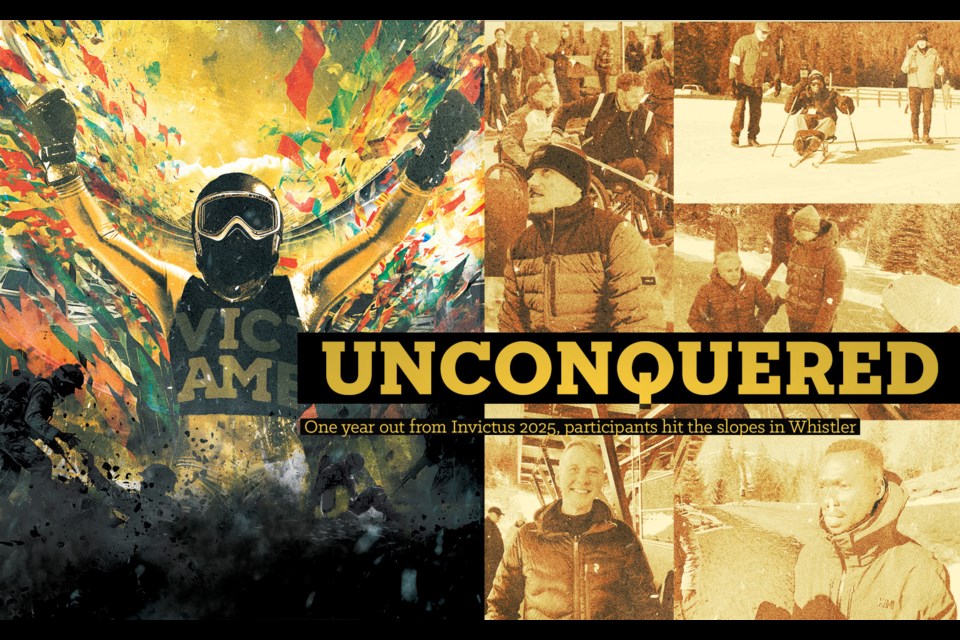

Founded in 2014 by Prince Harry, the Duke of Sussex, Invictus—in Latin, “unconquered”—is an international, multi-sport competition for wounded, injured, and sick servicemen and women.

The 2025 edition will mark the seventh Invictus Games in its history, and the first time it includes winter sports.

“The decision to include winter adaptive sports in the Games aims to help Participating Nations build year-round adaptive sports programs, and the competitors welcomed the new challenge at Training Camp and demonstrated once again the power of sport to support rehabilitation and inspire recovery,” says Scott Moore, CEO of Invictus Games Vancouver Whistler 2025.

During their time in Whistler, athletes were able to test out winter sports like adaptative skiing, skeleton, and wheelchair curling for the first time.

Azuegbulam was in the thick of it, hitting the slopes to try adaptive skiing on Feb. 14 and rocketing down the track at the Whistler Sliding Centre on a skeleton sled on Feb. 15.

While he didn’t much like the cold, Azuegbulam says he enjoyed the opportunity to participate and try new sports.

“I see myself participating, always,” he says. “The Games really helps me in my recovery, mentally, emotionally.”

With the camp behind them, organizers now have their sights set on the main event, taking place from Feb. 8 to 16, 2025.

“We’re now looking ahead to next year, where you can expect to see alpine skiing and snowboarding, biathlon, Nordic skiing, skeleton, and wheelchair curling included in our first-ever winter hybrid Games,” Moore says.

Those looking to get involved can visit invictusgames2025.ca, and either register to volunteer, sign up for the Games’ newsletter, contribute to its charitable arm, or sign up for event tickets.

‘IT’S AWESOME HERE’

But there’s a whole lot of prep that has to take place before athletes can compete in 2025.

As chef de mission of Team Netherlands, Stefan Nommensen—a professional serviceman and former Invictus participant himself—is in charge of the entire Dutch squad.

It’s a tall task, but “that’s why we have a staff; we have specific trainers for the different sports,” he says.

“We hope by June that we have selected the team, so that we can go really into the team sports and into making decisions on what sports everyone is going to do here.”

Nommensen took part in the 2018 Invictus Games in Sydney, where he competed in road cycling, swimming, sitting volleyball and athletics.

“For me, it was the experience of all the sports and all the people … it’s meditative, it’s part of their rehabilitation,” he says.

The upcoming Games in Whistler will be an adjustment for many participants, who are taking part in snow sports for the first time. Nommensen lauded the work of the trainers during the Participating Nations camp, pointing to Azuegbulam as an example.

“He has been in the classes, and it’s amazing how the adaptive-sports trainers are able to teach and train and make him comfortable in the snow,” he says.

“And imagine that, the Netherlands is almost about three-quarters below sea-level; we don’t have any mountains, and a lot of us, particularly those with impairments, haven’t been exposed to winter sports … so we are really, really happy [with how training camp has gone].

“It’s awesome here.”

For many participants, Invictus is as much about the camaraderie and the social aspect—a chance to meet and bond with those who’ve experienced similar to you—as it is the sport.

Rasmus Penno is a bilateral leg amputee from Estonia. Like Nommensen, he took part in Invictus 2018 in Sydney, where he competed in indoor rowing.

Penno was injured in 2008 while on a mission in Afghanistan. He spent a year in a rehab centre in England recovering, where he made lasting connections.

“I made a lot of good friends in England, so I hope to meet them in 2025,” he says.

“I know that one of them is doing mountain skiing. I’m not sure if he’s coming next year … we’ll see.”

During his time in Whistler, Penno got to try out skeleton, and both alpine and Nordic skiing, but winter sports aren’t completely new to the Estonian.

“We don’t have mountains, so we do more the cross-country skiing. We have like an adventure park where you can do the mountain skiing, but there, it takes more time to get up than slide down,” he says, adding he enjoyed trying out new sports ahead of the 2025 Games.

“Mountain ski, that was fun—the muscles, still hurting.”

PERSONAL VICTORIES

Giorgio Giuseppe Porpiglia, a marshall in the Italian navy for 20 years, feels right at home in the mountains.

“He was an athlete before the accident, and when he knew the opportunity came to participate in the Invictus Games, he was glad to do this and he is glad now to be here,” Porpiglia says, through a translator.

“It’s a dream that has come true. Sports has helped him to reach other things that he has not thought to reach before. Not for the victory, but for himself.”

As the translator says the last line, Porpiglia pats his chest proudly.

A manual wheelchair user, Porpiglia was part of a group of 16 athletes from the Paralympic Defense Sports Group who swam across the Strait of Messina in Italy in 2022.

Porpiglia took part in the 2023 Invictus Games in Dusseldorf, where he participated in wheelchair sports and table tennis—but the Whistler Games in 2025 represent something more.

“This is my sport,” he says of alpine skiing, gesturing to the mountains around him with a big, beaming smile.

“The others, I just participate … and now, next year, I am competitor in my sport. I do this sport 18 years.”

The Participating Nations Camp was Porpiglia’s first visit to Whistler—he almost came for the 2010 Olympics with some friends, he says, but didn’t make it out.

Is he excited to finally ski one of the best resorts in the world?

“Yes. Fantastica. Yes, yes, yes,” he says, beaming again. “Absolutely.”

‘ANOTHER EPIC WEEK’

A veteran himself, Prince Harry was inspired to found the Invictus Games after returning from deployment in Afghanistan.

According to the Invictus Games website, the Duke of Sussex was moved to act after he saw the coffin of a Danish soldier loaded for repatriation, alongside three injured British soldiers.

“That moment had a profound impact on him and, following a visit to the US Warrior Games in 2013, he was inspired to create the international Invictus Games to celebrate the unconquered human spirit, and shine a spotlight on these men and women who served,” the website reads.

Prince Harry and Meghan Markle, the Duchess of Sussex, visited the Participating Nations camp in Whistler and Vancouver, where they spoke with participants—and Prince Harry tried his hand at the sports himself.

“Invictus is not necessarily about winning a medal, but about the bonds that are built between nations; about the shared journey of recovery that competitors and their families are a part of,” Prince Harry said at a dinner in Vancouver on Feb. 16, wrapping up the event.

“Tonight, we take one big step on that journey, and in less than 365 days, we welcome the world to join us once again for another epic week.”

The Duke singled out Azuegbulam in his remarks, saying the Nigerian veteran would have stayed on Whistler’s slopes if he could.

“But these last few days have been very, very special, because it’s been our first opportunity to have some friends, some family and come competitors here with the coaches,” he said. “[And] as well to be able to try out, in some instances, for the first time being on snow.”

The Invictus Games Vancouver Whistler 2025 will bring together more than 500 competitors from more than 20 nations from Feb. 8 to 16, 2025.

Read more and get involved at invictusgames2025.ca and invictusgamesfoundation.org.