On Dec. 14, 2024, a fish farm off Vancouver Island was transferring fuel from a barge when something went wrong.

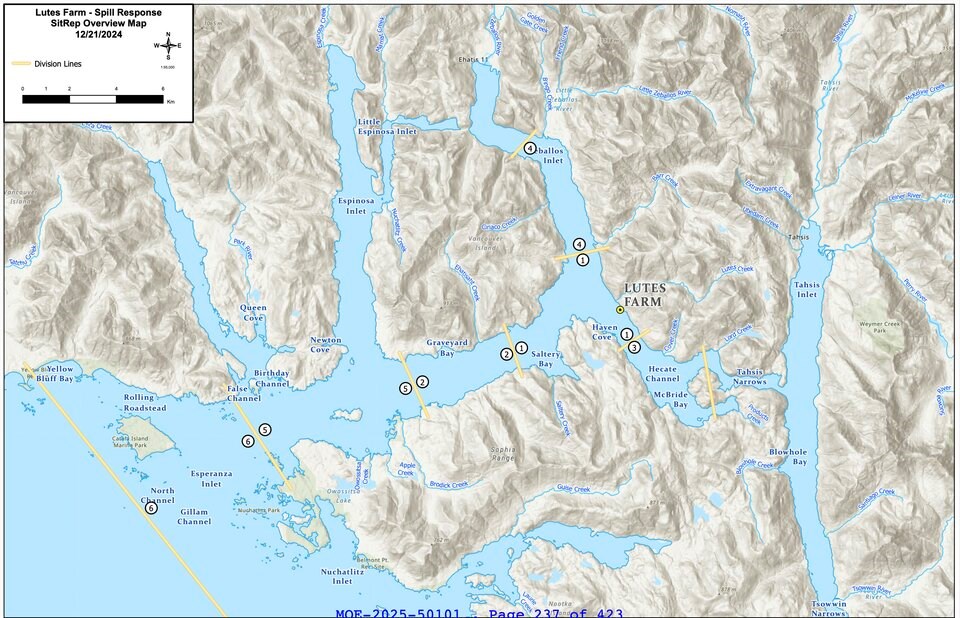

By morning, an estimated 8,000 litres of diesel had spilled into Zeballos Inlet.

Over the coming days, aircraft and boats scrambled to assess the spread of the fuel — all under a polluter-pays model overseen through a unified command co-led by the fish farm’s owner, Grieg Seafood.

But more than three weeks later, testing that should have taken place had been delayed, according to records released through a federal access to information request.

Critics say the incident raises questions about the role played by companies in responding to their own pollution, and whether the whole system is ready to handle a major oil spill.

On Jan. 8, 2025, D’Arcy Sego — emergency planning analyst for the Ministry of Environment’s Environmental Emergency Program — wrote in an email to a federal counterpart that Grieg Seafood expressed a “sudden lack of urgency” after cancelling plans to test the waters around the spill.

Work had been suddenly cancelled by the company without explanation, despite the province and federal government approving it, he said.

“Delaying sampling by another two weeks will likely show no impacts, which raises the question: why would we prioritize sampling quickly for other spills if waiting is an option?” wrote Sego.

In an email to BIV, a spokesperson for B.C.’s Ministry of Environment and Parks blamed the delay on “extensive edits” required by the federal government to an environmental sampling plan, which includes shorelines, animals and plants. (Records of official correspondence show provincial officials blaming the company — not the federal government — for the delay.)

The spokesperson told BIV that the delay prevented officials from getting a snapshot of the spill, but denied it delayed the reopening of fisheries or affected the government’s ability to obtain a final assessment of the incident’s overall impacts.

The province was “encouraging sampling to occur as soon as possible” to inform local First Nations about the safety of marine food sources, according to the ministry.

Nuchatlaht First Nation biologist Roger Dunlop, who was on the water and shorelines during the spill response, said the whole process was fundamentally flawed.

He conducted his own testing and claims that the baseline reference samples used to measure the spill’s impact were taken from already contaminated areas, not pristine parts of the coast, as they should have been.

Dunlop’s analysis showed that the baseline sites chosen by the spill response’s unified command contained nearly 10 times more oil contamination than what he found in his own samples.

The sampling decision, he argues, made the spill’s actual environmental impact appear far less severe than it truly was.

The area around the spill is home to several salmon-spawning streams and herring-spawning sites, and offers fishing grounds for Great Blue Heron colonies and threatened marbled murrelet populations during their breeding season.

At one point, Dunlop said, Grieg directed him and others not to touch any dead animals, orders he said would have prevented proper sampling from occurring.

No large animals were reported to have died due to the spill. But after the spill, Dunlop observed a sharp decline in the sea otter population near Nuchatlitz Provincial Park, which is located at the mouth of the contaminated inlet, he said.

He noted that the number of otters “rafting” — or congregating in groups on the water — fell from approximately 800 to just “a couple hundred.”

In the event of an oil or gas spill, B.C. law requires polluters to restore any damage caused to the environment and take steps to assess a spill’s long-term impacts.

A spokesperson for the Environment Ministry said the incident “reinforced key practices that have informed subsequent responses,” while underscoring “the critical importance of deploying provincial staff to the site early during a large-scale spill event.”

But for Dunlop, the incident raises concerns about a provincial spill-response system that puts a degree of oversight into the hands of the polluting company.

“Their objective is to have minimum liability,” he said. “So they’re calling the shots. They write the contract with that biologist… And they didn’t want to pay more to sample more distantly to find some pristine sites.

“It was absolutely wrong for the industry, whose objective is to cover their ass, to be in charge of an environmental response where they’re trying to minimize their liability.

“They’re not looking out for the best interests of the environment and the people — they’re just looking after their bank account.”

‘We have done everything to minimize damage’

Jeanette Galtung Døsvig, a communications manager at Grieg Seafood, denied Grieg had a conflict of interest during the spill response.

“Our only goal was to determine and minimize the impact from the spill, then determine when [the] food source was safe for human consumption,” she wrote in an email.

Døsvig blamed the sampling delay on the Christmas break, when operations were shut for two days, as well as on last-minute questions from the government about its sampling plan that the company didn’t have time to answer before the low-tide window.

Døsvig said all parties — including First Nations — signed off on the sampling plans and where reference testing sites should be.

“At no point was there noted any animals in distress,” she added. “All through this we have done everything in our capability to minimize damage.”

(Dunlop acknowledged that the sites were agreed to by First Nations, but says later sampling showed they were a poor choice.)

A human-health risk assessment carried out by Health Canada’s Bureau of Chemical Safety ultimately found that consumption of shellfish in the spill area would not result in risk to human health.

But for six months, the spill prevented local shellfish harvesters from accessing oysters, clams and other species important to local First Nations, putting pressure on food sources and the local economy.

“There’s probably, like, 50 licences at least. And those guys can make a thousand bucks a night digging,” said Dunlop.

Records also suggest the spill response was at times plagued by miscommunication. Emails from an official at Strathcona Regional District show the regional body, and the Village of Tahsis, felt at one point like they were being shut out of decision-making, despite requests to be included.

The regional district declined to comment, and the ministry said it did everything in its power to share information with the local and regional governments.

In July, Grieg Seafood ASA announced it had signed an agreement to sell its businesses in Canada and Finnmark, Norway, to global fish-farming company Cermaq Group AS for US$990 million. The sale marks Grieg’s exit from Canada, where the salmon-farming industry has been grappling with the federal government’s plan to phase out open-net-pen salmon farms by 2029.

Polluter-pay model problematic

A Canadian official who worked in the incident command structure said the Zeballos spill was a once-a-year event big enough to raise concerns.

The official, who spoke on background because he was not authorized to speak to the media, said the timing of the spill — including the holiday season and missed tidal windows — contributed to the delayed response.

He acknowledged that systematic observations from ships and aircraft could have been better and would have helped response teams learn where the diesel went.

And while the official said Grieg Seafood appeared to act in “good faith,” it was working under a polluter-pay model that has repeatedly come up as problematic.

Without a polluting company’s high-level involvement — a joint-command role companies don’t get on Canada’s East Coast, where the government is more clearly in charge — the government might make other decisions to test farther afield or take more of a precautionary approach, said the official.

“You don’t have the person flicking the cigarette butt in the forest telling firefighters and helicopters where to go,” he said.

Such delays would be a lot more consequential in a big spill, but the federal government could also bring a lot more resources to bear in an emergency, said the official.

That includes federal laboratories that could expedite sampling and likely would have helped speed up the spill response off Vancouver Island.

In the worst-case scenarios, the federal government does have the ability — though it has never exercised it — to take over a spill response.

“Where this could really bite is if we have a large shipping company that is very well versed and has good lawyers — this turns into a different game,” the official said.

“If there’s a tanker going aground, and we’re seeing a spill of 50,000 litres of bunker fuel — sticks to rocks, sticks to animals, doesn’t evaporate — we don’t even know how to deal with it… nobody does.”