This story contains content and themes that may be upsetting to some readers.

The lifeblood of any community is its children—the future. Earlier this month, the youngest members in the Sea to Sky corridor got ready for their first day of school. They posed for photos outside their front doors with eager smiles and freshly ironed uniforms. Most parents could not even imagine these blessings being ripped away from them for even a day.

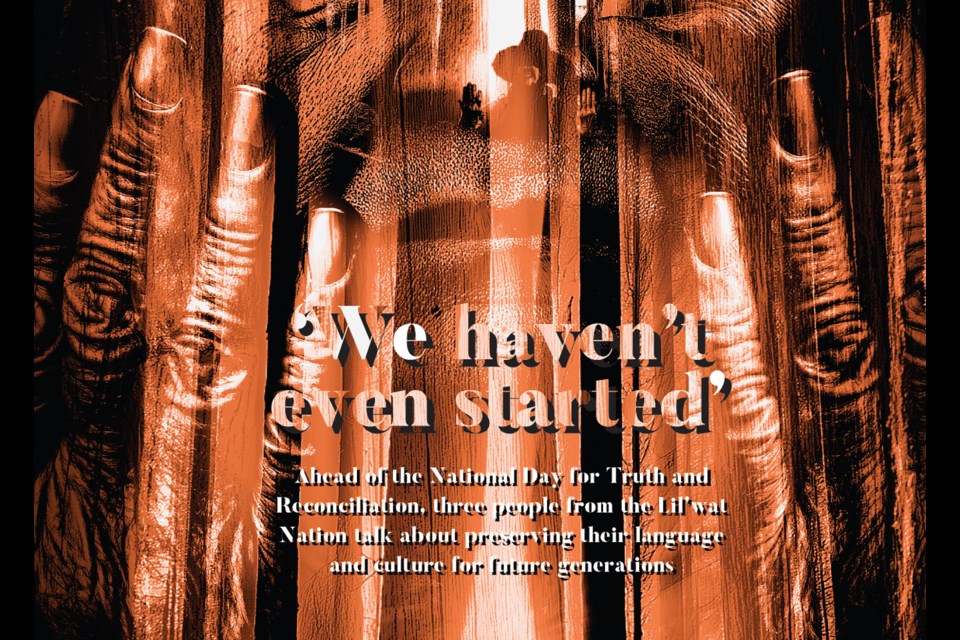

Today, people in the Lil’wat Nation celebrate the culture their ancestors fought so hard to save. Canada’s historical residential school system threatened to stamp out their language, their songs and their way of life. It cast their infinite wisdom aside and called them stupid.

Through the residential school system, Canada took Indigenous children away from the families that loved them. It broke their spirit and tortured them in ways that go against the very meaning of humanity. It turned bustling communities into ghost towns and schools into places of horror. But hope perseveres.

Ahead of the fourth National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, Pique spoke to three inspiring members of the Lil’wat Nation about their efforts to celebrate their land and customs in a world where being different no longer means being less-than.

Education

Dr. Lorna Wanosts’a7 Williams is Professor Emerita of Indigenous Education, Curriculum and Instruction at the University of Victoria and Canada Research Chair in Education and Linguistics. She has spent her life ensuring Indigenous children get the start in life they deserve—a start stolen from Wanosts’a7.

“The main battleground for the rights of Indigenous people was really education,” says Wanosts’a7. “This whole push for reconciliation is because Canada, like other colonizing countries, sought to silence the languages and knowledge of Indigenous people.”

She explained the remoteness of Mount Currie served as a blessing when it came to protecting a language spoken since time immemorial.

“We were really fortunate in Mount Currie that it was tough to get there,” she says. “We were able to maintain our language longer than many other communities. But because of residential schools and other polices of their government, we did see a real rapid decline of language. We also saw a decline in our relationship with our land. The governments and capitalism devastated the forests and everything that grows there.”

Before being sent to St. Joseph’s Mission near Williams Lake, and the St. Joseph’s Indian Residential School that operated there from 1891 to 1981, Wanosts’a7 went to day school in Mount Currie.

“I could see what they were doing to us,” she says. “Before we were going to the public school in Pemberton, they brought psychologists in to test us. Most of the people in the class, 45 of us, were designated to be ‘retarded.’ I was one of that group. At the time we found out, we were laughing at it because we knew we weren’t. But that’s how we were designated. They used those tests to put us into modified classes in public school. That’s what was happening to our people.”

The group of friends joked about the label, knowing even at their young age it was a lie. However, the designation lingered in Wanosts’a7’s head for decades.

“We laughed it off, but it was something that hung over me,” she says. “I questioned my capacity and ability. I didn’t have an understanding of a difference of cultures. The way that we speak is different from the English world. The way that we organize our information and our knowledge is different from the English world. In the English world, when people are different it means less-than. It becomes devalued.”

But Wanosts’a7’s first introduction to education was a pleasant one. Her brothers were ahead of in her school and helped her to learn a few English words.

“I started school in Mount Currie,” she says. “In our family, we only spoke our language. I remember them trying to teach me some English before I got to school. They taught me ‘yes,’ ‘no,’ and ‘maybe.’ We had a really good teacher and I learned a lot of English that year.”

Then, at just six years old, she was taken from her loving family and sent to residential school—were she completely lost what she had learned.

“In a very short space of time, I lost all capacity for communication,” she says. “I couldn’t use any language.”

When little Wanosts’a7 came home, her spirit was broken.

“I was so confused, and I didn’t know what the heck was going on,” she says.

Wanosts’a7’s physical health was also cause for concern. She recalls ending up in the hospital for four months when she came home from residential school.

“I learned English during those months. Then, the older people in the community helped me to regain my own language,” she says. “That was so key to who I am today. At a very young age, I was bilingual even though I didn’t know what that meant at the time.”

The helpful kid would volunteer her services as a translator, even though she didn’t know it at the time. “If the old people needed to go to the Indian agent, to the store or the doctor, they would take me with them,” she says. “I could translate. At the time, I didn’t know that was what I was doing for them.”

In 1973, Wanosts’a7 was instrumental in opening Mount Currie’s band-controlled school, the second First Nation in Canada to do so.

“It was a concerted effort by lots of people in the community,” she says. “We knew we had to try to change it. One of my sisters was the only teacher in Mount Currie. Her name was Mary Louise Williams. She worked with the Union of Indian BC Chiefs at the time to advocate for our rights. It was through the work of the union and the National Indian Brotherhood, which became the Assembly of First Nations. They put together a case.”

The people of the Lil’wat Nation finally got a chance to say what they wanted their children to learn, and Wanosts’a7 recalls visiting every household to talk to every family about what they wanted for their children.

“That’s what guided our school that exists now in Mount Currie. The people said that they wanted the school to focus on the retention of our language, for the children to learn how to speak our language. They wanted their children to learn our history,” she says. “At that time, what existed in the school curriculum about us was either zero or it was to help Canada become a country. It was also that we were poor and not able to look after ourselves.”

Parents wanted their children to learn what Canada had done to them. “At that time we weren’t using words like ‘colonization.’ That’s what they meant,” Wanosts’a7 says. “They wanted their children to learn the effects of what happened to us with the imposition of Canadian laws. They took away our languages and made us fight for our rights.”

However, families stressed that their children had to learn how to live in two worlds.

“They have to be able to live in our world, and they have to be able to live in the white man’s world,” Wanosts’a7 says. “At that time, it was pretty insightful.”

Some were afraid to practise their culture and speak their language—a sentiment that hasn’t fully vanished.

“There are some who still have those thoughts and feelings,” Wanosts’a7 says. “People wanted the best for their children. They were being told that our languages were a detriment for people. We were told that we would never be able to make it in the world if we spoke our language.”

Wanosts’a7 says people still struggle to understand the importance and depth of First Nations languages and knowledge systems. In March, she was invited by Pope Francis to speak in the Vatican Apostolic Palace as part of the Meeting on Indigenous Peoples, organized by the Pontifical Academies of Sciences and Social Sciences.

“He believes that Indigenous knowledge will help the world deal with the damage that humans have done to the Earth,” she says. “This was big. He invited 50 Indigenous people from across the world to have this discussion for two full days. They are still working on the report.”

The road to reconciliation is long, but Wanosts’a7 is hopeful.

“I can see the changes that we are able to make,” she says. “Just being asked about reconciliation is a big step. It’s something that Canadians are struggling with and having conversations about. Sometimes, they aren’t good, but at least there are conversations. The only way that we are going to be able to reconcile is if we can talk with one another, share and not be silenced.”

She watches proudly as the next generation of Lil’wat take the baton.

“It makes me happy when I see young people using the drum and singing our songs,” she says. “Knowing that finally people in Whistler and Pemberton are wanting to know our history is important. There is so much work that needs to be done, to document and safeguard our languages. I see people who are working on this, studying, learning and exploring. It comforts me that the work will continue.”

Wanosts’a7 had simple advice when asked what Canadians can do during this era of important change.

“To want to know and not to be afraid to ask, even if they ask in the wrong way,” she says. “Our people have always been very generous and accommodating. They will continue to be.”

Art

Twenty-one years ago, Lenny Martin Andrew, the son of former Lil’wat Nation Chief, Leonard Andrew, began carving. What started as a way to put food on the table became a lifelong passion that would capture people’s hearts around the world.

Andrew was going to college in Squamish, he recalls—a starving student who needed money.

“I had these carving poles that I had bought a long time ago,” he says. “The first thing that I ever carved was a rattle. I brought it to the local gallery. I sold it for $300. That’s how it all started. I created my own style, my own art form.”

Along the way, Andrew realized the importance of his work and the legacy it will leave behind.

“It gives us identity—who we are and where we come from,” he says.

He started small with plaques, then moved on to masks. A decade ago, he had the opportunity to study with master carver Rick Harry.

“He is what I would consider a grandmaster carver,” Andrew says. “He has done it all.”

The market for his work has opened up in the last five years, as the conversation about reconciliation in Canada has gained steam. Andrew says he doesn’t even really have to advertise anymore.

“I let my work speak for itself. I always felt a little bit shy about marketing my work. I decided just to make it super beautiful, and that works,” he says. “I have collectors. I never get to finish my work before it’s sold. I show pictures on Facebook. I sometimes get three people at the same time looking to buy it. Whoever hits me up first, gets it.”

It wasn’t always like this. Andrew recalls being a “starving artist,” adding he had to earn the recognition he has today.

“I like to challenge myself with every piece I make. I like to make it more extreme than the last one,” he says. “My work has evolved over the years, like me.”

In recent years, Andrew has taken on the role of teacher, in the hopes of passing the art form into the safe hands of the next generation.

“There has always been someone younger than me beside me, interested and willing to learn,” he says. “It’s fun. I enjoy teaching and showing.”

Music

Russell Wallace is an award-winning composer from St’at’imc and Lil’wat Nation who shares the songs his country once tried to steal from his mom. When Flora Wallace attended residential school in Kamloops in the 1930’s, she was beaten by nuns for singing in her own language. That didn’t stop her. Now her son passes her stories on to “anyone who will listen.”

“She was beaten for speaking the language or singing the language, but she was determined to keep it going,” says Wallace of his musically gifted mother. “She could pick up a melody and remember it and sing it back to you. Even before speaking English, you would learn songs from the gramophone. She didn’t speak English at that point, but she was singing country songs. I think that comes from the oral tradition as well.”

Flora got scarlet fever while in residential school. The adults there left her to die.

“A number of children died from it,” says her son. “She was there to witness it. They put them in a room, like a cold room, and it had a dirt floor. All they did was put beds in there and put a bucket of water in the middle. Every day, she crawled to that bucket of water and made sure she was hydrated. She knew she had to keep drinking, so that’s what she did.”

The little girl heard the other children’s cries slowly disappear. She knew, even at her young age, that she would never hear them again. For a long time, nobody would believe Flora Wallace’s story. They couldn’t believe a human would do that to defenceless children.

“The lawyers didn’t believe her,” says Wallace. “They said that no person would kill a child and bury them in the schoolyard. They were kind of gaslighting her, saying that it didn’t happen.”

Flora eventually met the love of her life and moved to Mount Currie, where she was determined to learn as much as she could about her culture—including the songs she was so instrumental in carrying forward for future generations.

The strong-willed, no-nonsense lady always sang at the top of her lungs while doing housework. She taught her children bits and pieces of their language when they asked, determined to pass it on.

Flora’s dying wish was that future generations would share the songs some tried to stomp out forever.

“Before she passed away, she told me to keep sharing these songs and not to let anyone to stop me from sharing them,” Wallace says. “So many people had tried to stop her from sharing them. My responsibility is to keep sharing them out of respect for her. I share them with anyone who wants to learn.”

He explains his role as a teacher is incredibly important. Wallace spends a lot of his time working with youth in universities and helping disadvantaged teens get the start they need. Hearing his own songs sang back to him never gets old. He is currently teaching refugees all about his First Nations history through a Vancouver Youth Choir project called Kindred.

“A big part of why I am an artist is to teach,” he says. “As an artist, I have a responsibility to express myself and create new works. But in the end, I have a responsibility to share these songs and the language that my mom taught me. I don’t have all the language, but I pass on the little words I learned from her.”

Trailblazing Flora had 11 children, and was always thinking about keeping them fed and healthy. She also ensured they had food stored in the house, food that couldn’t be taken away.

“Every day she would say, this is what the church did to me,” says Wallace. “This is what the government of Canada did to me. She talked about growing your own food and eating your own food. It was important to ensure that everyone around you is fed. It was because they were basically starved in school.”

That’s not to say there was a shortage of food in Canada at the time.

“There was plenty of food,” says Wallace. “A lot of the food was sold or whatever to make money for the church. If someone high up in the church came to visit, they were given the best food. The children were the ones who were starved. Their food was basically gruel. They boiled potatoes without peeling them and just mashed them. She remembered eating this really horrible porridge and finding mouse droppings in there. They were so hungry that they just ate whatever they were given.”

Russell believes the path towards truth and reconciliation is only beginning.

“I think Canada has a long way to go,” he says. “I feel like we haven’t even started. We have people who are denying that residential schools were that bad. We have people denying that there were bodies under their schools. How can we move forward when people don’t even believe us?”

Canada’s National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, held Sept. 30 each year, marks an important step in moving forward.

In Whistler, admission to the Squamish Lil’wat Cultural Centre is free on Sept. 30. Read more about the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation at slcc.ca/ntdr.