For the sake of argument, let’s say you’re someone who enjoys sliding down snowy mountains. Should describe most of you. Doesn’t matter whether you do it on two boards, one board, free heel or fixed heel, just matters you like the rush of gravity and the small coefficient of friction between well-waxed boards and snow.

If, taking the argument a bit further, you like sliding down, say, Whistler or Blackcomb, it’s probably fair to guess you enjoy the free-flowing thrill of long runs. Varied terrain. Top to bottom. Non-stop. Good weather. Challenge weather.

Maybe you even like to slide fast, conditions permitting. Engage in a bit of friendly competition with your sliding buddies. Or just challenge yourself.

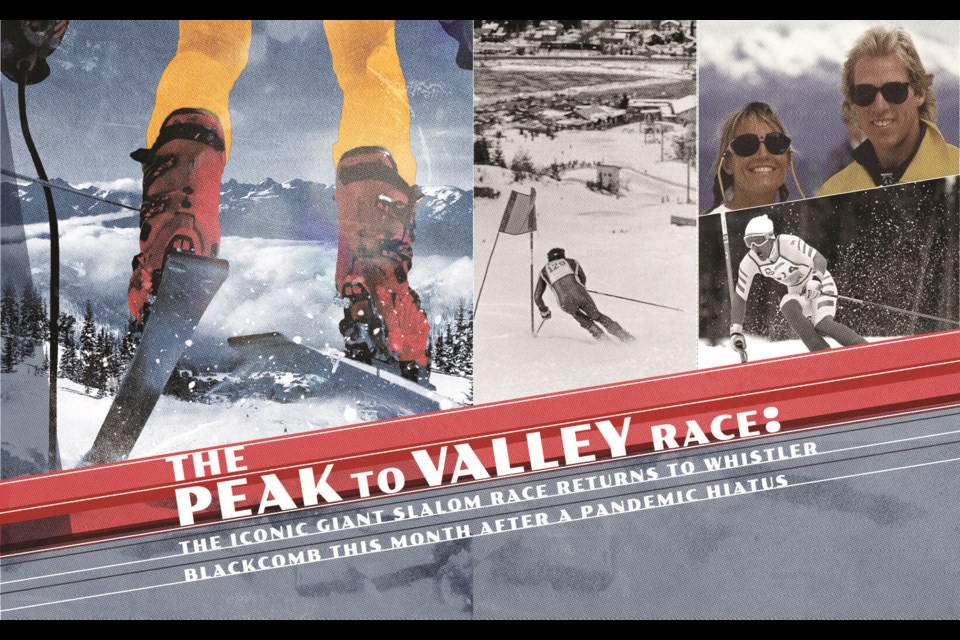

Those very thoughts, perhaps unconsciously, perhaps not, were going through Dave Murray’s head one day in the early 1980s. Crazy Canuck Dave and his loving wife, Stephanie Sloan, were standing atop Whistler Mountain. As Stephanie recalls it, “David and I used to ski top to bottom together. We loved doing it. It was a challenge. Our legs would burn and it was just pure fun. So, one day, standing on the peak, looking down at Creekside through the tips of our skis, we were thinking, wouldn’t it be great to have a race from top to bottom and set gates and make it exactly the way you’d ski it naturally… but throw in a little control so people wouldn’t kill themselves going straight?”

“Wouldn’t it be great?” Of course it would.

And thus was born, a few years later, Whistler’s Peak to Valley race, the longest—well almost—giant slalom race in the world.

OK, the Südtirol Gardenissima race at Val Gardena in Italy is, technically, longer—six kilometres as opposed to 5.6 km. But its vertical is just over 1,000 metres and they set somewhere in the neighbourhood of 110 to 115 gates. By comparison, the full Peak to Valley race drops around 1,385 m and frequently includes upwards of 180 gates. No offence, Val Gardena, but pffft, sounds a little light to me.

Of course, either race makes you wonder about the World Cup/Olympic races we all ooh and aah about. While the Peak to Valley runs, good weather or bad, on a course we all ski regularly, which is to say highly variable, World Cup races run on courses that have been fussed over like a Hollywood starlet’s makeup on Oscar night. Safety systems are so extensive, racers feel compelled to push the boundaries of human endurance, secure in the knowledge they may end a career but probably not a life. And with the men’s time usually under two minutes and women’s under a minute-and-a-half on a shorter course, well, it makes a guy wonder why they even bother holding them on big mountains. Yawn.

Consider Whistler Blackcomb’s real race history. In addition to the Peak to Valley, there’s a rich, historical lore of races. Like the largely underground Sextathalon—six skiing disciplines, including moguls and a gelandesprung, all skied on the same skis—and storied races like the Saudan Couloir. Whistler has a history of balls-to-the-wall ski racing that makes World Cup downhill seem like a debutante cotillion.

But there’s nothing like the Peak to Valley. And best of all, it’s back! After a COVID hiatus, the race is back for its 37th running this year, scheduled for Friday, Feb. 24 and Saturday, Feb. 25. Still time to get your teams together.

The Concept

Murray believed in racing as the gateway to both being a better skier and getting greater enjoyment from the sport. He also believed everyone should have a chance to race and have fun doing so. The Peak to Valley was envisioned as a citizen race, open to all, lots of fun.

So unlike, say, the World Cup, you can race in it. Me too. Anyone. Any age. The race is run by teams of four; two on Friday, the other two on Saturday. In the early days, to encourage older skiers to join in, one member of the team had to be over 35. As race fever caught on, that was dropped.

For most of its run, teams had to have at least one member of the opposite gender. Still do today. Teams are categorized according to their cumulative age and compete in age-bracketed groups. In 2020, the youngest category was 150 years and under, the oldest 250 years and up. Four members; you do the math.

Two favourite strategies for winning your category are including a ringer, generally a recently retired or still carded racer, or larding up with seniors who can still rip it up, there being no shortage of fast skiers in this town in their 70s, and even in their 80s. As a sidenote, the oldest Peak to Valley racer was 92 when he ran his last race! Racers run over two days—oldest racers go first, youngest last—and start 60 seconds apart. Passing is permitted and frequent.

While speed is always a good strategy, the single most important element of this race is simply finishing. It’s a tortoise-hare kind of thing. You can be blindly fast, but if you miss a single gate, your run and team is disqualified. No bragging rights; no glory.

But all is not lost. If you miss a gate—so many ways to do that—you can stop, make your way back uphill to a point above the gate you missed, go through it and keep on truckin’. Same if you fall. Your time won’t be great, but your team effort will still count. Glory of a sort but limited braggin’ rights.

Everybody and their spouses head up to the Roundhouse for a rip-roaring party on Saturday night—frequently a continuation of the party that started Thursday night—where the overall winners of the race are awarded the coveted Stephan Ples trophy and the winners of the oldest age category are awarded the even more coveted Dave Murray trophy, both of which were graciously donated by Fred Zeilberger, a Peak to Valley legend, to honour his two friends.

The Full Course

Notwithstanding its name, the race has only been run from Whistler’s peak once. One day. Never again. The problem is both the physical challenge of racing from the peak and the logistical challenge of setting a course through Whistler Bowl and keeping errant public sliders out of the way. Difficult but not impossible.

John Kindree, who has been one of the course setters since the beginning, was there on Feb. 5, 1988, the one and only day the race started from the peak. “We were up top by 6:30 that morning, punching gates in down Whistler Bowl. Dave was with us. But as outgoing as he was, we weren’t making much progress. We had to push him to stop talking to people—he was really outgoing—and keep setting gates,” he says.

June Southwell, who for years was the woman to beat, was lucky enough to be one of the people who started that Friday from the peak. “There were huge, massive ruts right from the start,” she remembers. “Dave Murray was there, like he always was, to send people on their way. It was just so cool and at the same time so terrifying because it was so rutted. Huge, monstrous ruts. And there’s Dave at the top and Dave’s primary focus was always safety and people having fun. The poor guy would tell every person, ‘Just take it easy.’ That’s all he wanted. It was always about finishing and being safe.”

Not everyone that day found it safe. Who remembers poor Miss Japan? Well, no one remembers who thought it would be a cool idea to have petite Miss Japan be a forerunner that day. At least no one’s owning up to it. Bob Dufour remembers what happened though. “She was in a pink ski suit. A very pink ski suit. She was very small, very delicate. A tiny, beautiful Japanese woman. She, well, she tumbled… down… all the way down. Pretty much from the top of Whistler Bowl to Shale Slope. It was pretty sad… watching that little pink suit just tumbling, tumbling.”

So, the starting line changed. The name didn’t.

Weather is always the wildcard. There have been years where the course has been greatly shortened by bad weather. Like, bad enough to close the rest of the mountain to the public. More on that later.

But on a reasonable year, the course runs from below the entrance to the Saddle, in Glacier Bowl, scoots along the reservoir, down Old Man, Upper Franz, Lower Franz and ends within a beer bottle throw of Dusty’s, 5.6 kilometres of quad-destroying, non-stop fun.

The Records

The best time ever posted in a full Peak to Valley race—faster times having been posted over shorter courses—was 4:52:03. That is not a typo; four minutes, 52 seconds, and three one-hundredths of a second. The year was 2000. The course was “as good as it gets,” as Kindree recalls. “We’d had perfect conditions for probably a week: sunny, cold. When we set the course, it was clear weather and cold, fast snow top to bottom. We hardly needed grooming even at the bottom. We just slipped things out as the race progressed.”

By contrast, the slowest time ever recorded in the race was 34:32:11 in 2006, over half an hour to cover the same distance. Well, it’s just that kind of race and a record is a record.

Chris Kent enjoys the distinction of holding the first record. I could tell you what it’s like to ski the course, but Kent can tell you what it’s like to ski the course and win.

“I divide the course into three sections,” he explains.

The first section is from the starting line to the bottom of Old Man. The challenge is to ski fast off the steep pitches and carry your speed onto the flats. It’s tricky. You have to mentally ski the right line. Not go too straight but really race it. In ski racing, it’s a sin to rest your elbows on your knees in a tuck, but in this race, that’s what you try to do so you can actually rest and still be in aerodynamic position.

“Coming off the first section, you’re gliding across the flats before Upper Franz and you’re beginning to really feel your legs. The first time I ran it, about there I was thinking, ‘Oh my God, how can I possibly finish this course?’ This is where you have to start getting tough,” Kent says.

“Going into the first pitch down Upper Franz’s, the course really changes. It gets narrow (not quite half the width of the run is fenced off and open to the public) and steep and the snow texture changes. There’s probably been some melting and freezing and you can get almost anything through there. If there are deep ruts, they seem that much deeper. You have to be right on it. As someone who’s trying to win the race, I go into that section and try and carve for as long as my legs will let me. I find if I can carve several gates past the point where Highway 86 enters Franz’s before I lose it so badly I have to start sliding, then I’m usually going to have a good race.

“Past Highway 86, my legs begin to turn to jelly. I begin to slide my turns because I’ve got nothing left. It feels awful to be sliding through there, losing speed. I get angry and carve a couple of turns, pick up speed and then have to slide a few. Carve, slide, carve, slide. What I’m really keying on at this point is to hold my line so I can carve off the last pitch.

“In the final section, Lower Franz’s is flatter and rolling and widens up. You’re carrying a little more speed through there. The gates are always set so you can carve ‘em, but you really have to dig deep and stay low. By now, I’ve said ‘no way’ about 10 times. Then, finally, you come into the last pitch and can see the finish line. You try to let your skis run and try not to ski so straight you ski off the course. But when your legs are that tired, it’s easy to do if you take too straight a line. Keep focused a couple of gates ahead. Keep your head from bobbing. Keep your legs in powerful position and look ahead. Oh yeah—and breathe.”

The astute reader will have noticed it took longer to read Kent’s description than it actually took him to cover the distance he’s describing.

The Shortened Course

Anyone who’s skied here more than a day or two brutally understands the local version of Mark Twain’s quip about New England’s weather: “If you don’t like it, wait a few minutes.”

Historically, weather has been a factor in the Peak to Valley. The official race log for 1991 lists Friday’s weather as “YUCK.” That’s not so bad considering Saturday’s weather was entered as “DOUBLE YUCK.” Yet, even in adversity, or perhaps especially in adversity, there lies mythology.

“YP (Peter Young, longtime former events manager for Whistler Blackcomb) called me around 3 o’clock in the morning on Saturday,” recalls Dufour about that year’s race. “The groomers had called him and told him conditions on the mountain were insane. YP said we were going to have to cancel the race. We’d never cancelled the race before and even though it was only a few years into its history, it was already a fixture.”

He continues, “I called the groomers and told them we just had to run the race that day and to do the best they could to groom the course. We ended up closing the rest of the mountain to the public, but we kept the Gondola and the Olive and Orange chairs running. (Historical note: That’s the original, four-passenger gondola out of Creekside and the two subsequent chairs that took people to the top of the Dave Murray Downhill, neither of which still exist.} We had to close the Orange after a while though and ran the racers up to the start (foreshortened to the top of Franz’s) with snowcats.”

Cate Webster, Queen of the Peak to Valley for years and in the eyes of many, a true sorceress for pulling it off each and every race, picks the story up. “The first day was horrible. The mountain was so stormy we went to the top of the T-bar to set up and when we brought the start tent out of the trailer the wind lifted it and we found it in June. In Harmony Bowl! We couldn’t even use the alternate start at the top of Old Man. It was raining in the valley, windy and snowing higher up.

“The second day, they closed the mountain. I’m on the radio with [Dufour] telling him he can’t close the mountain, we have a race today and a party tonight and we have to crown some winners. We end up running the Olive Chair and get the snowcats to pick people up at the top and drive them to the start of the course.

“In the midst of all this craziness, one of the competitors decides he’ll just walk up from the chair to the top of the course. Simon Wirutene was a skier on the New Zealand National Ski Team and he knew he was the last racer of the day. So, he walks up Franz’s, watching all the racers go by, gets to the top, steps into the start gate, clicks into his bindings and cracks off the fastest time of the day. He’s our Maori legend.”

The Dynasties

The Peak to Valley was an overnight success. It captured the spirit of the times and, more importantly, the spirit of the mountain, Whistler, and the man, Dave Murray. It also spawned other legends, including what would become two of the longest-running team dynasties in the race’s 36-year history.

The 1985 race was won by a team called Frankie Goes to the Valley, reputedly named after the band Frankie Goes to Hollywood. The team consisted of Sue Boyd, who clocked the fastest time of any woman that year, 6:14:23—exactly 20 seconds off Kindree’s fastest men’s time—Bob Boyer and the two men who would prove to be the team’s enduring nucleus: Julien Soltendieck and Shawn Hughes.

Frankie raced as a team, with a few personnel changes—most notably the acquisition of the lightning-fast June Brandon, later Southwell, who had raced with the B.C. provincial ski team—for 16 years. In 11 of those races, they won their age category. In 1985, ’86, ’88 and ’92, they won the whole race. Aside from a disqualification in 1993, the team never finished lower than eighth place, a remarkable feat considering for many of those years they were granting a substantial age handicap to the winners and at least some of them were reputed to be fuelled by substances better left unmentioned, but generally not considered performance-enhancing. Their accomplishment is all the more remarkable considering the team lacked what were generally regarded as ringers.

The team roster boasted more than a few well-known names around the valley for a year here, a year there. Rob Denham, Eric Pehota, Dean Moffit, Renata Scheib and Kelly Nylander all made appearances. And in 1993, Bob Switzer, who terrorized his age group in most any race he ran and who unfortunately left us last year for that racecourse in the sky, became a permanent fixture.

As noteworthy as Frankie, and perhaps even more in keeping with the race’s spirit of embracing all comers, was another team cobbled together that first year. Qualifying in an older cumulative age category, Beauty and the Beast never won the race. What they did though was dominate their class. For 10 years, with the exception of a single second-place finish, Bob Dufour, Kurt Karka, Fred Zeilberger and, most frequently, Leanne Dufour simply kicked butt.

Bob, who was director of the ski school in the early ’70s and mountain manager until his retirement, explained the genesis of the team. “In Austria, being ski school director is like being a ski god. I became very welcome with the local Austrians. We’d ski all day and hang out in the parking lot drinking schnapps in the afternoon. I just became one of the crowd. When the Peak to Valley started, I thought it would be a great event to get into so a couple of us got together and formed a pretty consistent team.”

Bob last skied with the team in 1994. His timing was impeccable. The next year, Zeilberger was disqualified and that was the end of the dynasty. “We couldn’t accept defeat,” was Bob’s explanation.

The race has spawned other dynasties that cobbled teams together and consistently finished high in the standings... or at least had a rollicking good time, both accomplishments being at the heart and soul of the Peak to Valley. And there have been teams since—Barry and the Rooster, Blue Ice Wrecking Crew, NZ Foundation Team among them—which have consistently placed high both in their age categories and in the overall standings and with some longevity may be the focus of future storytellers.

The Finish Line

As storied as the Peak to Valley is, it won’t last if it becomes a historical cliché. A good argument can be made that local interest in ski racing is experiencing a sharp decline notwithstanding skiing itself has somehow caught fire once again. While tens of thousands of spectators might crowd the finish of a European World Cup race, North American interests have tended to be drawn to more spectator-friendly events such as skier/boarder cross and freestyle. It has also been a while since Canadian skiers captured the imagination of even recreational skiers.

Still, the spirit of Dave Murray and his hope the race would be one for all ages and all levels of seriousness clings stubbornly to life. “It’s maintained a comfortable balance between competition and just getting out there and doing it and having fun,” Webster observes. “The party still goes off, people are still dancing. It’s maintained that special feeling.”

Bob Dufour adds, “The Peak to Valley’s a very important race. When you look at Whistler Mountain, the length, the vertical, the variety, the uniqueness of Creekside, this is an incredible tradition. You’ve got racers who have been in it for decades. As this place has developed, we find we’re often losing touch with the old traditions, the old-time Whistler. But during Peak to Valley weekend, you can get that feeling back, no matter how modern this place gets. The memories come out that week.

“Whistler’s changed a lot but in the Peak to Valley race, once you’ve crossed the finish line, you stop to talk to your buddies and realize this hasn’t changed one bit. For those who’ve been here for a long time, that’s important. And for those [competing in the race for the first time], to see that energy and enthusiasm, it just seems to be catchy. For us, keeping that tradition alive, remembering where we came from, is important.”

In a town that often either ignores or is ignorant of its history, hope springs eternal.

This is an updated version of a feature G.D. Maxwell wrote in 2014. Read it at piquenewsmagazine.com/cover-stories/a-whistler-tradition-2495452.