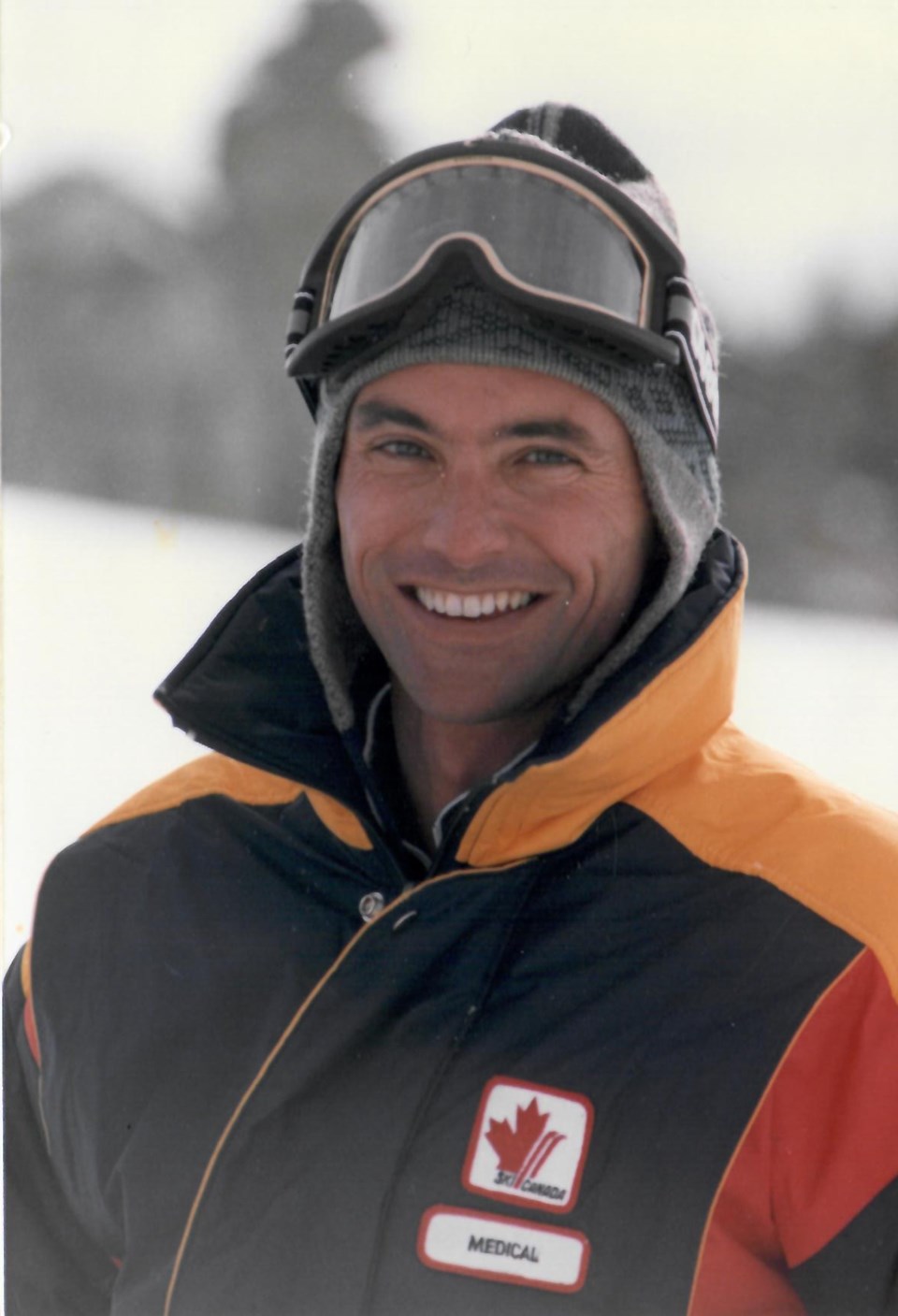

In many ways, Dr. Rob Burgess defied the stereotypical image of a family physician. He was an avid rock fan who attended Woodstock, a daredevil skier with a need for speed, and a prankster with a bone-dry sense of humour, but when the call came to help his community, whether in-valley or on-mountain, you couldn’t ask for better care.

“His work ethic was really something. There was no question he was there for everyone. He’d throw the pager down the hallway when somebody would call him, and he would leave the house slamming doors, but he’d get home, and I would ask him if he was OK, and he’d look at me and go, ‘Yeah, why wouldn’t I be?’” remembered wife Jan. “He never ever thought twice about going to see somebody at all hours of the night, for anything.”

The long-time local physician, chief medical officer, Whistler Medical Clinic co-founder, youth hockey coach and ski patroller died at his Whistler home Sept. 14 following a short battle with cancer. He was 71, and leaves behind his wife, son Johnny and daughter Micky.

A precocious medical student, Burgess had been challenging expectations from a young age, said best friend Dr. Bill Akeroyd, who attended the University of Toronto with Burgess in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s.

“I think a lot of the professors initially had a hard time warming up to him because a lot of them were kind of old-school, and with his really long hair and outfits that he wore, they were thinking he was kind of a wacko. But because he was so smart, they warmed up to him,” he said.

Following graduation, Akeroyd convinced Burgess to join him on a short stint in Banff, a time that led them both to realize “we weren’t going to spend our lives in Ontario,” he said.

Wanting to be closer to the mountains, they spent their residency at Vancouver’s St. Paul’s Hospital, a period when Burgess first familiarized himself with Whistler, which was then a sleepy ski town of a few hundred people.

Eventually Burgess made the move to the community full-time and established Whistler’s first 24-7, on-call doctor service. He also joined the ski patrol as Whistler Mountain’s in-house doctor—in part to cover the bills when the medical business here wasn’t exactly booming—establishing many of the health and safety protocols that are still in place today, said Roger McCarthy, the former director of safety and lift operations for Whistler Mountain who hired Burgess in 1978.

“I worked in ski areas all over the world and … in all those places, he’s an icon. For me, he was the standard by which others were measured,” McCarthy said.

“He carried this community in a white coat for over 40 years.”

For many years, Burgess was the only game in town, and he perfectly exemplified the ethos of the old-school country doctor. Between his job on-mountain and the valley clinic he established—not to mention side gigs as a heli-ski guide and the national ski team doctor—it wasn’t unheard of for him to work 35 hours straight. If a baby was being born, he got the call. If there was an accident on the highway, he got the call. If he attended a ski injury on the mountain, he was usually the first one there, like the time a helicopter whisked him to the peak of Whistler to treat a women with two broken legs, only to find himself in waist-deep powder, still sporting his dress shoes and slacks.

“I would guarantee he never did a 9-to-5,” McCarthy said. “The coverage he provided was extraordinary.”

With the well-being of an entire town resting on his shoulders, Burgess made sure to take whatever moments he could to enjoy himself. A prolific practical joker, McCarthy recalled a time he was leading a tense meeting with the patrol team when Burgess began blaring Frank Zappa from the bump room nearby.

“So I’m having a meeting with the patrol and we’re trying to get them straightened out, and all of a sudden this record pipes up, ‘You’re an asshole! You’re an asshole!’” McCarthy remembered with a laugh. “Of course, all the rest of the guys knew exactly what was going to happen. It was a big joke and it went on and on.”

But there’s no denying Burgess took his role as a family physician seriously. He regularly went out of his way to mentor young doctors, like 2021 Citizen of the Year Dr. Karin Kausky, who began working at the Whistler Medical Clinic in ’93 when it was still housed in an old Atco trailer.

“He was very generous about mentoring people, about helping them figure out how to work in an environment that was pretty unique when I started here,” said Kausky. “He really was the pioneer of family practice in Whistler. He did whatever it took.”

Serving as a physician in Whistler for 43 years, it’s clear Burgess leaves an enormous legacy behind, one that will carry on through a fund set up in his name by the Whistler Health Care Foundation, which will support primary care initiatives in the Sea to Sky corridor. Donate at whistlerhealthcarefoundation.org/make-a-donation.

“I just think he would be so proud as it reflects how much of a pioneer he was,” Kausky said. “This carries forward the legacy of his commitment to full-service family practice, that longitudinal, relationship-based, cradle-to-grave care. I think it’s beautiful.”