For decades, Whistler and Blackcomb mountains have loomed over the hearts and minds of skiers and boarders the world over. Yet these beloved twin peaks aren’t the only areas to host a commercial ski hill locally over the decades.

For a dozen years between 1969 and ’81, Whistler had another ski hill, situated in what is now the Rainbow subdivision, between Alpine and Emerald Estates.

When Ski Rainbow first opened to the public in 1969, it featured two lifts, a 121-metre rope tow for beginners and a larger 365-m rope tow, with about 60 m of vertical. With four runs, a day lodge offering snacks, and even night skiing (something Whistler Blackcomb still doesn’t offer), for just $3 ($24.67 in today’s dollars), you could ski from 9 a.m. to 10 p.m., five days a week. For $100 ($769 in 2023), you could take the entire family skiing for the season.

Norm Paterson owned the property, while Vic Christiansen managed it and the associated ski school. After several years in operation, Paterson, in 1978, sold the property to Tom Jarvis, who planned to develop the hill into a residential neighbourhood, changing the name from Ski Rainbow to Rainbow Ski Village.

“The reason we purchased the property was not necessarily to run a little old bunny hill, but we wanted to develop the property into lots and sell off lots over the years,” Jarvis says.

Unfortunately for Jarvis, the Resort Municipality of Whistler (RMOW) was focused on developing the Village Centre at the time, declining to move forward with the subdivision proposal.

“They wanted all the activity and all the onus and everything to be on the development of the new town centre that was coming down the road, so they wouldn’t give us any development rights,” he says. “But in the meantime, we decided to run the ski hill for a while to generate cash flow.”

As a means to draw extra revenue, Jarvis banked on his experience as a restaurateur, having previously run Whistler’s original Keg Steakhouse, and opened a restaurant at the ski hill that was named after his son, Beau. The restaurant was a success, becoming a favourite spot for visitors and locals alike at a time when Whistler had only a handful of restaurant options.

It even caught the attention of Canada’s “First Lady” Margaret Trudeau, then-wife to Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and mother to current PM, Justin Trudeau.

Jarvis recounted when Margaret came into the restaurant with a large group, without a reservation, including three RCMP detail officers. Not wanting to offend the regulars, the restaurant ended up turning her away, despite pleas from officials in Ottawa.

“She came in on a busy Saturday night, and she didn’t even get in,” Jarvis recalls. “She got to the front door, and our host said, ‘On Saturday nights, you can’t come in unless you have a reservation, and we just can’t let you in.’

“Then, about half an hour later, we got a phone call in the restaurant from somebody in Ottawa asking if we could make a special exception and trying to get her in somehow. She had heard a lot about our restaurant; it had a good reputation. We had great chefs; my chef was from France, Michelle Barclay was really good, and we just said, ‘No, sit in your car, and we’ll bring food out to your car. That’s all we can do.’ We couldn’t have turned away the regular customers. That’s not fair to them.”

As time went on, the cost to run the ski hill continued to grow. Labour, maintenance and electricity costs climbed (sound familiar?), as well as the costs to run the grooming machine, which Jarvis describes as having old army tractor wheels with old mattresses attached to groom the hill.

The hill was mostly popular on weekends, especially with beginner adults and children wanting to learn to ski. More advanced skiers tended to go with the more challenging terrain offered by Whistler Mountain, which continued to expand its ski infrastructure over the decade.

Beau Jarvis fondly remembers skiing Rainbow as a child, finding ways to slide down the slope at high speeds, taking jumps with friends—often into nearby groups of skiers, much to the chagrin of his mother, who would get on the loudspeaker to yell at him to stop fooling around.

Some of Beau’s fondest memories of the hill were at Christmas, when Santa Clause would visit Whistler.

“They used to do a thing at Christmas for all the kids. Santa would fly in on a helicopter, get out of the helicopter with his bag of toys, and start giving things to all the kids,” Beau says.

Faced with a money-losing operation, Tom Jarvis tried to get Paterson to take the hill back over, an offer he ultimately declined. With that, the difficult decision was made to close Rainbow Ski Village in 1981. Beau’s Restaurant continued to operate for a couple more years, while the family continued to push the RMOW for development rights. In 2007, three decades after Rainbow Ski Village closed down, the RMOW finally approved the Rainbow subdivision.

Around the time Rainbow Ski Village closed, a local Whisterite was designing a ski hill near Cold Lake, Alta. The timing worked out well for Jarvis, who wanted to get rid of the leftover equipment from the ski area. He sold it all to the new operation, for use by the Canadian Forces.

In proper Whistler fashion, the trove of equipment was picked up by the military—but not before a quick pint at The Boot and a performance of the infamous, scantily-clad “Boot Ballet” before heading to flatter ground.

“They would have on Thursday, Friday and Saturday nights a lot of rock bands that came to play, but they occasionally would have strippers,” Jarvis says.

“Somehow, they figured out what was going on in this place. So, they parked these flatbed trucks loaded with ski equipment, motors, rope tows, and whatnot, and went into the pub to have a few beers. People were driving by and saying, ‘What the hell is going on here?’ when you see all our stuff loaded on these trucks. They stopped for a few beers and watched the dancers and then kept on going to the [Canadian Forces] base out in Chilliwack.”

Why B.C. has lost so many ski hills

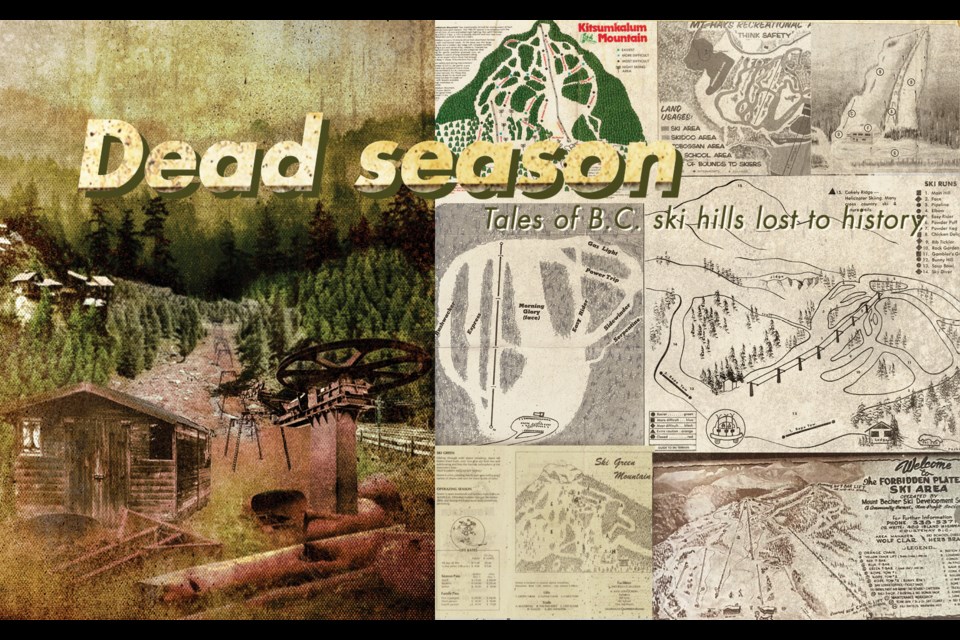

Rainbow Ski Village is just one of the more than 30 B.C. ski hills that have shut down over the last few decades, from small, community-run volunteer efforts built with little more than a single rope tow to larger destination resorts with dozens of staff.

Each hill ultimately closed for different reasons, from changing climates and conditions to rising costs and accidents such as fires or lift failures.

Mount Hays in Prince Rupert, for instance, had a gondola going to the top of the mountain overlooking the city and ocean below, with a T-bar connected to several runs and one heck of a view on a clear day. Unfortunately, it closed due to a fire that damaged the gondola system.

Vancouver Island’s original ski hill, Forbidden Plateau, which saw skiing begin in the 1920s when people would hike from the village of Bevan up to Mount Becher, suffered a slow death, likely beginning with the collapse, in 1999, of one-third of the day lodge roof under heavy snow. Uninsured at the time, the damage would cost roughly $250,000. Only a week after resuming operations, the ailing ski area suffered another disaster when a valve on its diesel tank broke and leaked more than 5,000 litres of fuel, contaminating a stream and the well water at nearby cabins.

Facing possible legal action from cabin owners, and the provincial government planning to recoup the costs of the fuel clean-up, Forbidden Plateau announced it was out of money and closed indefinitely.

A few smaller hills, like Grandview Acres or Lac Le Jeune Resort, just outside Kamloops, closed their skiing operations, but continued operating as non-winter destinations. Each of these hills had its own unique qualities and, for many people, are home to fond memories of learning to ski.

Some ski hills, meanwhile, failed not due to poor weather conditions or unfortunate accidents, but because the towns around them collapsed in the wake of declining resource pricing and major projects leaving for greener pastures.

The small towns of Cassier, Stewart, Mica Creek, and Bralorne, for example, had popular local ski areas that closed primarily due to residents leaving town altogether.

For many small community hills, such as Lytton’s so-called “Botanie Bump,” the cost to insure the hill skyrocketed, putting pressure on the volunteer-run organizations that operated them.

In the case of Lytton, the hill closed in 1987 after 18 years in operation.

Lytton Mayor Denise O’Connor was in Grade 2 when she moved to the town, and has fond memories of the one-run, rope-tow ski hill.

“They had a rope tow hooked to the back wheel of the [school] bus, and it went up to some pulley or whatever up the hill. And so, they went up and started the bus and put it into gear, and whatever gear they put it in was how fast the rope tow went,” O’Connor says.

The ski club set up a small teacherage nearby, which served as the local club’s lodge, storing ski equipment and serving hot dogs to hungry patrons. It was, on weekends at least, a gathering spot for the wider community.

“It was just packed, and everybody went up. Everybody. I can’t name anyone who didn’t go up,” O’Connor says.

Nothing remains of the old hill these days, with the teacherage having burned down, and the forest reclaiming the property. Sadly, many original pictures of the Botanie Bump were lost in the 2021 wildfire that devastated Lytton and claimed the local museum.

Challenges of a changing climate

Climate change has played a significant role in the closure of several smaller hills in B.C. Even just a few lousy snow years could spell financial disaster for these humble operations.

Pemberton’s community ski hill closed due to poor snow conditions and the growing popularity of Whistler. Operated by the local Lions Club on the Pemberton Benchlands, the slope had one gas-powered rope tow, bringing the community up a small, moderate-climb hill. The iffy conditions combined with the growth of nearby Whistler left little incentive to keep the hill going, resulting in it closing in the 1970s after only a couple of years in operation.

“Weather was a factor in the decision to close the ski hill. An inconsistent snowpack, the dreaded pineapple express, as well as small creeks coming down the runs were among the issues,” Pemberton area resident Allen McEwan shared on Facebook. “When conditions were good [in] 1971, many residents enjoyed the facility.”

Tillicum Valley Winterside Resort is another well-known, abandoned ski resort that attempted to ward off low-snow years. Located 15 minutes north of Vernon and half an hour away from SilverStar Mountain Resort, the Boyd family built the resort on their ranch property, eventually turning it into one of the most popular resorts in the Okanagan—and the first in B.C. to install snowmaking.

In 1965, Sandy and Molly Boyd didn’t have much money, but they had an idea to build a rope-tow hill for their five kids to use that ran off their tractor.

“It smelled terrible because he had to feed silage to the cows with that tractor before he went across the road and hooked it up to the rope,” Molly recounts. “So, it’s kind of stinky, but it was fun.”

Soon kids from around the neighbourhood joined in on the action, and the foundations of the resort began to take shape.

Eventually, the Boyds decided to move the lift to a different piece of land they owned in the valley with northern exposure. With the blessing of neighbouring SilverStar, they opened Tillicum Valley Winterside Ski Resort in 1969.

Fit with a rope tow and a T-bar on 750 metres of vertical, as well as a lodge, skating rink, toboggan hill and even night skiing, the resort was popular with beginners and families learning the sport (and adults taking advantage of a law at the time that let people drink on Sundays at resorts).

Whistler’s Rob Boyd, Olympian and first Canadian alpine skier to win a downhill World Cup on home soil—in his hometown of Whistler, no less—honed his skills slaloming at Tillicum.

“Rob developed excellent racing skills; he did a lot of training skiing down the T-bar. As people were riding up, he’d slalom around them,” sister Heather Boyd says. “I have people that I work with today up at SilverStar, they’ll say, ‘We’ll never forget that time I was riding the T-bar up there, and this kid coming down slalomed around all of us going up the T-bar,’ and I was like ‘Yeah, that was my brother.’”

At its peak, the ski resort employed 10 people, including lifties, ski instructors, and kitchen staff. Then in the early 1980s, an economic downturn combined with a series of dry winters hit the resort hard.

“Towards the end of the ’70s, we had not only an economic downturn but a downturn of snow. The weather warmed up, and it just wasn’t feasible; we couldn’t really operate,” Molly says. “You drive by it now on your way up to SilverStar, and you couldn’t have a ski hill there now because the snow [isn’t there]. Times have really changed as far as climate goes.”

Following these rough years, the resort went into receivership, and everything was sold off for 70 cents on the dollar. However, they managed to pay off all the debts without declaring bankruptcy.

Family patriarch Sandy Boyd eventually got offered a job at Whistler Mountain in the fall of 1981, and moved to the resort municipality, with the rest of the family following suit shortly afterwards.

Sandy’s experience with snowmaking proved to be a significant asset for Whistler, as he was the person that suggested creating a snowmaking system in 1984 to get the mountain open earlier than rival Blackcomb.

“That year, sure enough, they made enough snow to have skiing to the valley earlier that year, and that was also the year of the World Cup downhill in 1984. If it weren’t for that snowmaking, they wouldn’t have been able to run the race,” Rob says. “And it happened to be my first World Cup downhill race, too; if I couldn’t race, who knows what might have happened?”

Don’t call it a comeback

It’s hard to say if any the 30-plus closed and abandoned ski hills will ever come back to life. Tastes for the small, beginner-oriented ski hill have changed, and few family and community-run operations remain in the province.

Popular, larger resorts such as Big White, Sun Peaks, Revelstoke, and Whistler Blackcomb have become the primary destination for locals and tourists alike, making it harder for small ski areas to gain market share.

At many former ski areas, such as Ski Rainbow Village, Pemberton, Burke Mountain in Coquitlam, and Akloo in Cranbrook, housing developments have taken over the former ski properties, dissipating any hope of them returning to their former ski glory.

Of the hills that have closed over the years, a few have had proposals come up to bring them back to life. Among the most promising is Crystal Mountain in West Kelowna.

First opened in 1967 as Lost Mountain Ski Resort by Pat and Allan McLeod, for decades, the hill offered great powder on 30 groomed runs from its two chairlifts and a T-bar. However, tragedy struck the resort in 2014 when one of the chairlifts broke, injuring half a dozen people.

The resort has been closed since the accident, although some locals have been trying to get it reopened in full, or at least a smaller section of the former ski area. Given its proximity to Kelowna and relatively recent closure compared to other abandoned hills in the province, it seems a more realistic proposition than others.

Tabor Mountain Ski Resort is another recent closure that could reopen in the next few years. In 2018, following a fire that destroyed the resort’s lodge, it closed down. However, plans are underway to reopen it bigger and better than ever, with a dozen new ski runs and the number of mountain bike trails expanding from 15 to 40, along with a new lodge, rental shop and camping area. The province is currently reviewing this updated master plan.

Lac Le Jeune Ski Ranch could be another downhill resort that could make a comeback. For 45 years, from 1947 to 1992, the ski ranch, not far from Kamloops, operated a two-lift ski hill with nearly 60 km of cross-country trails.

In its heyday, the resort was fairly active for its size, typically bringing in close to 700 people on an average weekend.

In 1992, the resort’s aging T-bar needed to be replaced, but the costs at the time were untenable for the owner, and combined with growing competition from nearby Sun Peaks and Harper Mountain, they decided to close the slope for good.

This chapter of Lac Le Jeune’s history may not be where the story ends. New owners have since acquired the property and are considering rebuilding the skiing operation.

Jason Upton is the new Lac Le Jeune Resort operations manager, taking on the role at the beginning of 2023.

“I’m actually toying with the idea of opening the ski resort,” Upton says. “Although I don’t know if it’ll be feasible, I’m toying with the idea. I would like to see it done, but it has to make [financial] sense.”

While it might sound simple to reopen an abandoned ski hill on paper, practically all hills must undergo an in-depth review process that can take significant time, and requires approvals from the province and Technical Safety BC to ensure that lifts are safe and sound.

Looking ahead at the future of B.C.’s ski industry, it’s difficult to say if the list of lost ski hills will continue to grow over the next few decades. Many problems that hit those resorts continue to plague the wider ski world. With rising costs, a warming climate, and fewer young people getting into the sport, the next few years could be challenging for many ski areas, especially the smaller ones still dotting the province.

In Clearwater, the town’s little community ski hill couldn’t open this year due to insufficient snow early in the season. By the time snow came to the lower-elevation hill in February, the costs to reopen were too much for the small volunteer organization to handle, and the T-bar sat silent all season.

Insurance and lift-maintenance costs have also continued to rise, creating financial hurdles for some of the smaller areas. At Summit Lake Ski Hill, located 15 minutes south of Nakusp, liability insurance rose 33 per cent in just one year, putting heavy financial pressure on the volunteer ski club.

While both these hills continue to operate, with the local club in Clearwater hoping to be open all season long next year, the era of cheap ski days on tiny hills seems to be slowly ending.

Across the province, most of the ski hills that have survived and thrived have done so by expanding several times over. Revelstoke Mountain Resort is a perfect example: in 1983, Mount Mackenzie Ski Hill went bankrupt, and the city had to subsidize the small double chairlift operation. Fortunately for skiers, in the mid-2000s, investors decided to pour money into the resort and turned it into one of the province’s most popular and financially successful ski destinations.

Although little remains of the province’s lost ski hills, the memories they provided continue to live on. O’Connor will never forget breaking her first bone on the Lytton Ski Hill. Beau Jarvis won’t soon forget the day Santa flew down in a helicopter at Ski Rainbow. And the folks who skied Tillicum still remember getting used as practice slaloms by a future world cup champion. Gone, undoubtedly. But never forgotten.