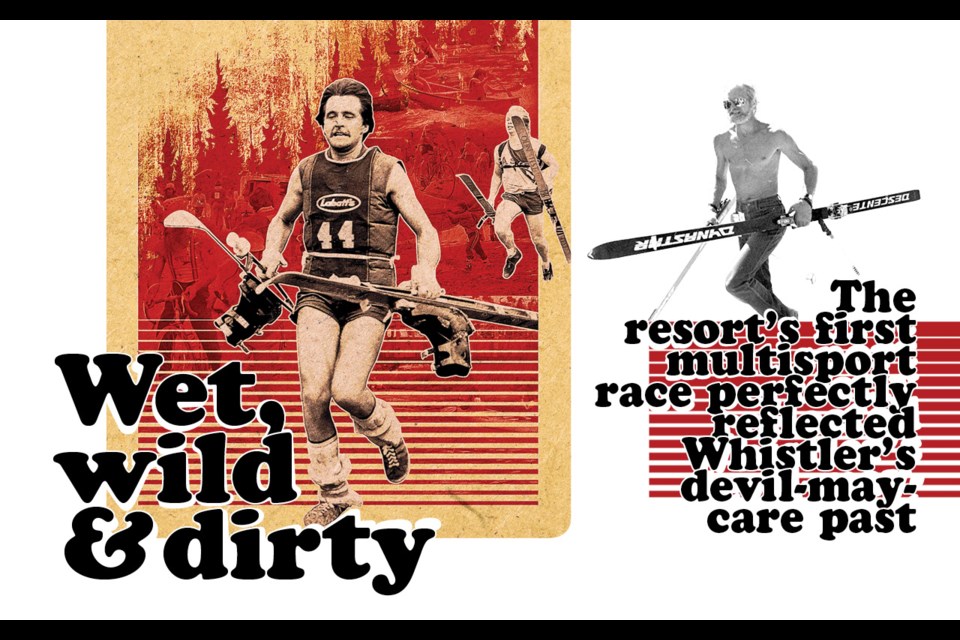

It’s May 25, 1975, and high up on Whistler Mountain, a shotgun blast rings out, followed by a frenzy of 25 people racing on foot to where their skis lay in wait. Their goal? To be the first to make it down the slopes. Thus began the first ever Great Snow Earth Water Race in Whistler. Little did anyone know at the time, but the multisport relay race—which features downhill skiing, cycling, canoeing and running—would become a cherished annual event, spanning 16 years. Nearly half a century since its inception and it still holds a special place in the collective memory of many Whistlerites.

And it all started as an idea that came to Bryan Walhovd in his sleep one weekend, as a way to get his various athlete friends involved.

“I just woke up one morning after thinking about it all night and talked to a few friends and we said, ‘Let’s see what we can make happen.’ And we chose the Sunday of the long weekend in May,” he recalls. “And that was the formation of the Snow Earth Water Race.”

At the time, Whistler was still months away from being established as Canada’s first resort municipality, and with no village yet, and not much established infrastructure, the town was still very much off the beaten path—and the inaugural race reflected that.

With very few rules and regulations, both Whistler and the Great Snow Earth Water Race of the time were wild and untamed, filled with outdoorsy people who foresaw what Whistler would eventually become: a true four-season resort.

“I think there was a kind of youthfulness to Whistler at that time,” says Brad Nichols, executive director of the Whistler Museum, which hosted a speaker series event in May looking back at the race. “Everyone that was here was kind of putting themselves behind what Whistler would become. It was like a dream, and a lot of people believed in the town.”

With that kind of energy behind it, it wasn’t shocking that the race quickly became the unofficial kickoff to the summer season. The first year included 25 teams, all of which were ready to do whatever needed to be done to win the grand prize of… bragging rights and a T-shirt.

“I think most people are quite competitive, whether they’re competing against themselves or competing against their neighbour running down the hill,” says Walhovd.

“And I think it was just a lot of likeminded people. We all really loved skiing—fanatics, I guess you’d call [us]. There was a commonality of interests in all of us. There’s climbers, there’s hikers, canoeists, bicycling had just really started to take off. I think it was just another thing to do to.”

With its no-holds barred approach, that inaugural race featured only one real rule: competitors had to get to the bottom of the mountain with all their equipment. Naturally, with more than 100 highly competitive racers, there were quite a few stories of the shenanigans that went on after the race had concluded.

One savvy team reportedly coordinated with the gondola operator to take them down the mountain only to get stuck halfway and find out another team had bribed the operator to stop the lift. It even went so far as people stealing other teams’ rides down the mountain, according to Walhovd.

“The other incident was that somebody had taken a motorbike up, and this guy comes screaming down and says, ‘Yeah, I substituted with your buddy, I’m the skier now. Take me to the bottom,” he says, reminiscing on the race’s first year.

“So, the guy took him down to the bottom and he said, ‘You better go up and get your team member; I wasn’t on your team.’”

For the first 16 years of the race’s existence, the Great Snow Earth Water Race captured the spirit of Whistler. And as the resort grew and changed, so too did the race. The number of competing teams rose steadily every year, and in 1983 a new sport—cross-country skiing—was added, bringing the total number of events to five, and increasing each team from five to seven members.

By the end of the ‘80s, both Whistler and the race had more than doubled in size.

“I think if you look at 1980 when the village was coming to completion, until the end of the decade … [Whistler] went from a regional market to, starting I think around ‘91, ‘92, being voted the No. 1 ski destination in the world,” says Nichols.

“So really, that 10-year growth period was exponential, and it just changed radically how the town was perceived and how the town operated.”

By 1988, the Great Snow Earth Water Race had over 200 teams, 1,400 participants and attracted major media attention that even included an entire Japanese film crew that followed a team from Japan that had entered that year.

Sadly, the race’s growing popularity would also mark the beginning of the end of its original incarnation. More people meant more organization and planning for Walhovd and his committee and eventually it just got to be too much to handle.

“It’s too bad it couldn’t have carried on a few more years, but I maxed out about that time. We had television, not only from Japan, but we had local television and radio coming up,” remembers Walhovd. “Especially during the final registration on the Friday, there were people asking me questions and I was trying to get all the people organizing the registration going, and I almost blew my cork because I just couldn’t handle it all.”

While the end of the Great Snow Earth Water Race might have been foreseeable, it wasn’t inevitable. The proof of that lies just below the border, in Bellingham, Wash., where a similar multi-event race has been held since 1973.

With so many similarities between the races, looking at what Bellingham’s Ski to Sea Race has become is like looking through a window into an alternate universe where the Great Snow Earth Water Race had never been scrapped, but instead, continued growing through the ‘90s and into the 21st century.

Both races started in the mid-‘70s, and both began with modest registration numbers before growing substantially year over year. Whistler’s race reached a peak of 1,400 participants in the late 1980s, while Bellingham’s, currently, can reach upwards of 4,000 competitors per year.

The Great Snow Earth Water Race started with four events; Ski to Sea with three. Both added cross-country skiing after a few years of operation, and today, Bellingham’s race consists of seven different events.

However, the one glaring difference between the two races is how they were handled when coordinating them got to be too much.

In 2011, a committee was formed with the sole focus of continuing the uber-popular Ski to Sea Race after the its original organizers, the Bellingham Chamber of Commerce, decided it had grown too large for them to take on.

According to Anna Rankin, Ski to Sea Race director, the key to keeping an event like this going for as long as they have, is momentum, consistency and having people who are passionate enough about it to not let it die.

“Someone who worked for the chamber basically got some people together as a non-profit to join as a board of directors to make it continue. That’s the point where it might have just fallen by the wayside and been a thing of history had it not been for this group of people,” says Rankin.

“I think that the passion that the person had that started our non-profit was so strong that he was like, ‘We definitely can’t let anything happen to this.’

“At the end of the day when all the dust is settled, we aren’t making bank or anything, but we are providing the community with this event and our board’s mission is really to get people out recreating. So, we’re not really in it for the money, we’re in it for the community.”

While Ski to Sea got buy-in from the entire Whatcom County in the form of local business sponsors, more than 800 volunteers and government support, the same outcome wasn’t in the cards for Whistler’s race. Instead, everybody wanted a cut from an event that wasn’t in the businesses of making money in the first place.

“You’ve got insurance costs, you’ve got licensing, everybody wants a piece of the pie. That’s what I was finding towards the end,” says Walhovd.

“Here I am, I’ve got my hand out trying to get a free pair of goggles [as a prize] and then I turn around and here’s the municipality and they want to get ‘X’ amount of dollars off of me for a permit and then you got highways wanting a chunk out of you and just so many groups they had their hand out to me.

“Some people figured that I was making a lot of money off of it, but there was never any money in it.”

The race would live to see another day, however. In 2014, 23 years after the last edition of the original Great Snow Earth Water Race, the event returned as part of the Resort Municipality of Whistler’s Great Outdoors Festival (GO Fest), designed to signal the start of Whistler’s summer season and shift the focus back to a more family-friendly atmosphere after the local May long weekend, historically a magnet for young partiers from the Lower Mainland, had been struck by several incidents of violence in the years leading up to it.

According to Whistler Mayor Jack Crompton, while the new rendition of the race in 2014 and 2015 was viewed as a success, it proved to be too “logistically challenging to hold a race that took place across so many locations,” especially at a busy time of year like Victoria Day long weekend.

Unfortunately, the revamped race didn’t seem to have the same support or community buy-in that made it successful in the past. It had lost the essential element that made the original race so special.

“I think when you take the present day’s kind of more mass-planned, mass-organized types of races, it’s hard to have that no-rules mentality anymore and the spontaneity that the early ones had,” says Alyssa Bruijns, head archivist at the Whistler Museum.

“I think the [GO Fest] version of it felt too much like you could drop it anywhere, in any mountain town. But I think as well, there’s still a lot of events that have that spirit; it just might not be the Great Snow Earth Water Race anymore.”

For now, with no plans to bring it back, the Great Snow Earth Water Race will continue as a cherished memory of a distant and simpler time—and the subject of the lingering question: what would it have become if it had never been scrapped in the first place?