[pullquote-1] That was the opener from Alden Meyer in a New York Times article leading up to the largely failed climate conference in Madrid this past December. Strategy chief at the Union of Concerned Scientists and an expert on climate policy and the Paris Agreement, he was commenting on the UN's dire "emissions gap" report released right before the conference. Not only have we (all of us) failed to cut greenhouse-gas emissions—we've actually increased them.

"... And (we) need to wake up and take urgent action," was how Meyer finished his sentence.

Evidence everywhere backs up scientists' warnings that a point-of-no-return disaster is looming: The highest January global temperatures were recorded this year, the hottest January since the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration started keeping records 141 years ago. Brush fires in Australia so big they couldn't be fought. Zambia's famous Victoria Falls shrunk to a trickle by drought. Temperatures reaching almost 30C near the Arctic Ocean last spring, as atmospheric CO2 in 2019 hit its highest levels in human history.

Santa Barbara, where Earth Day originated, has warmed 2.3C since the late 1800s, and it's so hot in Qatar they air condition outdoor spaces like shopping districts and Doha's 40,000-seat stadium—burning more fossil fuels and generating more CO2 to do so.

Urgent action? Huh.

As for waking up, some are. And Switzerland, known as the "water tower of Europe," may be among the most "woke," for good reason.

Riding the trend of melting glaciers that's impacting the whole world—including right here in B.C. along with the Antarctic and its Thwaites Glacier, which could raise sea levels by half a metre alone if it melts—more than 500 Swiss glaciers have already disappeared since 1860, and 90 per cent of the remainder will be gone by the end of this century if emissions aren't cut. Those are glaciers that supply critical fresh water to much of Europe.

Centuries of ingenuity and education have made the Swiss masters of innovation and precision, especially in clean tech.

The University of Basel, founded before Christopher Columbus sailed the ocean blue, is known for its outstanding research and technology transfer. Since the 1800s, ETH Zurich, a world leader in science and technology, has graduated 20 Nobel Prize laureates, including Albert Einstein. Lausanne's big polytech campus, the Swiss Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL), founded in 1855, is one of Europe's most vibrant science and technology institutions. To top things off, the not-for-profit Swiss Centre for Electronics and Microtechnology (CSEM)—now a leader in those fields along with photovoltaics (the conversion of light into electricity)—was created to push things beyond watchmaking. (Ironically, my main source for this article, whom you'll meet in a minute, sports a watch powered by a solar cell smaller than a penny.)

Not bad for a nation of 8.5. million people, about the same population as Quebec's.

Eco-warriors we need.

The Swiss are champion recyclers and green advocates. Their recycling rate for municipal waste is over 50 per cent. They've been fascinated with alternative energy technologies for decades, and recently voted in a new energy plan that emphasizes renewables and hydro. Although they use primarily low-carbon sources now—over half their power comes from hydro and one third from nuclear—the new plan aims at getting off nuclear and onto renewables like solar.

More importantly for the rest of us, they've been huge innovators in photovoltaic (PV) solar energy, which just might be the ticket to answer that call to action and snap us out of our sleepwalk.

The International Renewable Energy Agency, based in Germany, reports that solar PV, if deployed effectively, could deliver one fifth of the CO2 emission reductions needed by 2050 to prevent catastrophic warming.

"The earlier the better for the planet," he adds.

There's also the big economic argument. Even though Switzerland is not especially sunny, every square metre of land gets between 1,000 and 1,500 kWh a year from the sun, about the same as Whistler and Vancouver. That's the energy equivalent of a barrel of oil per square metre. In terms of energy costs, it's much cheaper for a country like Switzerland to import solar panels than oil, by a factor of 15 or more.

"So it's a no brainer—countries that can get rid of oil quickly will be much richer in the long term," Ballif says.

"For the same cost as two years' worth of fossil fuel imports here in Switzerland, we could have PV solar panels which would produce the same amount of useful energy, but they would provide electrical power for 30 years, not just two."

Switzerland was a pioneer in solar PV, but lost its edge in the 1990s when support, such as installation incentives, was cut back. And while they don't manufacture PV solar cells (China has taken that lead from Europe), they assemble them into panels. Still, Swiss solar technology is virtually everywhere.

"If you buy a piece of PV technology, you can be sure it has some Swiss technology," Ballif told journalists when we visited the CSEM centre. "It was capped with some Swiss equipment; it was coated with some Swiss finish; it was measured with Swiss metrology; it has been calculated with Swiss software, because of the innovation level of Switzerland."

In Switzerland itself, solar is cheaper, more efficient, more popular and more innovative than ever. For instance, they've figured out how to slice the silicon wafers used in PV solar cells to one fifth of their former thickness, saving materials, but also making them much more flexible—perfect for use on curved surfaces like airplane wings.

As well, REC Solar—the largest brand of solar panels made in Singapore—is developing one of the best 60-cell PV panels on the market using Swiss technology, improving on big REC panels currently used in large-scale applications like the Dubai Airport (15,000 solar panels, although the Indianapolis airport boasts more than 87,000!) and Audi's production plant in Brussels.

Other game-changers include solar innovations that architects and builders anywhere in the world would love.

"In Switzerland, we have a sensitivity to buildings' aesthetics," says Ballif, showing journalists an image of a typical Swiss cow with a shiny, black, rectangular solar panel draped on its side, then the same cow with a fully integrated panel in terms of colour and shape that blends in so well you can barely see it.

Ergo the many Swiss advances in taking building-integrated PV (photovoltaic materials used to replace conventional building materials) to new levels of architectural integrity.

Probably the biggest innovation architects and building owners are welcoming are white solar panels CSEM has developed—perfect for vertical walls, which are usually white or light-coloured. The technique is hush-hush, but these white PV panels have a surprisingly high efficiency of about 12 or 13 per cent. (Black panels—understandably the preferred colour for its superior ability to absorb solar radiation—have an efficiency of about 19 per cent, which is constantly increasing.)

Another solar game-changer are bifacial solar cells, which catch light from both sides. Developed at CSEM, they're already being used on buildings in Sicily, Singapore and Russia. This is a big new trend, according to Ballif, because when the solar panel is installed at the right angle it also uses light from the back, generating 20 per cent more energy for the same price.

"That would really make a difference to energy production," says top Whistler builder, Bob Deeks, president/owner of RDC Fine Homes and a Canadian trailblazer in sustainable housing.

Then there are the small solar roof panels about the size of a shingle—perfect for edging a hip roof, and retractable solar panels based on coverings for mountain cable cars.

Another popular innovation used on hundreds of Swiss buildings—something you can't help but notice on CSEM's Neuchâtel headquarters—are huge, beautiful, eye-catching solar screens developed with new technology, such as multi-wire interconnection. The CSEM's 600-square-metre facade generates 60,000 kWh a year, enough to meet 12 families' power needs.

"The light hits between the solar cells, reflects off the shiny wall, and gets collected at the back of the modules. All the electricity is fed back to the local utility grid, which sponsored the project," says Ballif.

Micro-solar panels, flexible solar panels. A solar project on Lac des Toules in Switzerland that could power over 6,000 households. Coloured solar panels, illuminated panels, two-sided ones—all of these are effective solar energy innovations we can only hope the world will wake up to and use more urgently.

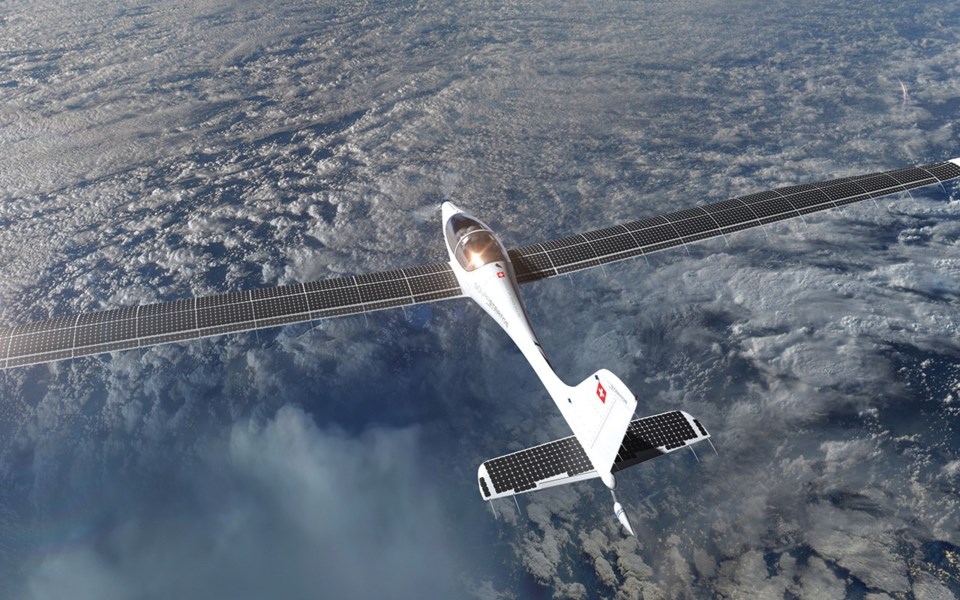

But possibly the most intriguing piece of Swiss solar ingenuity are the thin, lightweight PV panels that powered the first solar aircraft around the world and will soon carry another one to the edge of space.

SELF-SERVING ILLUMINATED ART

Why is it important for a museum to use innovative, non-carbon technology?

"Well, as archaeologists also working on the evolution of climate since prehistoric times, we are particularly aware (and worried) about the problem of climate change," writes Marc-Antoine Kaeser, the director of Laténium, via email. "As a museum director, I am happy to contribute to saving energy, because ... the museum is a big energy consumer."

To the edge of space—powered by the sun

In 2015, many excitedly followed the flight of the huge, graceful Solar Impulse, which is based at the Payerne Airport near CSEM's headquarters. Piloted by Bertrand Piccard (no, not that Captain Picard), it was the first aircraft to fly around the world using solar power—welcome news for an industry whose CO2 emissions have been vastly under-estimated. The contrails generated off airplanes' wingtips are even worse for warming.

There must be something in Swiss water that inspires so many "firsts" in solar-powered adventures: They made the first solar-powered race car and the first solar-powered racing boat, and now they're taking flight to the next level of solar transport.

A stone's throw from the Solar Impulse's hangar—where the Swiss air force was practicing loud manoeuvres overhead on the blistering July day we visited—is the home of another solar aircraft, the SolarStratos. This plane is the brainchild of pilot and explorer, Raphaël Domjan, who first got serious about solar power after he witnessed the disappearance of Iceland's Myrdalsjokull Glacier.

The power source? More than 20 m2 of thin, lightweight, slightly curved solar panels with an efficiency of more than 24 per cent and made with CSEM's help. Durability is also key. The panels, which are mounted on the wings that span 25 m., can resist UV light and huge thermal cycles.

In the meantime, Domjan, who also headed the PlanetSolar project—the first solar-electric boat that circumnavigated the world—plans to break another world record for a solar aircraft this year. He'll pilot the SolarStratos to 10,000 m., double the old record.

All these solar projects are adventures, yes, but their purpose is far more critical: Proving solar power is viable.

"The main goal is to change the perspective of younger generations. In the world of today, they think they will not be able to take a plane or to travel anymore via car. We face a problem, of course, a climate emergency, but we have the technologies to change so we don't have to think that we have to go back to the cave," says Domjan by phone from his chalet in the Val d'Anniviers.

Already, a company is interested in using the technology to make commercial two-seater aircraft that won't go into the stratosphere, but might take us from Vancouver to Kelowna.

Stand by...